Thomas Wynne: What’s in a vote?

Saturday 14 October 2023 | Written by Thomas Tarurongo Wynne | Published in Editorials, Opinion

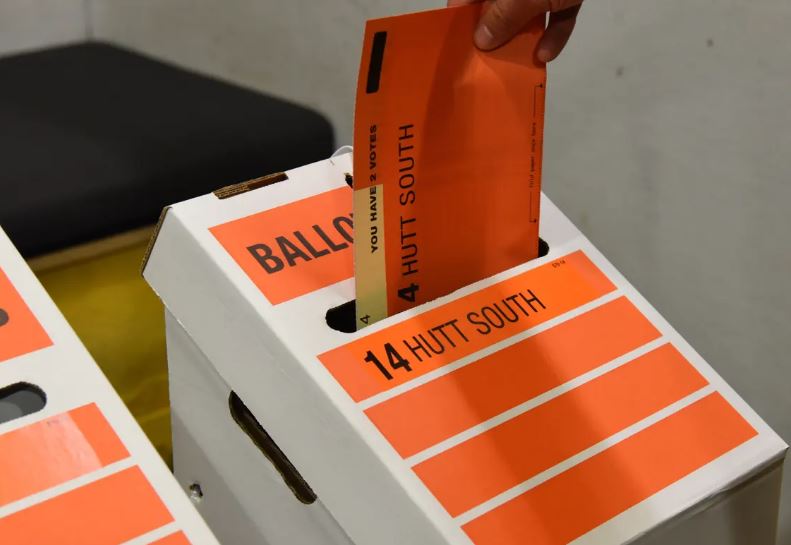

About 1 million of New Zealand’s 3.5 million eligible voters cast their ballot ahead of the 14 October election day. Photograph: Ben McKay/AAP

By the time this editorial goes to print, we will know the outcome of the New Zealand General Election, and that outcome will have been determined by hundreds, if not thousands of voters, who also live and reside in the Cook Islands and overseas, writes Thomas Tarurongo Wynne.

I voted in two New Zealand elections, although I did not reside there, so could still affect and contribute to the democratic outcome of Aotearoa as a citizen of Aotearoa – meeting the criteria of being 18 years or older, having lived in New Zealand for more than 12 months continuously at some time in my life, and being a New Zealand citizen who has been in New Zealand within the last six years.

The criteria after this 2023 election will change to the previous settings of three years for New Zealand citizens and 12 months for New Zealand permanent residents.

In 1965, when the Cook Islands’ constitution and electoral laws were drafted, external voting was considered, but it was not considered an issue for those Cook Islanders who lived abroad, mainly in New Zealand, as the Cook Islands position remains that those who have gone away should not interfere in what goes on at home. This position remains strongly held in the Cook Islands to this day, and it clearly states that you have no say in the affairs of the Cook Islands if you do not live here, do not qualify to vote or be a part of the democratic process, and have not resided here for a minimum of three consecutive months.

But this was not always the case and whether by political persuasion or pragmatism, overseas voting has left an indelible imprint on the politics of the Cook Islands, be it fly in voters in the 1970s, an elected Member of Parliament in the 1990s and overseas voting up until 1998.

My question is, simply this – Is it time to review that position and if so, what could that look like, and if not, why not.

Because be it the legislated requirement of a residency stamp to ensure right of entry, the right to own land, the right to reside, should that not also, with a set of agreed requirements, that do not adversely discriminate, and give all qualified Cook Islanders the opportunity to also vote?

Especially as we enjoy the duality of citizenship and duality of rights of access to two countries, health system, education, and travel, yet only one, allows us the full rights of citizens and that is at its core to vote and be a part of the democratic process.

Looking back, the Cook Islands electoral system had provision for an external seat from 1981 until 2003, and an overseas member was elected at General Elections in 1983, 1989, 1994 and 1999.

In 1998, the Commission of Political Review recommended several changes to the Cook Islands constitution, including reducing the number of parliamentary seats to 17 – that did not include an overseas seat.

At the General Elections in 1999, three of the four political parties fielded candidates for the overseas seat, although an inquiry at the time suggested that the overseas seat cost the Cook Islands public too much with many then wanting it removed.

In 2003, some 2000 voters signed a petition calling not only for abolition of the overseas seat but also for a reduction in the parliamentary term from five years to three, a reduction in the number of MPs and funding for ministerial support.

When the legislature voted in 2003 on whether to abolish the overseas seat, even its incumbent, Dr Joe Williams, agreed to its removal.

Twenty three years on, I raise the question again, for the more than 130,000 off shore, be it our sons and daughters for rugby, league or sports teams, coaching staff, for the Rugby League Aitu taking the field this weekend, millions for halls, churches, and monuments, many will never see or sit under, or the countless tere parties that come through for fundraisers back home, the connection to home runs deep, but not deep enough for many to then ask for the opportunity to vote, or to just broaden the criteria, because the answer from home is a definite no. In that respect you are not a Cook Islander.