Assessing the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Thursday 25 August 2022 | Written by Supplied | Published in Economy, National

Finance minister Mark Brown pictured at the opening of the Asian Development Bank back in 2020. Photo: FILE

The establishment of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016 – and the decision by Western donors, with the notable exceptions of the US and Japan, to join it – seems somewhat remarkable from today’s vantage point.

This is because it represents one of the few recent examples of a response to Beijing’s rise that has emphasised collaboration over competition, writes Cameron Hill is Senior Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

In the intervening years, China’s expanding geo-economic footprint and the various countermeasures enacted by the US and its allies, including in the infrastructure sphere, have seen a fracturing of economic cooperation between Beijing and the West. This fracturing has been accelerated by the pandemic. But the AIIB has endured.

As outlined previously, the AIIB is just one element of China’s development engagement. Much of the (more opaque) finance associated with high-profile bilateral schemes such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is usually delivered via China’s state-owned banks and enterprises. With China’s overall development finance pledges estimated at around US$85 billion a year, its current capital subscription to the AIIB (US$29.7 billion over five years) represents only around 7% of Beijing’s total annual semi-concessional and non-concessional commitments.

But China is, by far, the biggest contributor to the AIIB and therefore has the largest single vote share (26.58%), followed by India (7.59%), Russia (5.97%), Germany (4.15%) and South Korea (3.49%) (Figure 1). Australia (3.45%) has the sixth largest vote share. AIIB has five Pacific members – Cook Islands, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu – plus Timor-Leste, with a total vote share of 0.82%. Papua New Guinea is a prospective member.

Compared to its multilateral development bank (MDB) peers, the AIIB is still small in terms of its approved lending portfolio (Figure 2), particularly when compared to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank. But 2021 was a record year for lending growth — with 50 new project approvals worth around US$9.6 billion — bringing the AIIB closer to its stated annual investment target of US$10–12 billion.

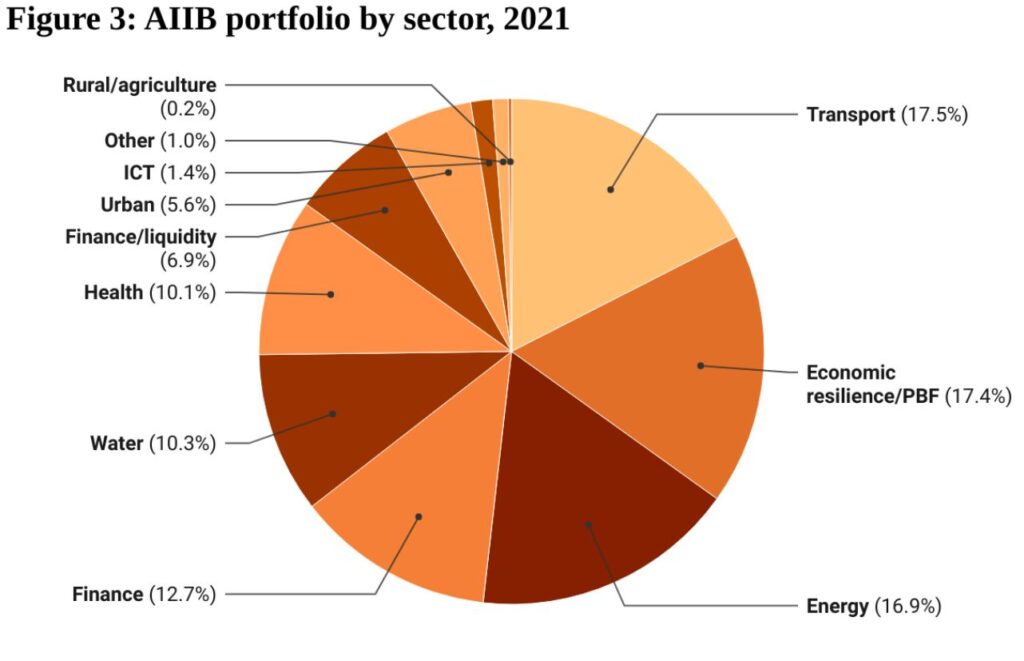

While traditional infrastructure sectors (energy, transport, water) are prominent in the AIIB’s portfolio, the COVID-19 crisis has seen the Bank expand lending for both public health (financing for vaccines) and direct budget support (“economic resilience/policy-based finance (PBF)”). The latter is co-financed under ADB or World Bank terms. As at March 2022, budget support represented AIIB’s second largest lending category, just slightly less than transport (Figure 3).

In terms of portfolio performance, the Bank established its first evaluation and learning policy in 2021 and, while there is no standalone independent evaluation office, the policy establishes a direct reporting relationship to the AIIB Board. The AIIB has not yet developed a specific policy to ensure its projects promote gender equality.

In terms of destinations, AIIB projects are heavily concentrated in large, middle-income developing economies, with the Bank’s top five borrowers by value (as at March 2022) accounting for almost two-thirds (US$20 billion) of approved, country-specific (i.e. excluding 'multi-country') loans. The remainder of approved loans (US$11 billion) are spread across 27 countries (Figure 4). AIIB’s operations in Russia and Belarus have been suspended and remain under review following the former’s invasion of Ukraine in February.

As well as being the second largest shareholder, India is the AIIB’s largest borrower by value, with US$8.1 billion (about 24% of AIIB’s total portfolio) worth of projects. Officials have described India’s support for the AIIB – as opposed to its distinct lack of enthusiasm for the BRI – as a choice between “connectivity through consultative processes or more unilateral decisions”.

China is the AIIB’s second largest borrower. In this sense, the AIIB represents a microcosm of China’s unique position as both a leading global lender and an enduring borrower of international development finance – the AIIB provides China with sovereign and non-sovereign loans, just as Beijing continues to both contribute to and borrow (non-concessional finance) from other MDBs, including the World Bank and the ADB.

Given its non-concessional loan terms and the scarcity of high return infrastructure projects, the AIIB only has three investments in the Pacific – two budget support loans in Fiji (co-financed by the ADB) and one budget support loan in the Cook Islands (co-financed by New Zealand and the ADB). The AIIB has established a grant-funded Project Preparation Special Fund and a more concessional "Special Fund Window" to increase lending to lower income members.

There have been multiple assessments over the last few years of the extent to which the AIIB is living up to its founding mantra of “lean, clean and green”. It is certainly “lean” – while the AIIB’s lending portfolio is about a third of the size of that of the ADB, it has less than 10% of the staff. Nor does the AIIB have representative offices in any client countries. The Bank aims to increase its staff headcount to 800-900 by 2030, and has just announced the creation of its first overseas office, in Abu Dhabi.

The AIIB has also attempted to streamline project preparation processes, the slowness of which has been one of the main criticisms of the established MDBs. In doing so, the Bank has ended up relying heavily on co-financing existing projects developed by the ADB and the World Bank. Unlike the other MDBs, the AIIB only has a part-time, non-resident board of directors. Another important structural difference with other MDBs is that the AIIB does not have formal replenishments of its capital fund; while this gives the Bank and its clients more autonomy, it limits the ability of shareholders to directly link funding with improved performance, management reforms and strategic focus.

The AIIB has clearer policies on anti-corruption and transparency (“clean”) than China’s bilateral financing initiatives, which rate among the least transparent in the world. Like the ADB and the World Bank, the AIIB uses international competitive bidding and maintains a public list of debarred companies, individuals and entities that are excluded from bidding for AIIB projects, including dozens of Chinese entities.

Nevertheless, recent assessments have raised concerns about the Bank’s approach to due diligence, a lack of independent oversight of its environmental, social and accountability frameworks, and the Bank’s heavy reliance on its clients to monitor policies and standards. There is also the issue of the AIIB’s role as the host institution for the China-led Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (MCDF), in particular the lack of clarity surrounding the latter’s relationship to the BRI.

It is against the last criterion, “green”, where the AIIB has struggled the most. According to a civil society assessment published in 2021, for every US$1 the Bank has invested in renewable energy, it has spent almost twice as much on fossil fuel projects. Based on 2020 figures, the AIIB has been ranked lowest among all MDBs in terms of the proportion of its total portfolio (12%) invested in climate finance. And the Bank has yet to finalise a new energy sector strategy detailing how it plans to align its programmes with the climate targets contained in the Paris Agreement. The Bank has committed to end support for coal-related projects and to make climate finance 50% of its total project approvals by 2025

With the prospects for future trilateral cooperation appearing very slim, the AIIB represents one of the few remaining platforms for Australia to engage with China on regional development issues. This is an important function. But while support for the Abbott government’s 2015 decision to join the AIIB was bipartisan, it is unclear how Australia’s engagement with the AIIB will evolve in an era characterised by a much more sceptical attitude toward China’s development forays.

In 2020, the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has approved a US$20 million (NZ$28 million) loan to the Cook Islands to meet a cash crunch caused by Covid-19 pandemic.

Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views represent those of the author only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Cameron Hill is Senior Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. He has previously worked with DFAT, the Parliamentary Library and ACFID.