A young Atiuan warrior’s 1972 migration to Rarotonga

Friday 2 September 2022 | Written by Supplied | Published in Features

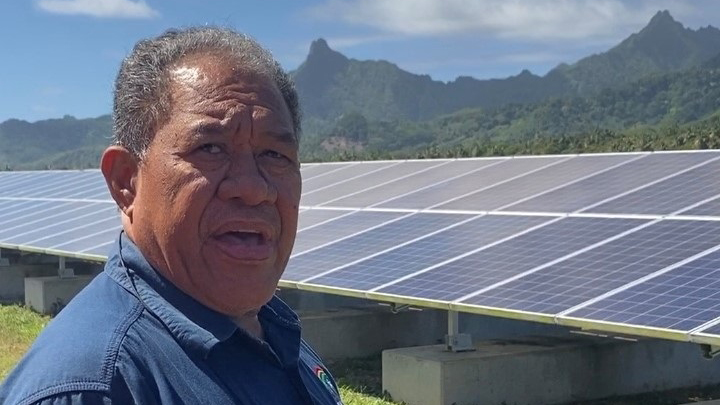

Tere Akava, 66, dedicated 49 years of service to supplying the Cook Islands with power. - 22090240

In October 1972 Tere Akava from Atiu said his final goodbyes to his grandparents as he left for Rarotonga, carrying only a small suitcase and a dream of becoming a motor mechanic.

Akava, born in July 1956, was raised in Atiu by his grandparents. In 1972 he and about 15 other school friends left the island to attend a careers expo in Rarotonga.

“That was not my first time travelling to Rarotonga by ship,” Akava says, “but this time was special because I was with school friends, and we were going to look at possible careers.”

“The trip was exciting and, at the same time, a little scary because we did not know what was ahead.”

Akava says he was interested in becoming a motor mechanic, working in Arorangi at the Public Works Department – now known as Infrastructure Cook Islands – but during the trip he also visited the Electric Power Supply station – now known as Te Aponga Uira (TAU), in Tukatimoa.

“My preference was motor mechanics,” he says.

“I liked using tools and fixing things, and I did not mind getting a little dirty.”

After returning from Atiu from the expo, Akava spoke to his grandparents about his dream of moving to Rarotonga, which would ultimately mean never seeing them again.

“They knew they were saying goodbye to me for good.

“I was sad, and I was also excited that I would be working on Rarotonga. I booked my seat on the next ship out of Atiu with the shipping agent.

“In October 1972, I said my final goodbye to my grandparents and travelled to Rarotonga carrying a small suitcase. I did not know when I would return to Atiu again. All I knew was that I wanted to be a motor mechanic, and I had to succeed.”

On arrival to Rarotonga, Akava says the environment was very different from Atiu.

“Rarotonga had many cars, bikes, trucks, buggies and bicycles on the road.

“Saturday was a hectic day in Avarua. People you would not see during the week were in Avarua on Saturday mornings selling and buying goods.

“There were also a lot of people on Rarotonga. There were also plenty of Papa’a people working in different places. People that worked in offices looked very smart. They wore high socks, shoes and well-pressed shorts and shirts.

“I noticed how busy Rarotonga was and the different classes of people. As a young Atiuan warrior, this place full of opportunities was heaven.”

Akava’s parents lived in Takuvaine but he opted to stay with his aunty in Tutakimoa. After settling in, he started casual work on the Avarua docks, loading and unloading cargo, working for the Union Steamship Company.

“During this time, I saw many families leave Rarotonga with a dream of working in New Zealand.

“I heard the stories on the dock from these people leaving. They were going to get $500 a week working in the factories in New Zealand.

“That kind of information captured my attention as a young person, but I still wanted to stay and work on Rarotonga. Many Pa Enua and Rarotonga families left Rarotonga, and I have not seen these people return since.”

After a few months of working at the dock, Akava says he wanted to find a fulltime job and pursue his dream of becoming an engineer at Public Works.

But Akava says his family did not have the transport he required to go to Arorangi from Tutakimoa daily.

“Though this saddened me, I understood the hardship and the fact that I had to find something else. I had to find work at a place nearby.”

So instead at 17, Akava started working for the power station in the lines division in January 1973.

“I worked on erecting power poles and putting up the lines… I also dug trenches.

“No diggers back then. Everything was ‘manpower’. I was using a pick and shovel every day.

“It was very dangerous to erect a concrete power pole because this was done using a jack and pulley system. It was all manual and very risky.”

Akava was earning 30 cents an hour – around $13 a week after tax.

“That was a lot of money back then. It was much more than I was making at the shipping yard.”

In 1976, a year after the new power station was installed in the Avatiu Valley, Akava went to the Solomon Islands to start his apprenticeship studies with two other people.

“In the first year at (the) Solomon’s, we had to pass mathematics, theory, regulations and science. If we failed, we had to leave the program.

“I passed, but I found it very hard because I learned about the metric system in the Solomons for the first time. Before that, I only knew the imperial system (feet/ inches).”

Between his time at the Solomon Islands Akava went to Atiu to set up the island’s power station and then went to Mauke to manage the station over there.

In January 1979, Akava was back in the Solomon Islands for his final year of study and became a certified electrical tradesperson. His study continued from 1980 to 1982 via correspondence. Over the years he has also continued learning about his craft in New Zealand, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Japan.

Now at 66, Akava has retired from TAU after dedicating 49 years of service to supplying the Cook Islands with power.

“I am happy to retire, knowing I gave it my best,” he says.

Information gathered from Te Aponga Uira’s story, “A life time of service to TAU”. Rewritten by Caleb Fotheringham.