What is our excuse for the loss of our language and cultural values?

Saturday 30 July 2022 | Written by Supplied | Published in Features, Weekend

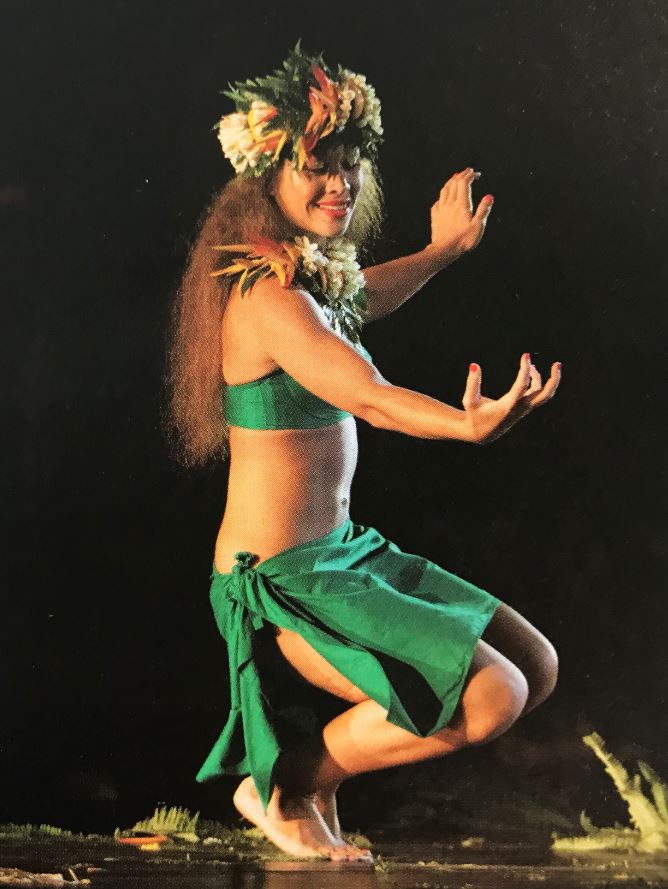

A female dancer performs at Heiva 2016 event. Photo: MATAREVA/22072928

Curator and manager of the Cook Islands Library and Museum, Jean Tekura Mason recently returned from Tahiti where she attended the country’s 141st Heiva.

She compares the event with Cook Islands’ Te Maeva Nui which started yesterday with the float parade.

As we approach the annual Te Maeva Nui celebrations our cousins in Tahiti have just finished theirs, its 141st Heiva. Hei means to assemble and va means community space. Started in 1881, the festival was originally organised around celebrating the national day of France, Bastille Day, but since 1985 it has come to be associated more with celebrating the people and culture of Tahiti and her islands although it continues to be held around 14 July. Formerly called Tiurai (from the English word July), the name was changed to reflect Tahiti’s political autonomy from France. While colourful there are sobering aspects to the performances some of which focused on the loss of the Maohi language and culture, with some orero (spoken poetry) being openly critical of the French influence. As here, even the interest in the performing arts is diminishing, particularly among the men but they can blame the French whereas we here in the Cook Islands can only blame ourselves.

But for all that the Heiva remains a spectacle well worth attending.

Thanks to Air Rarotonga we were able to attend the closing night of the Heiva festival in Tahiti held at Tahua To’ata in Papeete on Saturday 16th July 2022. The festival, which includes traditional sports as well as an arts and crafts expo, usually runs for about two weeks and the three best teams of the competition perform on the final night. This year’s festival was a bit special because there had been an hiatus over the past two years due to the Covid pandemic and the tourists are back so it was well attended this year.

While our Te Maeva Nui performances are held in a closed auditorium, in Tahiti the Heiva dances are performed in an open-air stadium. Being geographically further north, Tahiti’s weather is warmer than here. There is an elevated, covered theatre stage at the back, which is for the band and singers only. Like here, there is no photography or filming permitted, except for the Heiva’s own crew. There is no advertising either to ruin the appearance of the performances either on film, or in real life. There is not a banner, poster nor advert on a giant screen to be seen. The focus is entirely on Maohi culture.

It is an amphitheatre with the dancers, troupes of a 100 or more, in the centre, often with girls out-numbering the boys. For most performances the vocals were left to those on the elevated stage. This is unsurprising because the dances are fast and vigorous, often with quick changes of costumes in between. A well-appointed band does all the singing and the numerous drummers provide the accompaniment of musical instruments. Bands can comprise up to seven drummers on pahu (pa’u mangō), three tari parau (bass drums; pa’u) and the rest on four or five to’ere (wooden drums) accompanied by seven singers, one of whom might play the vivo (nose flute) and others on guitar when the performance requires it. By comparison Cook Islands bands are smaller in size, often with just one pa’u and one or two pa’u mangō. The skilful use of the large number of pahu was particularly striking. The overall sound produced is resonating and powerful.

There is less chit chat by the officials and narrators. In fact, there are no special reserved seats for government officials. Everyone in the audience is equal here. Narration for a troupe is done only once, at the start of their performance, and is spoken in French, Tahitian and English, to accommodate the large number of tourists that attend. Individual items do not get narrated. Each troupe has its own theme and performs its whole repertoire in one night, in one and half hours, in a programme that goes roughly like this: a spoken piece (poetry or soliloquy called orero) by the troupe ra’atira, usually an older man or woman; a combined drum dance by males and females; an imene tarava (similar to our imene tuki but with less ‘tuki’ grunts); an ute paripari (performed by a male and female duo with a backup band, unlike our large groups of 30 or more people on stage); and then a solo performance by the best female dancer of the troupe, followed by the best male dancer; then the whole group appears in an action song (aparima); or it might be males only; the girls coming in later; then there’s a couple of symphony of drums performances; then the entire troupe returns in a large circle, chant-singing, interspersed with a drum dance, which is similar to our ura piani. The categories are labelled thus: orero, hura ava tau; hura tau; pupu himene, tarava Tahiti, tarava Raromata’i; and tarava Tuha’a Pae. As for each male and female dancer candidate put forward by each troupe, they must wear simple costumes: a maro itiki (tied loincloth) for the boy, and a short plain pareu cloth (with no adornments on the hips) for the girl. This is so the judges can see their talents clearly.

First up is Fetia Ori Hei, who perform an action song about the killing of Hono’ura’s turtle (Onokura, a legendary character also known in the Cook Islands). After them is Nuna’a Rurutu, followed by Hana Pupu Oraand then Tamarii Teahupo’ocome on for a himene tarava. But the best is kept to last - Hei Tahiti, - the overall winner of this year’s Heiva. Their theme, “What is Mana?” The narrator described it as being a mysterious power or force that was present in all things and the gods wielded it also – that the ancients were very aware of this power, force and authority. That it protected the ancient Maohi from evil, illness, bad luck and sorcery. The dance team males perform briefly, in yellow rauti skirt and green rauti headdress. The ra’atira appears on stage; a solo dancer remains on stage while the rest exit. During the solo dance five people emerge who represent the main gods of ancient Tahiti.

There’s an action song where the girls outnumber the boys two to one so they perform in small groups of three; the male is situated between two girls. It is a dance about love. The solo male dancer sits down on the floor at the front of the stage, back to audience, while the whole troupe performs in front of him. The lead female dancer makes overtures to him. He sits there seemingly enjoying himself. Now and then he gets up to dance with the lead dancer, who wears a slightly different costume from the rest of the women. Meanwhile, all around them the other dancers perform as in a menage a trois. It is one of the most explicit dances I have ever seen about the subject of love but the story is told with beauty and truth.

The best poetry is saved for last. The female ra’atira in white robes and tall yellow headdress asks the question, “O vai te mana i teie tau”? Who is in charge today? “Tahiti e, Tahiti e, e āra” she calls out, all the while the drums are sounding gently in the background. The ra’atira exhorts the people to wake up and be aware of the threats coming to them from across the sea. Then the full troupe returns to the stage, boys in red and girls in white for action song. There is a dramatic finish with the cry from the whole troupe: “E Tahiti e”, to which the audience replies, “Ou” (yes).

Tiare Trompette, the troupe’s manager-owner, is called up to the stage where she proceeds to thank her dancers, costume designers, choreographers, composers, etc. Apparently, according to another Cook Islander also at the Heiva, one of the dancers in this team is a Cook Islander from New Zealand by the name of Rose Tunui.

A fantastic night was had by all of us. Hei Tahiti presented the most moving performance. The Hei Tahiti ra’atira exhorted the population to be strong in the face of the losses of their culture and language. It made me reflect on what is going on here. We’re not under the control of a colonial power so what is our excuse for the loss of our language and cultural values?

Jean Tekura Mason, Ngati Nurau and Ngati Teakatauira of Atiu and Mauke, mixed with Scottish (Ngati Turner Lamont) and English (Ngati Geordie), is the curator and manager of the Cook Islands Library and Museum.