Painting with scissors: exploring Tivaivai’s links to European modern art

Saturday 7 January 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Art, Features

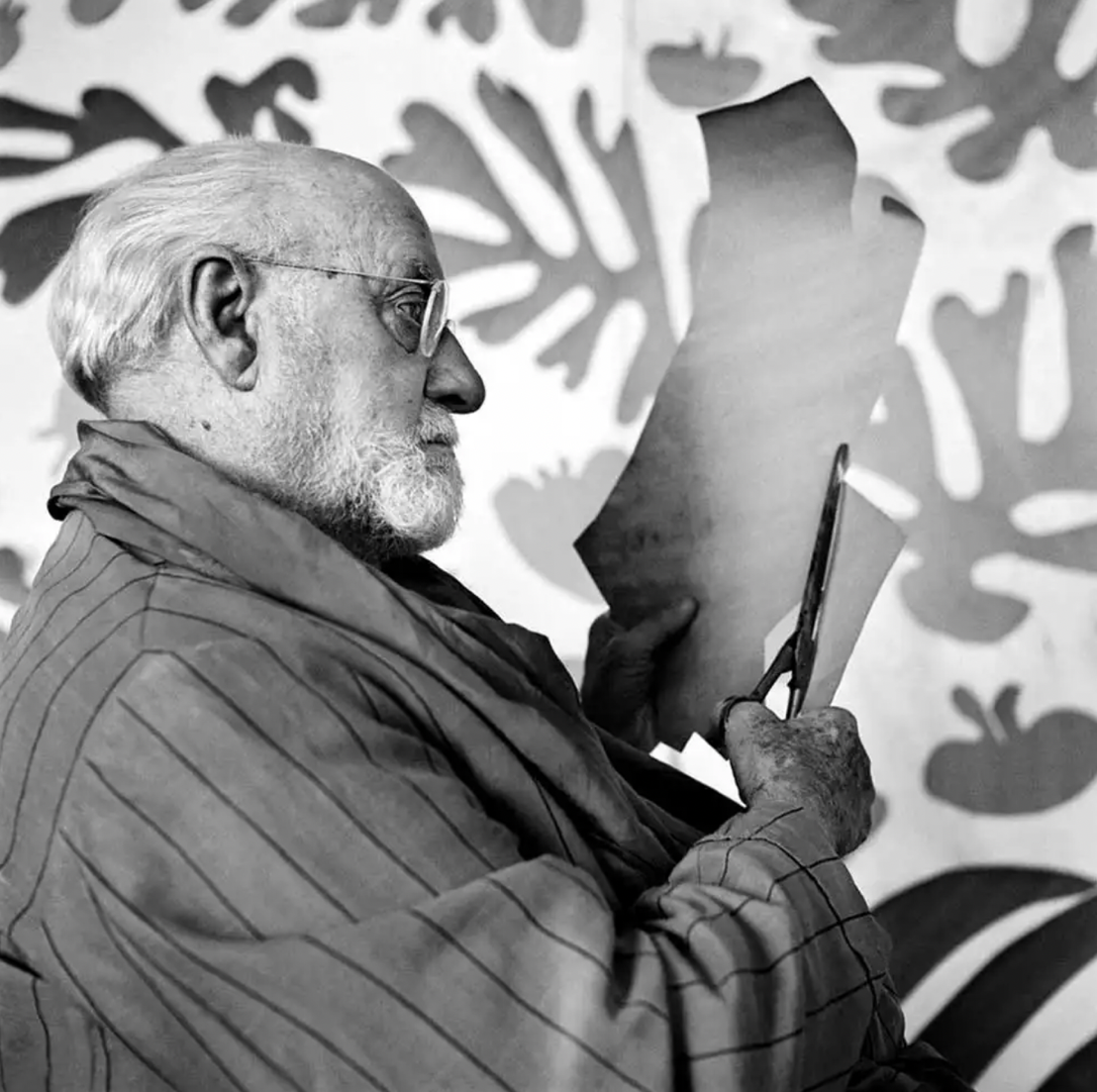

Henri Matisse working on a cut-out in his Nice studio. (Getty Images)/ 23010621

A major art exhibition in Sydney explores the link between tivaivai and Henri Matisse, the great French master of modern art.

A recent art exhibition in Sydney celebrated the work of the great French painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954) with a side exhibition of tivaivai made by Cook Islands women from Southwest Sydney.

The connection between Matisse, one of the most celebrated and popular artists of the twentieth century, and Polynesian tivaivai results from a visit the artist made to Tahiti in 1930.

According to writer Diana Rico, “Matisse lived in Tahiti—primarily the Tuamotu islands—for two and a half months, drawing, photographing, taking notes, and observing the sea, sky, vegetation … (living) a Robinson Crusoe–like existence, getting up at dawn, canoeing, swimming, and diving amid the coral and fish. Although he produced little finished artwork there, the Tahitian sojourn had a powerful influence on his later work.”

Henri Matisse, Snow Flowers, 1951 (photograph: Scala Florence / Museum of Modern Art, New York

/Succession Henri Matisse)/ 23010622

In Papeete, Matisse befriended a Moorean woman Pauline Schyle (nee Atamai) and her husband Etienne. Mme Schyle introduced him to the art of Tahitian tifaifai, later gifting Matisse two Tahitian tifaifai pa’oti (tivaivai manu) – coloured cloth cut in a snowflake pattern, sewn onto a backing of different coloured cloth.

Much of Matisse’s subsequent artwork was composed of coloured cut-outs attached to a background of contrasting colour, drawing inspiration from Tahitian tifaifai pa’oti.

“The manufacture and mode of display of tifaifai are prototypical of Matisse’s own procedure for making his independent cut outs” writes art historian John Klein. “First he cut designs in coloured paper with scissors; then with assistance he arranged them on a contrasting background until he achieved the coloristic, formal and spatial effects he sought … the shapes were usually fixed provisionally with pins until a final decision (on lay out) …”

The skill of both the tivaivai ta’unga and of Matisse, the master artist, lay in the cutting and assembly of the cut-out pieces and the intricate blending and matching of colour.

Common motifs in both tivaivai and Matisse’s cut-outs include the breadfruit, the acanthus, the tiare, corals, animals of the sea and air - Matissse’s work largely differing from tivaivai in spatial layout. The cloth fabric of the tifaifai pa’oti is folded twice before being cut, giving the design a biaxial symmetry, whereas Matisse’s cut outs demonstrate much looser organization(Klein, 1997; 61).

Klein talks approvingly of “Matisse’s apparent appropriation of an indigenous art form in the service of an original French expression” (1997; 63-4) in which “the formal elements, the technical procedure and the iconography of the tifaifai” are adapted to French art practices.

The art reviewer Jonathan Jones is rather less approving of such ‘apparent appropriations’ of Polynesian art by European artists. Reviewing the British Royal Academy’s exhibition of Polynesian art for the Guardian in 2018, he writes: “It was the European modernists who got all the wealth and fame while their collections of Oceanian art went down in art history as troves of ‘raw material’ for their supposedly unprecedented ideas. Wandering through the Royal Academy’s intoxicating forest of sculpted symbols from the Pacific, I am inclined to see the whole thing more bluntly … This dazzling exhibition is full of the art the fathers of modernism ripped off ... it’s clear the sheer scale of modern art’s debt to the Pacific has yet to be properly acknowledged, or fully understood.” (The Guardian, 25 September, 2018)

From either point of view, the result, in the words of Justin Paton, one of the Sydney exhibition’s co-curators, was “one of the great flowerings of modern art”.

Critics of the Sydney Exhibition “Matisse Alive” were united in regarding the incorporation of Cook Islands tivaivai into the exhibition, as one of its major highlights. Chloé Wolifson writing in the art journal Cobosocial praised the Cook Islands tivaivai as “the primary revelation of “Matisse Alive”. These works, made over recent decades, share an unmistakeable connection with Matisse’s cut-out works. Their vibrant colours and bold shapes explore floral, vegetation and marine motifs and are executed with exceptional skill.”

Art critic Joe Frost writing in Artist Profile considered the tivaivai collection one of the “better moments” of the exhibition, writing that the “tivaevae of the Cook Islands quilters, possessed a visual logic and sense of touch that stood well beside Matisse.”

Maud Page, director of collections at the Art Gallery of NSW spoke enthusiastically of “These magnificent textiles with their symmetrical flowers, fruit and fronds (that) leave no doubt as to their impact on Matisse’s cut-outs. For us it is a way to honour women’s work that is celebrated throughout the Pacific.” (Emma Joyce, Exhibition review, Broadsheet.com.au)

As well as the tivaivai display, the “Matisse Alive” exhibition featured four commissioned ‘Solo Projects’ by four contemporary artists – two with ties to the Pacific.

Interestingly, these artists are all individually named in reviews, while the tivaivai creators are recorded simply as “members of the Sydney Cook Islands community.” Cook Islands’ art forms, such as tivaivai, dance, musical composition, etc. are traditionally collective endeavours, the product of many hands while the focus of European art is on the individual creator. The ‘invisibility’ of the tivaivai artists, it has been argued, also results from tivaivai being both ‘women’s work’ and ‘craft work’ – both historically undervalued by the art market.

Single named artists can attract high prices for their work. The record price for a work by Henri Matisse is $81 million, sold at Christies, New York in 2018. On the other hand, tivaivai have traditionally created prosperity in what Dr. Jane Horan calls the “realm of mutuality” rather than “the realm of the market”, reinforcing personal and family relationships rather than generating money.

As the art of tivaivai becomes an increasingly individual pursuit, there are moves afoot to create a market for these works with named individual ta’unga producing tivaivai as commodities attracting high prices in the art market. This marketisation arguably commenced with the sale of a large, intricate tivaivai ta’orei to the Rarotongan Hotel for an unknown figure (said to be around $10,000) in 2001 (Cook Islands News, 10 April 2001).

As interest in tivaivai as art commodities increases, it will be interesting to see if the social values of tivaivai, which in Jane Horan’s view, materialise key Cook Islands values of kinship and aro’a, succumb to their new monetary value. Perhaps neither or both. After all, as Horan astutely observes, Cook Islanders have become expert in successfully negotiating the multiple tensions between their own “economy of mutuality” and the western market economy.

The “Matisse Alive” exhibition was staged in conjunction with the major exhibition Matisse: Life & Spirit, Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou, Paris at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2022.

References

John Klein, Matisse after Tahiti: The Domestication of Exotic Memory in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 60. Bd., H. 1 (1997), pp. 44-89

Jane Horan, 2013, Tivaivai in the Cook Islands Ceremonial Economy, PhD thesis, University of Auckland