Hiroshima survivor shares harrowing story, calls for abolition of nuclear weapons

Friday 19 May 2023 | Written by Al Williams | Published in Features

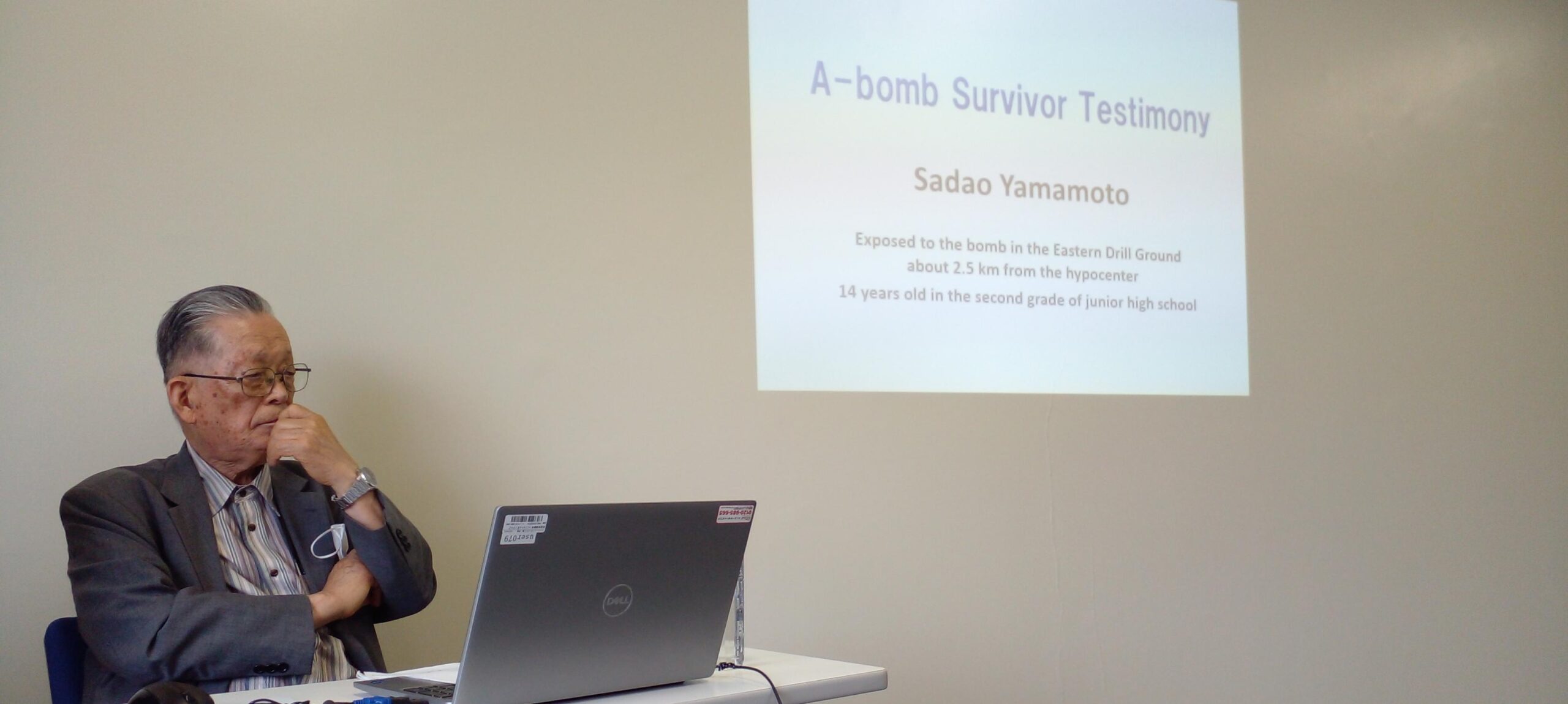

Hiroshima survivor Sadao Yamamoto gives his account of August 6, 1945. He was 14 at the time and now he wants everyone to raise their voices against nuclear weapons. PHOTO: AL WILLIAMS/23051802

Japan is sounding a loud and clear message ahead of the G7 Summit. It’s a no brainer really as I have seen journalists and interpreters alike, shed tears in recent days, as to the harrowing accounts of what happened in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Then the fallout, black rain, cancers and decades of suffering. There’s no irony Japan Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, as host of the summit, counts the city as his own electoral district and has made his made nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament his lifework.

As a visiting journalist among others from South Africa, Mongol, Mexico and Turkey to name a few, what I witnessed on Thursday (Japan time) at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum was raw emotion. Our interpreter introduced the museum deputy director, and through his words, she cracked up and fought tears as he briefed us on some of the stories we were about to see and hear. Some of the journalists were moved to tears. I felt a lump in my throat, and then proceeded to make my way through the Main and East Buildings, to experience an audio-visual tour which left me at the very least, quiet and reflective.

However, it was meeting Hiroshima survivor Sadao Yamamoto which left a lasting impact on me. He was 14 when Hiroshima was hit and about 2.5 kilometres from the hypocenter, and a second grader at junior high school, he among thousands of school students who were outdoors at the time helping demolish buildings around the city to create fire breaks in the event of enemy bombing. He cuts a fine figure in a suit, is an accomplished musician, he’s sharp, and answers the multitudes of questions our entourage of journalists throw at him. Through the interpreter I tell him that he looks smart and appears sharp. I ask him what still keeps him on the ball. He says taking care of a choir and managing its activities. He also visits the doctor once a month. He swears by group activities in that they “refresh your mind”. He spent two hours with us, giving his version of events and answering our questions.

Here’s a bit of what Yamamoto had to say. Around 130,000 people who were in Hiroshima on August 6 died by the end of 1945. Some 8187 school students from 39 schools and accompanied by 176 teachers were at work demolishing buildings that day in order to create fire breaks. The blast killed 6295 students and 132 teachers. He saw three B29 bombers fly over the city, “we all looked up thinking they were doing reconnaissance, just as the bombers were approaching they turned around, a tremendous bang and I was blown away by hot winds, when I regained consciousness I saw a huge pink flame”. He escaped into a valley and hid as he thought the bombing would continue. “I crawled out of the valley to look at the city but it was covered in white smog, I couldn’t see a thing. When I returned home, it was a mess, but everyone was safe, fortunately my family were all safe. My father was especially lucky as the building he was in at the time was only 680 metres away from the hypocenter, but shielded by a thick concrete wall. The next day my mother asked me to go and see my auntie, her house was about 500 metres away, I went to a place with high residual radiation, my aunt’s family were killed, only her son was left, I saw a dead soldier, a young girl with severe burns which had become infected. All the first-year students were wiped out.”

Yamamoto assumed all the students had died on the spot but it wasn’t until 1969 when he discovered through a television drama about the students at his school, that a third of the students had died on the spot, others died trying to make their way home, and some drowned in the river. Through music he conveyed their tragedy. He wrote music for them.

“People were told that if you give burn victims water they will die. All the students had begged for water but they were not given water. All those exposed begged for water. All those within a 1.2 km radius suffered severe burning and died within days.”

Then came radiation damage, exposure, and black rain. Long term damage included mental retardation and stunted growth in babies. Significant increases in cancer rates.

Yamamoto says there are 13,000 nuclear warheads in the world and “we must raise our voices against them”. He hated the United States, but now he has forgiven them. Japan started the war, he says, “We attacked the United States; the best way is to join hands with fellow democratic countries.”

“I can forgive.”

Yamamoto says countries must work together to abolish nuclear weapons. He would like President Joe Biden to visit the main exhibition at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and wants Biden to declare he would never use atomic weapons.

“I don’t know what I can do to prevent international conflicts; everyone must join hands to stop international conflict.”

Yamamoto also opposes nuclear power generation. “I hope it will be abandoned.”

Eighty per cent of A-bomb survivors support holding the G7 Summit in Hiroshima. A survey found survivors hope the leaders of each country will learn about the reality of the damage caused by atomic bombings and that it will lead to the abolition of nuclear weapons. The survey of 100 atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki was conducted by the Yomiuri Shimbun in cooperation with the Center for Peace at Hiroshima University and Hiroshima TV ahead of the G7. The interviews were conducted by reporters in person or by telephone between February and April. When asked if they appreciated the G7 being held for the first time in a city hit by an atomic bomb, 82 per cent responded affirmative. The most common reason given, with multiple responses allowed, was that it would provide an opportunity for leaders to learn about the reality of the bombings, a reason selected by 69 respondents, while 48 thought the voices of atomic bomb survivors would be brought to the world through the media, and 32 thought the leaders’ messages would increase momentum for nuclear abolition.

Meanwhile, six respondents answered that they did not appreciate it. Giving a reason, four respondents said that an effective agreement on nuclear abolition cannot be expected. When asked if the likelihood of nuclear weapons being used again has increased in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 80 of the respondents said that it has

- Al Williams is in Hiroshima, Japan to cover the G7 Summit. His trip was made possible by the Embassy of Japan in New Zealand.