‘The Aitutaki secret …’ How canoes evolved (and almost sank) for sailing

Saturday 9 March 2024 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

Two large Aitutaki canoes c. 1900 – one with the outrigger apparently fixed to starboard, fastened together to form a floating platform for cargo (photo – Hocken Collections, University of Otago). 24030836

The design of Cook Islands vaka has changed so much over the years that it’s difficult to speak of a ‘traditional canoe design’ as the Aitutaki canoe demonstrates, writes Rod Dixon.

The design of Cook Islands vaka has changed so much over time that it becomes difficult to speak of a ‘traditional canoe design’. For example, the Aitutaki canoe with the blunt stern, seen by Captain Bligh in 1789, disappeared sometime during the 19th century to be replaced by a very different design by the turn of the 20th century (Haddon and Hornell, 167).

When Te Rangi Hiroa/Sir Peter Buck visited Aitutaki in October 1926 he observed that the hulls of the island’s canoes were now pointed at each end. And whereas the canoe documented by Bligh had only a bow cover or poki, the vaka observed by Hiroa had covers on both bow and stern.

Seats or no’oanga, were lashed to the topsides of the canoes, helping to brace the topsides but now also supporting a mast. A hole in the middle of the seats, at bow and stern, allowed the mast to be secured fore or aft. As Hiroa writes, “The no’oanga then becomes a papatira, from papa, a board, and tira, a mast.”

The reason for the hull pointed at both ends, with covers at bow and stern, and provision for a mast located alternatively fore and aft, stemmed, according to one source, from Aitutaki fishermen’s “preference for sailing as against paddling” to their fishing spots (Haddon and Hornell, 167). And as the outrigger prevented the canoe from ‘coming about’ while tacking, the position of the mast had to be changed from bow to stern or vice versa, (hence the ‘reversible’ canoe design), while keeping the outrigger windward,

If the outrigger were leeward, then as the canoe heeled over under-sail, the float would be pushed under water, capsizing the canoe. But with the outrigger on the windward side, “If the canoe heels over the float comes up out of the water. It adds excitement to sail with the float up in the air and probably the canoe goes faster as there would be less resistance by friction in the water.” (Hiroa, p. 268, 271)

To change direction, the vaka sail was lowered at the end of a tack and the mast shifted to the other end of the canoe which then proceeded stern-first, with the outrigger still windward.

In the early 1950s, on a return journey from Maina motu in an Aitutaki canoe, the American travel writer Willard Price was surprised to see the tu’oe or steersman “untie the jib stay and the side stay, hoist the mast out of its step along with the boom, sails and all, carry the whole outfit to the other end of the boat, re-step the mast, make fast the stays after pounding a nail into the stern with a block of driftwood, fit the end of the heavy fifteen-foot gaff into the peak of the mainsail, and hoist it into place. The whole operation took a good quarter of an hour. … What was the stern was now the bow” (Price, p127).

“It’s the Aitutaki secret,” Willard wrote. “You can’t put on a lot of sail if you have a light outrigger to windward. The outrigger will fly up out of the water and the boat will upset. But a heavy outrigger will hold the boat steady. Our way is to make the float of the heaviest wood we can find, crowd on sail, and trim so that the float rides through the air just clear of the waves.” (Price, p.127-8)

“There comes a time however,” as Te Rangi Hiroa notes, “when the float by rising too high would cause a capsize. It is then, or just before then, that the canoeist leans out on the longitudinal pole to taomi te ama, keep the float down. Hence the longitudinal pole is called the rakau taomi ama - the pole for keeping down the float.”

The “Aitutaki secret” had its limitations as Willard Price found out on his return crossing to Arutanga.

Sailing into a strong head wind, the ama or outrigger float soared, the port-rail sank and the canoe began to take in water. The steersman scrambled forward, loosened the jib, wrapped it around the forestay and grabbed the oar. But the canoe was still carrying too much sail and there were no halyards to take in the sail.

The tu’oe ran forward again, and lowered the fifteen-foot gaff, “a pole so heavy that he nearly toppled overboard along with it, and brought the peak of the sail down, reducing the wind surface by half.” But the vaka was making no headway, so he hoisted the gaff again. The tu’oe now unhooked the steering oar for use as a pole. It stuck between two coral blocks and was jerked out of his hand. As the steersman swam to retrieve it, the canoe was driven steadily towards the reef. Less than fifty feet from the reef, the canoe grounded on a rock and stuck. The steersman jumped in and retrieved the oar. Using it as a pole, he poled the canoe out of danger, until able to sail again.

“Now,” says Price, “the defect of the Aitutaki idea showed up painfully. With an ordinary sailboat, it would have been a simple matter to lay over on the other tack and skim away from the reef. But in this craft the sailing gear would have first to be transferred to the other end, an impossible operation so near the reef and with two passengers in the way.”

The Aitutaki outrigger canoes observed by Te Rangi Hiroa in 1926 varied in length from 4 – 8.5 metres. By this time the old sea voyaging double canoes had disappeared. There remain records of inter-island voyages in double canoes in the 19th century but from almost the first years of missionary encounter, these journeys were increasingly undertaken in European-style boats, including those built by the American beachcomber, Henry Conant, during his residence on Aitutaki in the 1830s. Large outrigger canoes continued to be used as cargo canoes until replaced by clinker boats and whale boats in the first years of the twentieth century.

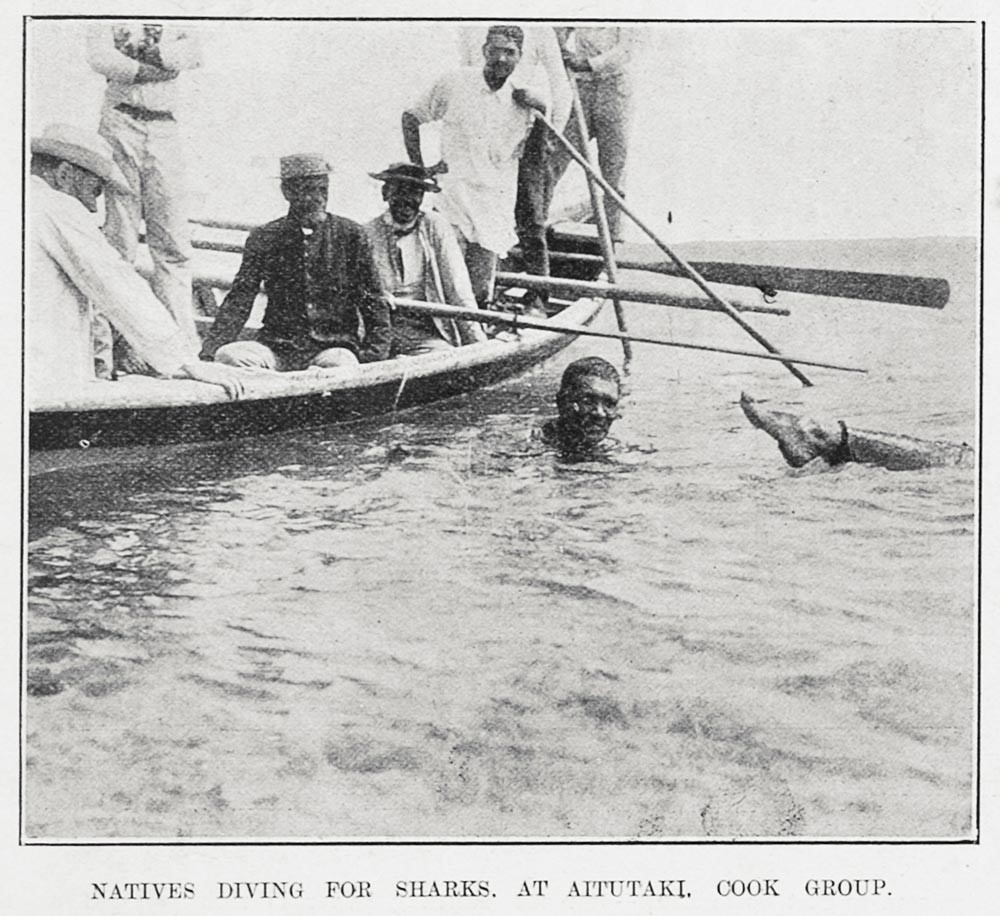

Shark hunting as a tourist attraction (photo - Auckland Weekly News, 25 June 1903)/ 24030837

Shark snaring

Aitutaki’s expansive lagoon is home to the White-tipped Reef-shark and, off-shore, the Grey Reef-shark, the shark most involved in shark incidents.

Since 2012, sharks in Cook Islands waters have been protected from targeted fishing and from the sale of shark products.

Historically however, shark meat was highly valued as a delicacy and in the mid-nineteenth century, it was described by the adventurer William Thomas Pritchard as essential to any Aitutaki feast. Sharks’ fins were also harvested and dried in the sun, and together with local funguses exported to China.

To catch a shark, Pritchard describes two or three Aitutaki men, back in the 1850s, equipped with a supply of bait and a stout rope setting off in a canoe to a spot where sharks were known to congregate, and using the bait to feed them. “Waiting quietly in their canoes, the fishermen soon see the sharks stretching themselves lazily on the sand with their heads just out of the caves formed by the overhanging rocks that rise from the bottom of the lagoon.

“With a noose in the end of the rope which he holds in his hand, a man quietly slips from the canoe into the sea, dives down to a shark, slips the noose over his tail and with a jerk of the rope, he tells the men above the prey is fast. He himself, with a strong spring from the floor, swiftly rises to the surface. All pulling away at the rope together, the shark is soon brought to the water’s edge, and, as the tail is raised out of the sea, the shark becomes almost helpless; then with a strong pull together, is suddenly bounced into the canoe.

“Frequently as the shark lies at the mouth of the cave, with only his head out, the tail cannot be reached. The diver then has to tap the monster gently on the head, who, lazy and drowsy after the good feed just supplied, quietly turns his tail to the intruder who slips the noose before he knows it.”

A blow from an axe between the eyes ends the shark’s life.

Shark-catching on Aitutaki continued well into modern times. In November 1937, the Pacific Islands Monthly reported an Aitutaki shark catcher called Terongo, aged 21, who encountered an 8-foot (2.4 metre) shark in the lagoon.

“Passing in front of the youth, the shark took a savage lunge, removing at one bite a portion of the boy’s upper arm. Meanwhile, two other fishermen having come to his assistance, all three managed to scramble on to the reef. The water in their wake was deeply stained, and excited by the blood, the shark pursued them to the edge of the coral. Three miles from the village, Terongo lost consciousness long before his companions, paddling furiously, could reach the settlement. There, one of the Suva trained native medical practitioners was able not only to save his life but to make such a good job that there is every possibility of Terongo regaining the partial use of his arm.”

References

A.C. Haddell and James Hornell, 1975, Canoes of Oceania, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu

Te Rangi Hiroa/Sir Peter Buck, 1927, Material Culture of the Cook Islands (Aitutaki)

Willard Price, 1956, Adventures in Paradise, Heinemann,

William Thomas Pritchard, 1866, Polynesian Reminiscences; or, Life in the South Pacific Islands. London: Chapman and Hall