Seeds of Christianity: The Gospel Pioneer to Aitutaki

Saturday 20 May 2023 | Written by Supplied | Published in Church Talk, Features

The aerial view of Aitutaki. COOK ISLANDS TOURISM/23051908

Historian and author Howard Henry has been fascinated by the birth of Christianity in the Cook Islands for many years. In a weekly series, Henry chronicles the arrival of Christianity to the Cook Islands and its role in building the nation. This is his third article in the series.

The first Europeans to step ashore on Rarotonga were apparently crew members from the “Cumberland” in early 1814. This vessel was under charter to a “Secret Sandalwood Company” of Sydney. The skipper of this ship was Captain Philip Goodenough while William Wentworth travelled as agent for the Sandalwood Company.

The crew of the “Cumberland” had spent six months on Rarotonga in search of sandalwood only to discover there was none to be found. So they loaded the vessel with a cargo of “nono” wood instead.

Shortly before the “Cumberland” left Rarotonga, hostilities broke out between the crew and some of the people of Rarotonga as a result of persistent theft on the part of the European visitors. The critical act which brought hostilities to a head was when two crew members from the “Cumberland” stole coconuts belonging to Makea Tinirau Ariki at Arai-te-Tonga.

Read more:

- ‘They called this island Wytootakee’

- Christianity created a Nation: The arrival of the Gospel

- Spreading the Gospel of history

- ‘You’ve been worshipping nothing but pieces of wood’

- Letter: Living under God’s blessing

- ‘Let us worship but one (true) God’

- Death of Ariki’s daughter, an attempt to introduce Christianity to Mangaia

- ‘The Spirit of God is forever present … everywhere – all the time’

In those days the worst crime a person could commit was to steal from an Ariki. The penalty for such an offence was death because that was the “Law of Rarotonga” in Pre-European times.

Once that crime of theft had been committed, Rupe, who was a son of Makea Tinirau Ariki, went after the two crew members concerned and apprehended them. He then handed down “Justice-Rarotonga-style” and killed them both. That started a chain reaction which saw several other crew members being killed including Captain Goodenough’s girlfriend. Her name was Ann Butcher.

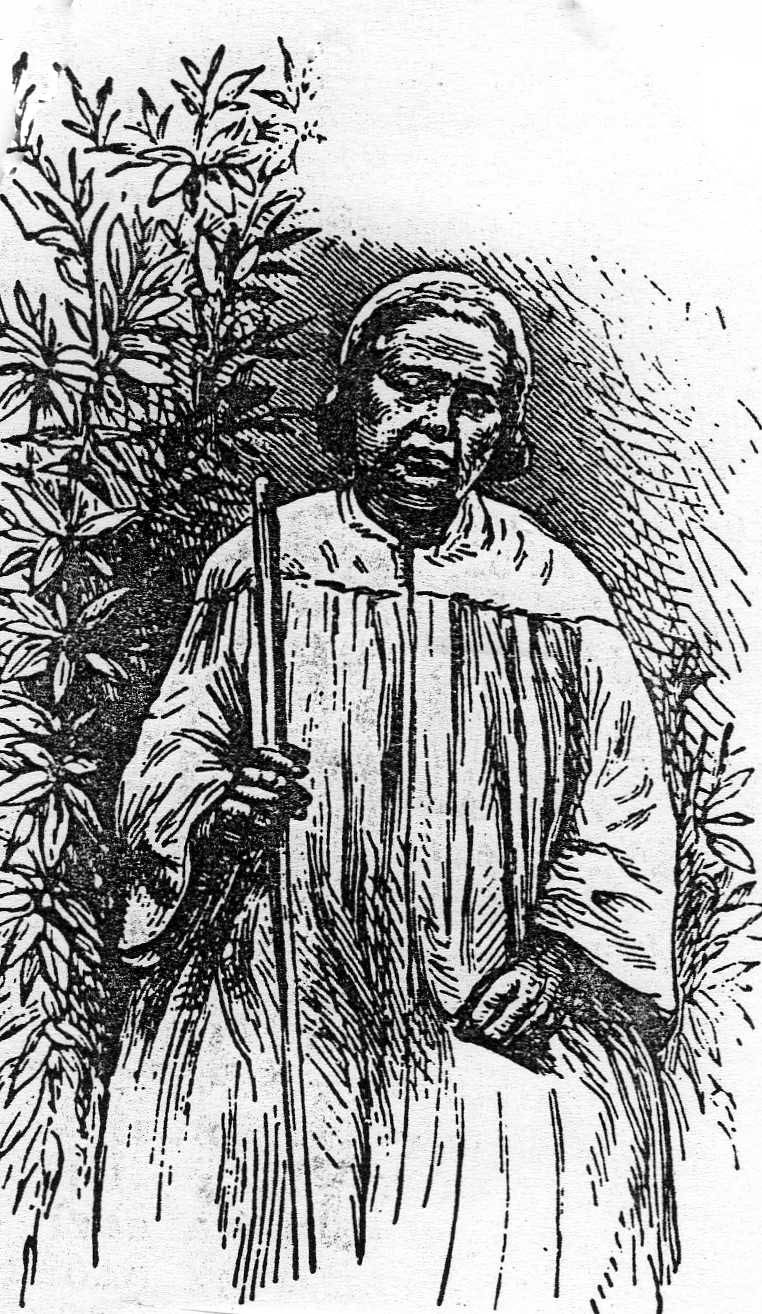

Tepaeru-Ariki as depicted in later years. Tepaeru-Ariki was the daughter of Rupe. She was also the grand-daughter of Makea Tinirau Ariki of Arai-te-Tonga, Rarotonga. She was taken to Aitutaki by the captain of the “Cumberland” in late 1814 and subsequently taken in by Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki of Arutanga. Tepaeru-Ariki was one of the first to embrace Christianity following the arrival of Papehia and Vahapata on 26 October 1821. When Aaron Buzacott opened the Takamoa Theological College on Rarotonga in 1843, one of the first students that he took in for Theological Training was a son of Tepaeru-Ariki. His name was Rupe. 23051906

In response to this, Goodenough abducted two women from Rarotonga and then made his departure.

As the “Good Behaviour Bond” Regulations, as initially promoted by Reverend Samuel Marsden, now existed in New South Wales, Captain Goodenough was aware that he could not arrive in Sydney with these two women from Rarotonga on board his ship. To do so would result in hefty fines for both he and those businessmen who had sent the “Cumberland” to Rarotonga by way of charter.

According to Goodenough’s navigation charts, the nearest island to Rarotonga was Aitutaki. So the “Cumberland” sailed there at which point the Captain had his abducted captives thrown over the side and left to be picked up by the local inhabitants off the Arutanga Passage … that was in late August 1814.

Captain Goodenough and the “Cumberland” then returned to Sydney where it was discovered that the cargo of “nono” wood was commercially worthless. This meant that the expedition to Rarotonga had been a financial disaster for the businessmen who had been the foundation members of the Sandalwood Company of Sydney.

One of the women left by Captain Goodenough at Aitutaki was Tepaeru-Ariki. She was born on Rarotonga around 1795 and her father was Rupe. He was one of the younger sons of Makea Tinirau Ariki. So Tepaeru-Ariki was his grand-daughter and a person of royal blood in terms of her standing on Rarotonga.

The second woman abducted was Mata Kavaau. She was a niece of Kainuku Ariki of Takitumu.

When Tepaeru-Ariki and Mata Kavaau reached the shore at Arutanga, they were taken to Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki who was the then Tamatoa Ariki of the Arutanga District. He inquired as to who they were and asked for an explanation as to how they came to be “dropped off” at Aitutaki.

Tepaeru-Ariki told how she and Mata Kavaau had been abducted by those on the “Cumberland”. So they had been brought to Aitutaki against their will and subsequently thrown over-board.

Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki knew about Rarotonga. He was aware that Makea Ariki was of some standing on that island and so he recognised Tepaeru-Ariki to be a person of royal blood.

The Ariki therefore took her and Mata Kavaau to live with him and his family. He instructed those within his tribe to treat these two women with the same status of respect as if they were his blood daughters.

A short time after arriving, Tepaeru-Ariki discovered there were two men living on Aitutaki who were also from Rarotonga. Their names were Tairi and Teiro. They had initially gone fishing in their canoe outside the reef at Takitumu where they were caught up in a storm and ended up being blown out to sea.

They reached Aitutaki sometime later where the two men landed and were taken in by the people of that island.

It was Tepaeru-Ariki who told Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki and others about the Europeans on the “Cumberland”. She also told of the many useful possessions the Europeans had on their ship of the kind she and the people of Rarotonga had never seen before.

She said the visitors had all sorts of material goods which made them extremely prosperous and wealthy.

The general belief on Aitutaki was that the traditional gods created everything in the universe and provided everything that existed on earth. Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki and others therefore came to the conclusion that the European God or Gods were extremely generous to their subjects.

These European God or Gods had so much more to offer the “earthly subjects” and all this was confirmed by Tepaeru-Ariki as a result of what she had personally seen during her time of association with crew members of the “Cumberland”.

As a result of this perception, the “seeds” of Christianity were firmly being planted on the island with the view taken that the European God or Gods were so powerful and kind to their respective subjects, that it made the traditional gods of Aitutaki appear inferior, less powerful and far less generous.

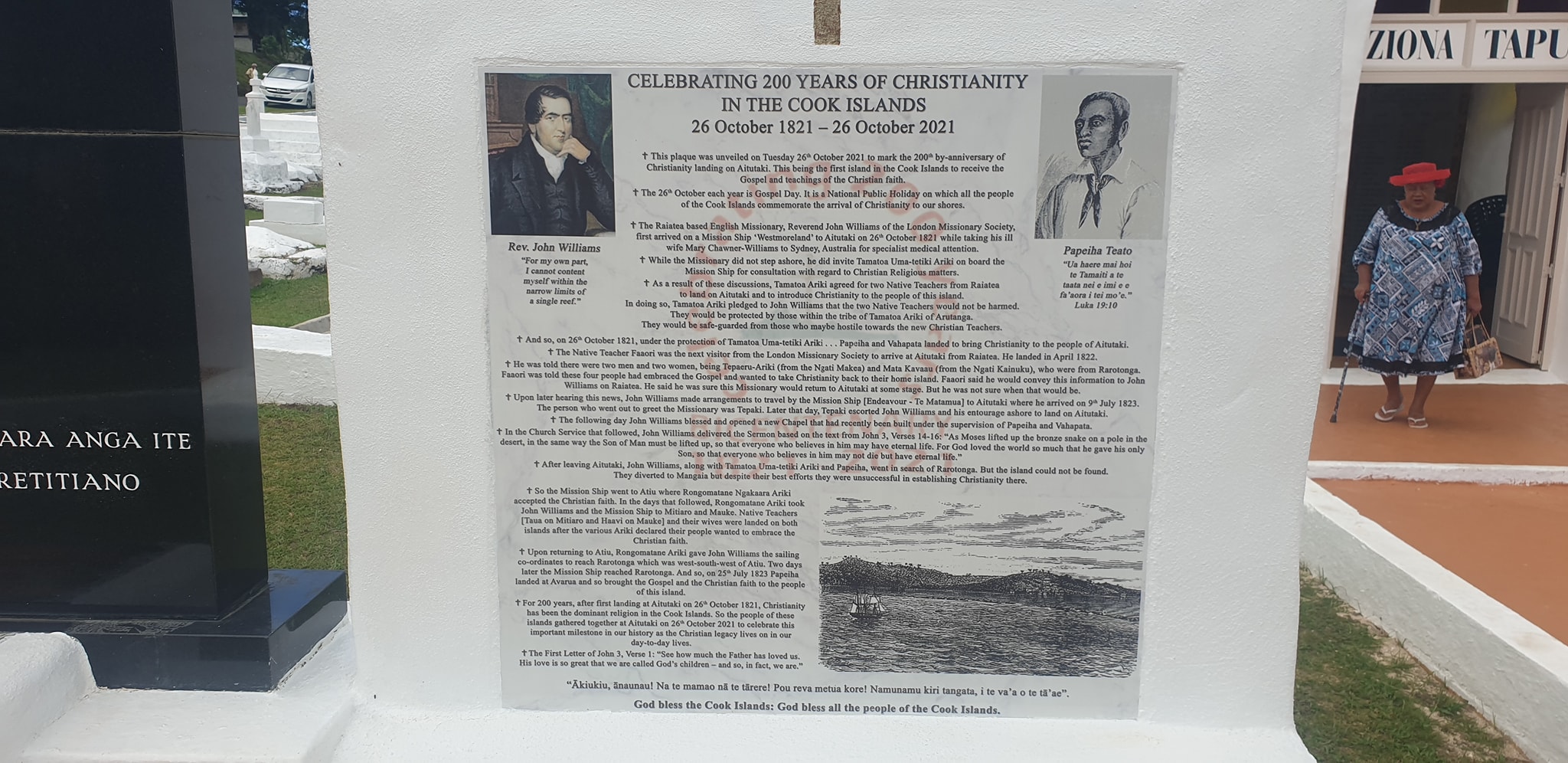

A brief history on the Arrival of Christianity to Aitutaki. Picture: Aitutaki 2021 200 years Bicentennial Celebration Official/23051909

In addition to that, Tamatoa Uma-Tetiki Ariki and others of Aitutaki had either heard of, or seen for themselves, at least five other European ships which had called at their island in the years prior to the arrival of the “Cumberland” in late 1814.

These visiting vessels included the following:

- The “H.M.S. Bounty” under Captain William Bligh which called on 11-12 April 1789.

- The “Pandora” under Captain Edward Edwards which called at Aitutaki in May 1791.

- The “Resolution” which sailed with the “Pandora” – also in May 1791.

- The “Providence” under Captain William Bligh called at Aitutaki for a second time on 25 July 1792.

- The “Assistant” which sailed with the “Providence” – also on 25 July 1792.

It is likely that other vessels had also called at Aitutaki including whalers and ships which had started travelling between Sydney and Tahiti in the years after 1803. So the number of ship visits to Aitutaki by European manned vessels were no doubt more than those listed above during the pre-Christian period.

In early 1821, Mrs Williams, wife of Reverend John Williams, became ill on Raiatea.

When her illness failed to improve, the Missionary, John Williams concluded that his wife had to go to Sydney to receive medical attention. He was very much aware of Aitutaki as a result of Captain William Bligh and the “H.M.S. Bounty” which had called there on 11-12 April, 1789.

And so John Williams later left Raiatea on the Mission Ship with two “Native Teachers” in the hope of placing them on Aitutaki to begin their missionary work.

On 26 October 1821, Reverend Williams reached the island which he described as follows: “On the arrival of the vessel at Aitutaki, we were soon surrounded by canoes; the natives were exceedingly noisy, and presented in their persons and manners all the features of savage life. Some were tattooed from head to foot; some were painted most fantastically with pipe clay and yellow and red ochre; others were smeared all over with charcoal, dancing, shouting and exhibiting the most fantastic gestures.”

“We invited the Chief Tamatoa on board the vessel. A number of his people followed him. Finding that I could converse readily in their language, I informed the chief of what had taken place in Tahiti and Society Islands with respect to the overthrow of idolatry.

“He asked me, very significantly, where great Tangaroa was. I informed him that he, with all the other gods, was burned. He asked me where Koro of Raiatea was. I replied that he too was consumed with fire; and that I had brought two teachers to instruct him and his people in the word and knowledge of the true god, that they might be induced to abandon and destroy their idols, as others had done.

“On my introducing the teachers to him, (Papehia and Vahapata) he asked me if they would accompany him to the shore. I replied in the affirmative, and proposed that they should remain with him. He seized them with delight, and saluted them most heartily by rubbing noses, which salutation he continued for some time.” (Source: “A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands”, by John Williams. Published by John Snow and Co., London, England, 1837)

While Reverend Williams and Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki, were holding their various discussions, a number of men of Aitutaki, who had also boarded the Mission Ship, found the most interesting sight to them was the Missionary’s four-year-old son.

They were absolutely fascinated by him.

They could not stop staring at this little “white boy” as if he was a real unusual “oddity”.

According to Reverend Williams: “… the people were becoming clamorous in their demands for the child … and a good deal of whispering going on among them, with significant gestures, first looking at the child, then over the side of the vessel, his mother was induced to hasten him into the cabin, lest they should snatch him from her, leap into the sea, and swim to the shore.” (Source: “A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands”, by John Williams. Published by John Snow and Co., London, England, 1837)

In due course one of their members approached Reverend Williams and asked if they could take the young boy ashore and keep him on the island. The Missionary was naturally very suspicious to this request. Even though he had no intention of allowing his son be taken away, he did ask in a polite sort of a way, as to what would happen to his son – should the boy be taken ashore.

Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki quickly replied: “We will make him our king.”

Need-less-to-say … Reverend Williams respectfully declined this request.

Prior to the departure of Papehia and Vahapata from the Mission Ship, Reverend Williams sought an assurance from Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki that he would personally provide protection for these two teachers and not allow them to be harmed or ill-treated by any other person or persons on the island.

Tamatoa Uma-Tetiki Ariki was not “backward in coming forward” to give Reverend Williams his pledge of protection over Papehia and Vahapata. And so this pledge enabled the two men to land on Aitutaki as they did on 26 October 1821.

Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki and his tribe living in the District of Arutanga had no comprehension of what Christianity actually involved in terms of spirituality, but they did have an appreciation of the material wealth this European God generated. So it was on the basis of gaining access to this material wealth, that the Gospel was allowed to land on Aitutaki in the manner that it did.

But it was only after Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki had given Reverend Williams his personal guarantee that no physical harm would come to the new arrivals, that Papehia and Vahapata then climbed into one of the canoes, with but a few possessions, and were subsequently taken ashore at Arutanga.

As Reverend Williams left Aitutaki and headed for Sydney, and as Papehia and Vahapata stepped ashore at Arutanga, Aitutaki, little did these two “Native Teachers” realise that Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki and many of his tribe, had already concluded that they wanted to learn more about the “European God”.

They were very keen to find out what this God had to offer.

This was because the “seeds of Christianity” had already been firmly planted on Aitutaki before Reverend Williams ever arrived and long before Papehia and Vahapata actually landed.

The people within the Tamatoa clan of Arutanga had been told all sorts of “stories” about the European God.

They had been told it was more powerful, more generous to its subjects and was far stronger than any of the traditional gods the people of Aitutaki, or Rarotonga, had ever known.

The person who had told Tamatoa Uma-tetiki Ariki and others about this was Tepaeru-Ariki, a woman from Rarotonga.

So Tepaeru-Ariki was a “Gospel Pioneer” to Aitutaki several years before Reverend Williams brought Papehia and Vahapata to this island, in the manner that he did, on 26 October 1821.

References

John Williams: “A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands”, Published by John Snow and Co., London, England, 1837.

Papehia Manuscript: “An Account of the coming of the word of God to Rarotonga”, Polynesian Society, Wellington, NZ, 1930.

Howard Henry: “Christianity created a Nation”, Sovereign Pacific Publishing Company, Rarotonga, Cook Islands, 2021.