Karioi – the pleasure months

Saturday 2 December 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Memory Lane

Tests of strength formed part of the karioi entertainment. 23120112

There was a time when Cook Islanders lived and worked in closer harmony with the seasons and enjoyed significantly more leisure time. Summer holidays lasted several months during which young people dedicated themselves to pleasure. By Rod Dixon.

Tumatuma te pau e, tei Itikau e,

Tei Itikau na Paoa

Ko te ninga ia o te karioi

Softy sounds the drum at Itikau

The famed drum of Paoa

It is the gathering of young men

In the southern Cook Islands Maori calendar, the rising of Matariki in mid-November signalled the commencement of the new year, followed by several months “of heat, rain and plenty”. For young people, this was the time of the karioi (or kariei).

The word karioi, (kariei, ka’ioi, ‘arioi, etc) is associated with being idle and devoted to sensual amusement. But in the pre-Christian era, ‘karioi’ referred to a prolonged period of months during which the seasonal abundance of food allowed Cook Islanders to relax and refresh themselves before re-starting the annual cycle of labour on land and sea. Beaglehole, speaking of Pukapuka, refers to these as the “pleasure months” (Ethnology of Pukapuka, 370).

On Rarotonga, the early missionary the Reverend John Williams observed that, “A number of young men used to unite in November and December, which is the spring of the year, and build a large house. When finished, they would go and fetch all the fine young women they could hear of, from all parts of the Island. These with all the young men would leave their fathers’ houses and take up their abode during the summer months while breadfruit and other fruits of the earth were abundant” (Williams, 1984; 262).

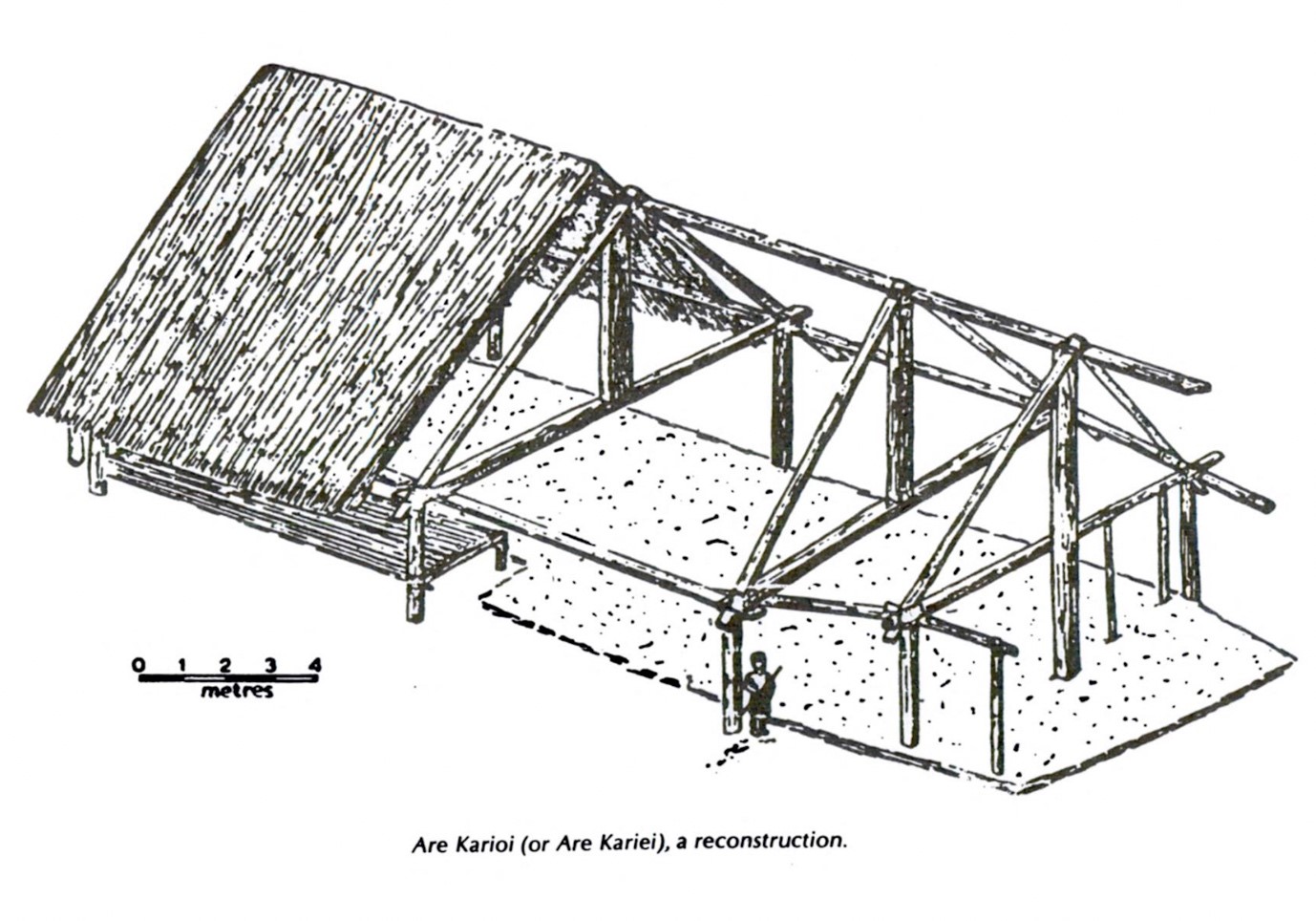

Stephen Savage writes that this large village house, built by the young men – Savage calls it the ‘are kariei– was “a house that was in olden days specially built and set aside for holding dances and other tribal amusements ... It was a place wherein great revelry was held, where all ceremonial dances were first rehearsed” (Savage 2012; 91).

John Williams (1984: 262) describes the ‘Karei’ as a house “full of young beautiful people of both sexes and music, dancing and festivity is perpetual or, in other words, the Karei exists in perfection” ‘Young’ has a different meaning for men and women. According to William Wyatt Gill, in those days, “a girl may be considered mature at the age of 14.” Men in contrast were considered ‘young’ until 30 and continued to attend the ‘are karioi to that age. William’s use of the words ‘perpetual’ and ‘perfection’ point to the belief then that what happened in the ‘are karioi was the closest human-kind came to Paradise.

Are Karioi or a house “full of young beautiful people of both sexes and music, dancing and festivity”. SUPPLIED/23120114

According to John Williams, “There were many Karie houses at different parts of the Island.” The early Rarotongan evangelist Maretu recalls one named Te Atukura, and another called Pourau, located at Titima, housing “a community of young men, women and warriors. They stayed there, no one returned to their homes, it was a house of pleasure… There were one hundred and forty warriors in that kariei” (Maretu, 1983; 48, 52). The Rarotongan historian Te Ariki-Tara-Are records an ‘are kariei located at Aronu, and another at Pae-tai-oi. The Polynesian ethnologist Percy Smith describes an ‘are kariei located opposite the marae Arai-te-Tonga in Tupapa.

The season of karioi was a time for making oneself as beautiful as possible to find a long-term or short-term partner. Williams writes that – “In the Karie house the young women used to adorn themselves with the best of their cloth, perfume their bodies with scented oil and decorate themselves with odoriferous flowers. Their whole time was spent in sports and sensual enjoyments. The young men had nothing at all to attend to but to provide food for their guests, the females. Their whole time was devoted to the decoration of their persons, to their music, dancing, other sports and feasting.”

“Promiscuous intercourse would naturally result from such a state of things,” writes the Rev. Williams. “To these [‘are karioi] all the young unmarried people of both sexes repaired during the summer months. As soon as food began to fail they returned home to their respective habitations except such as during their inter course at the Karie might form such an attachment to each other as to determine on living together as man and wife” (Williams, 1984; 262).

Not all young people were permitted to attend the frivolities. Stephen Savage records that “tapairus or eldest daughters of the chiefs were not allowed to go to these houses, excepting on special occasions” (Savage 2012; 91).

Rev. William Wyatt Gill writes that a chief’s daughter was “expected to make her debut by taking part in the next grand dance. The greatest requisites of a Polynesian beauty are to be fat and as fair as their dusky skins will permit. To insure this, favourite children in good families, whether boys or girls, were regularly fattened and imprisoned till nightfall, when a little gentle exercise was permitted. If refractory, the guardian would even whip the culprit for not eating more.” These houses were known on Mangaia as 'are 'aka pana and their graduates referred to as ‘akapoari. In Pukapuka, the houses for bleaching and fattening were known as ‘wale kaitau’ (Beaglehole).

The debutante balls for the daughters of chiefs “invariably took place in the open air, by torchlight. About a year was required for getting up one such entertainment. This long interval was needed, first, for the composing of songs in honour of the fair ones, and the rehearsal of the performers; secondly, for the growth of taro, etc., etc., to provide the grand feast necessary. The point of honour was to be the fairest and fattest of any young people present. I know of no more unpleasant sight than the cracking of the skin as the fattening process proceeds; yet this calls forth the admiration of the friends” (Gill, 1979; 4-5).

For those attending the annual ‘are karioi, the amusements on offer included plays (nuku ‘enua or nuku tupuna - plays of the land or plays of the ancestors), comedy including word play, satire, burlesque and the lampooning of important persons, dances, acrobatics, boxing, wrestling, spear throwing, dart throwing, disc pitching and tests of strength. As well as performance there was instruction in composition and dance.

Vainerere Tangatapoto describes the Atiuan ‘are karioi as a place where “the expressive side of tribal life was taught and indulged in. The singing of love songs (ute), mourning chants (nakunaku) and commemorating chants (tuporo) were taught to young men and women at the same time and in the same place. Here too were taught and practiced the performance of dances, particularly the movement of the hands, body, head and legs. The development of grace and beauty had to be mastered” (Atiu an Island Community; 51).

Excavated foundation of an ‘Are Karioi, Keia District, Mangaia (Photo - Peter Bellwood, 1979, University of Auckland)/ 23120115

Te Ariki-Tara-Are locates the commencement of the kariei later in the year, during the fourth month of the Māori calendar, Erui-tutae-nui, noting “this was a time of plenty, and the people bedecked the emblems of the festival of fasting with garlands of flowers, and then built an immense “Kariei House” (in which to meet and sing and dance), and plenty of bruised bread-fruit and over-ripe bread-fruit was eaten by all the people.”

“After this the Eva-tipa was performed, a festival given in the form of a drama showing the mode of attack and defence in warfare, and throughout the performance of this festival all the actors, as they stepped through the various evolutions, emitted a most emphatic grunt.

“Then the Kapa-rakau was performed, which was an exhibition of attack and guard in spear-play, the whole being executed in time, with drum beating and chanting of war songs; spears clashed upon spears, thrusting, pairing and counter stroke. Then followed the ceremonial songs – the pæon of the victors –the dirge of the vanquished. This was a most impressive ceremony. The pæon of the victors was called Puapua-aki, and the dirge of the vanquished was called Tu-tau-maa.

“Next followed the ceremonial songs called Te-ava-ka-oora and Te-putu. These were the reply challenge songs on the return to battle – the vanquished endeavouring to wrest victory from the victors, that they might regain their prestige. This is how preparation was made for this ceremony:—The actors drank of the kava, then the murmurings of the gods were heard, great numbers of pigs were slain for the feast, then the whole of the actors engage in mimic warfare.”

A building of considerable size was needed to accommodate the performers and audiences. Williams exaggeratedly refers to the Rarotongan ‘are karioi as “Beautiful houses, some miles long.” Sir Peter Buck describes one, called Te Poniu-a-'au built in the old village of Vaitupa in Aitutaki with a rectangular floor 72 feet long by 34 feet wide. The archaeologist Peter Bellwood found “surviving remains consist(ing) of a basalt and coral pavement 25 × 9 metres” (Buck, 1944; 43).

These houses included a platform for performances, and space for spectators that doubled as places for feasting and sleeping.

While Williams suggests construction of the ‘are karioi was undertaken spontaneously by the young men of a village, Buck (1927, 36) observes: “They were usually built to the order of a high chief to add to his own prestige and for the entertainment of his unmarried daughters. In them, dancing, singing, and all indoor games and amusements took place, and it was the ambition of all to excel in these entertainments.” It is possible that special ‘are karioi were built for titled families while village ‘are karioi provided entertainment for everyone else.

In Tahiti 'arioi was also the name of a society of travelling entertainers. According to Rev. Williams the well documented “Arioiism of Tahiti (is not) much unlike the Karieism of Rarotonga except that it was more brutal, and filthy unjust and oppressive” (1984; 264).

References

Bellwood, Peter, 1969, Archaeology on Rarotonga and Aitutaki, Cook Islands: A Preliminary Report, Journal of the Polynesian Society, Volume 78, No. 4.

Buck, Peter, (Te Rangi Hiroa), 1927, The Material Culture of Aitutaki, T. Avery and Sons, New Plymouth

1944, Arts and Crafts of the Cook Islands, Bishop Museum, Honoloulu

Gill, William Wyatt, 1979, Cook Islands Custom, University of the South Pacific and Ministry of Education, Rarotonga

Te Ariki-Tara-Are, 1921, “Concerning the Ceremonies and Festivals brought by Tangiia to Rarotonga from Avaiki”, Journal of the Polynesian Society, Volume 30, No. 119.

Williams, John, 1984, Samoan Journals of John Williams, (edited Richard Moyle) ANU Press, Canberra