New book recalls lost era of heroic boatmen

Saturday 18 December 2021 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in

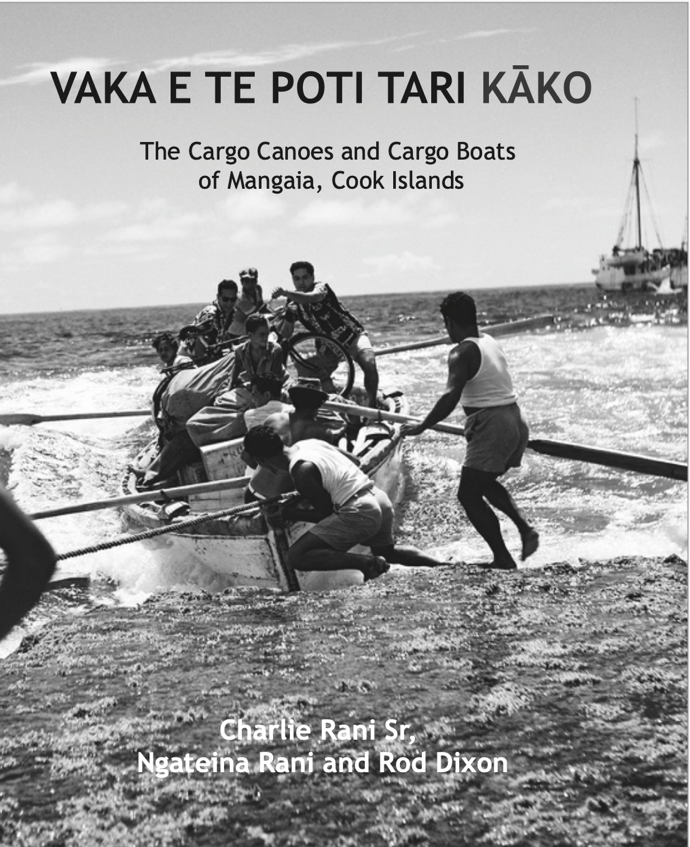

A new book recalls the lost era of surf boat lighterage on Mangaia, bringing it to life through the memories of one of the boatmen and visually through 150 historic photos.

Until the opening of its airport in 1977, the only way in or out of Mangaia – it’s lifeline to the world – was across an extremely treacherous reef. Passages through the reef were narrow, shallow, and none reached the full distance from beach to reef’s edge.

As a result, reaching the sea in a canoe required considerable effort.

An observer described the process of launching a large canoe at Mangaia in the late 19th century as follows – “Two natural ropes of immense length, composed of strong vines knotted together, were employed to drag her (the vaka) over the reef; one was pulled by women, the other by men. The islanders accompanied the vessel out to sea until she was clear of the reef, swimming with their feet and pulling the ropes with their hands” (Bradford Observer, 2 October, 1875).

The fact that women played an equal part in this process is interesting, given that boat handling has traditionally been considered a male preserve. But there is evidence that Mangaian women were equally or sometimes more adept at boat handling. Maki, one of the island’s early missionaries to New Guinea, was noted for her extraordinary boat handling skills and “ability to steer a boat through the boiling surf with perfect safety”.

Nevertheless, it was men who predominated in twentieth century lighterage - as oarsman, tu’oe (steersmen) and tu’ava (experts who directed canoes in and out of the reef passages).

These men are the subject of a new book – Vaka E Te Poti Tari Kako – a dual language text in Cook Islands Maori and English, written by the late Charlie Rani Senior, who as a young man worked on his father’s flat bottomed lighter, and translated by his son Ngateina Rani. The book has an introduction and additional chapters on canoe companies, canoe-men’s unions, reef passages and accounts of “shooting the reef” by Rod Dixon.

In his chapters, Charlie Rani Sr describes the process of construction of cargo canoes, the native woods they were made of, the various adzes used in their construction, the ceremonies attending canoe building, the vaka crews, the organisation of boat day, etc.

He recalls boat day mornings, when the large poti papa were dragged over rocks to the beach – “A rope of about 5 maro (30 feet) was tied to a post on the bow. Some men held the rope while others held the hull, dragging the boat towards the sea. Wooden rollers were put under the hull, making it easy to slide the boat into the water. All this activity was accompanied by a tapatapa or chant to help people pull together in unison - ‘ē reti ē, ē reti ē’ (heave ho). If the boat came to halt, the person calling the tapatapa would call again – ‘ē reti ē, ē reti ē’. This would provoke the response from the people pushing - ’Ua ngao. (Big balls). Then everyone would laugh.”

Rani describes the introduction to Mangaia, in 1941, of the flat bottom boat or poti papa, by Teao from Ma’uke and Enoka, an SDA pastor from Manihiki. The designs of these boats were later elaborated by Reverend Bill Marsters when Marsters was Orometua at Oneroa, Mangaia, using his own knowledge of Palmerston’s plank built boats.

While the smaller cargo canoes had been owned and operated by individual kopu tangata, the large poti papa required a greater number of oarsmen and a larger shore crew. This led to the creation of puna boat companies or kamupani – the members of each kamupani sharing the workload on boat day and a commensurate share of the boat’s profits. And profits could be large. On a good day Mangaian boatmen could load 150,000 cases of fruit and unload 120 tons of cargo (at £4 per ton) during a single ship visit of 7.5 hours.

Local ship’s captain Don Silk recalls the intense competition between puna boats to reach the ships and claim a section of cargo for lightering – “Sometimes they would meet us miles out at sea at daylight, and the crews would fight to get the cargo out of the ship, for they were paid by the ton and each lighter was owned by a separate village.”

Rani writes that, “When the ship’s hatch was opened, the canoe-men scrambled to sit on a section of the cargo and claim everything beneath them to the bottom of the hold, for their boat or canoe. The idea was to ensure that some of the cargo on the ship was allocated to each boat for trans-shipment to shore.”

Initially exploited by European traders, Mangaian boatmen realised the real value of their labour while serving as boatmen in the Middle East during the first world war. British Army officials regarded their boat handling skills as vastly superior to those of European and local counterparts. It was said that “thirty islanders could do the work of 170 British soldiers”.

According to Howard Weddell “their speed and prowess in running surf boats from supply ships in Egypt led to threats of strike action by local labourers, put out of work” by the stronger and more efficient islanders.

On their return from the war, Mangaian canoe men formed a union and raised the tariff for loading and unloading cargo from £1 per ton to £3.10 per ton with plans to raise it to £5 per ton. These plans were thwarted when the New Zealand Administration introduced the Mangaia Ordinance 1922 No 4, legally fixing lightering tariffs at very low and unrewarding rates.

Mangaian boatmen were well known for using their important role in linking ship to shore to frustrate unpopular policies, politicians and officials. When orange gassing was imposed on a reluctant island by the New Zealand Administration, the gassing equipment was ‘lost’ overboard en route from ship to shore. Building materials for an unpopular fruit control project met a similar watery fate. And unpopular politicians and colonial officials often received a salutary soaking even in the calmest of seas.

By the 1960s, Mangaia had a new passage and harbour, thanks to the efforts of the then Director of Public Works, Win Ryan, plus a stock of discarded World War II bombs delivered by the NZ navy, and the combined efforts of George and Alec Tuara who received 3 pence a day danger money to lay the bombs, light their fuses and run. The following decade saw the introduction of steel barges constructed by Ross Hunter, replacing forever the poti papa and cargo canoes. An era had come to an end.

This new book records that lost era, bringing it to life in Rani’s memories, augmented by the recollections of surviving boatmen and visually with 150 historic photos covering the years 1890 to the late 1970s.

Published by the Mangaia Historical and Cultural Society, a limited number of copies are available from the Cook Islands Library and Museum Society, Takamoa.