Manuae, Penthouse magazine and a sunken Aussie grader

Saturday 19 February 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

Air Raro Cessna 337. Pictured: EWAN SMITH/ 22021822

Over a period of two months in 1981, a group from Rarotonga cleared and constructed a 4000-foot airstrip on Manuae island.

A crucial piece of equipment for clearing the airstrip was a grader provided by the Australian Government for the Northern Group Airstrip Programme.

Unknown to the Australians, it had been temporarily diverted to Manuae.

In 1980, the lease of Manuae island was purchased by the Manuae Holdings Company (MHC), a group of Manuae landowners and others based on Aitutaki. Just before Christmas, 1980, the new MHC plantation manager Boy Mitchell arrived on Manuae with his family. MHC planned to maintain the existing copra plantation while also exploring other development opportunities for the island.

These included harvesting the lagoon’s marine resources for fresh fish exports to Rarotonga, and later, plans for the development of a $90 million international hotel and casino.

Both developments required air access. So, early in 1981, the Minister for Trade, Labour and Transport (TLT), Hon. Vincent Ingram despatched William Ahiao, a TLT engineer to Manuae with his wife and children, including two grown up daughters and their husbands. They were joined by a seven-member TLT crew, a work group from Aitutaki and a several prisoners serving out prison sentences on the island.

Over a period of two months in 1981, this group cleared and constructed a 4000-foot airstrip – slightly shorter than Aitutaki’s wartime coral strip – surfacing it with compacted coral drawn from Manuae lagoon. A small kikau terminal was built, equipped with three flush toilets. A windsock indicated wind-direction and, in the absence of landing lights, the runway was marked out with palm fronds.

A crucial piece of equipment for clearing the airstrip was a grader provided by the Australian Government for the Northern Group Airstrip Programme. Unknown to the Australians, it had been temporarily diverted to Manuae by the Minister for TLT.

When the airstrip was ready for operations, I flew with Vince Ingram on the 90-minute flight by Air Raro Cessna 337, piloted by Ewan Smith, for the official opening.

On the ground, the ‘opening ceremony’ was quickly completed. Before climbing back aboard the aircraft, the Minister made it clear to William Ahiao that he wanted the grader back in Rarotonga before the Australians noticed it was missing.

The grader and bulldozer drivers spent the remaining hours of daylight re-compacting the airstrip, while the rest of the TLT crew went off to check their fish traps.

With a little time to spare, I walked along the avenues of coconut trees, laid out in straight rows, and made a quick map of the plantation compound (labelled Vai Toka in my notes). The compound comprised two large copra sheds, fronted by drying racks, a copra kiln and shed, a boat house near the reef passage, a group of workers’ houses and outhouses, a kitchen house, a metal workshop, and a partially underground water tank or ‘well’ fed by rainwater. The buildings were shaded by a grove of breadfruit and lemon trees. Nearby was a large, full size concrete tennis court. And at the end of the settlement, away from the workers’ camp, was the manager’s house, surrounded by verandahs, now boarded up.

The following day, the TLT crew set to work on lightering the grader through the reef to the Manuvai, which had arrived overnight with Bruce Graham and a fresh group of prisoners.

Getting in and out of Manuae by sea meant negotiating a reef passage on the north-west of the island, close by the village. This passage has a dog leg at the entrance, which meant boats entering the passage on a favourable wave, had to turn and run horizontally across incoming waves before turning again into the final leg of the channel. More often than not, boats flipped mid channel, throwing their passengers into the sea, with the added danger of being thrown against the reef.

To bypass the dog leg, the TLT team had blown a new channel a few hundred yards away. This involved William Ahiao and his crew laying a number of World War II bombs at strategic points on the reef flat; lighting the 50 second fuse with a cigarette; then legging it back to the beach under a rain of coral debris. The end-result was a channel 30 feet long, 15 feet wide and 20 feet deep.

Once the channel was ready, the Australian grader was driven up a ramp onto a platform laid across two old Union Steamship lighters lashed securely together. At 4.15 pm, the barge O Rongo, standing off, began hauling the lighters out to sea through the new passage. “A1 meitaki,” I heard Bruce Graham saying.

Then, as the lighters met the open sea, a large wave came rolling in. The port lighter lurched to the left, smacked the reef, and began taking on water. The crew scrambled from port to starboard, as the left-hand lighter sank and the right-hand lighter rose high in the air, rolled over, and jettisoned everyone into the sea. Some of the crew didn’t have time to jump clear, including William Ahio’s young son, and went down with the lighters. In less than a minute, all that could be seen above water was the grader’s exhaust pipe. Then, that too was gone.

Everyone’s attention went instinctively into rescuing the people trapped in the lighters. Somehow, they were freed and popped back up to the surface, gasping for air. An aluminum dingy raced out to their rescue. On its way back, via the dog leg, it was caught by a wave and flipped, dumping the survivors into the sea, injuring one badly. To avoid a repeat, the rest of the crew were picked up in the open sea and taken straight out to the Manuvai.

In the remaining hours of daylight, the Manuvai’s slings were put to use. Bruce Graham’s team, using scuba gear, attached lines to one of the lighters that had broken free underwater. Within half an hour it had been hoisted aboard Manuvai. Plans to recover the grader were left to the following day.

Next morning, it was clear the grader couldn’t be recovered with the equipment available.

Bruce decided to return to Rarotonga on the Manuvai with the rescued crew, plus two prisoners who had completed their sentences. I decided to join them. There remained only the hazardous business of getting through the dog leg. I threw a couple of glass floats into the dinghy, reassuring myself they could be useful if we flipped.

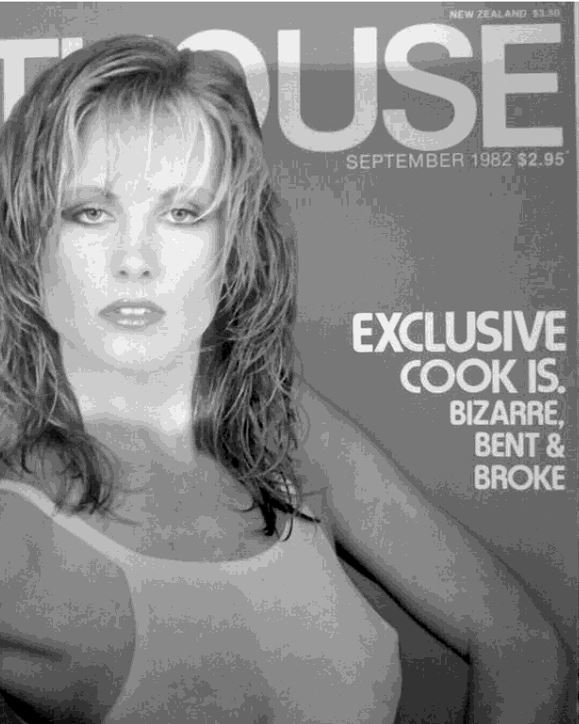

A year later, the sunken grader became news in Australia. Penthouse magazine splashed its September 1982 edition with the headline “Cook Islands – Bizarre, Bent and Broke”. Inside was an article entitled “Plundering Paradise” written under the pen-name ‘William Royal’ (Prince William had been born a few months previously).

The article alleged extensive corruption by the government of Sir Tom Davis and cited the diversion of the Australian grader to Manuae – “now lying in 10 fathoms of water” – as a prime example of the Government’s ‘waste’ of foreign aid.

Vincent Ingram responded in Pacific Islands Monthly (November, 1982). According to the Minister, the author of the Penthouse article ‘William Royal’ was, in fact, Richard McDonald, a former Cook Islands Director of Auditing who had been deported after making claims of fraud against successive Cook Islands governments.

“Although it is true to say,” wrote the Minister “that the grader was originally supplied for the construction of air-strips in the northern group, delays in launching the airstrip programme … meant that the grader was available for the construction of a strip on Manuae.”

“The grader was lost overboard in rough seas while being returned to Rarotonga. It has since been recovered and is now back at Rarotonga. The Australian Government were advised of the mishap and the Australian High Commissioner in New Zealand, who was in Rarotonga recently, has inspected it. It will be repaired and put back into use. It is not ‘now lying in 10 fathoms of water’”, Ingram wrote.

Thirty-seven years later, Neil Mitchell Senior, updated the story. Neil has visited Manuae four times, the first time in 1977. Then again in the 1990s. Writing on Air Rarotonga’s Facebook page, he reported the airstrip was “long overgrown”. He’d even heard that an Aitutaki man had planted coconut trees on the runway “as, he said, making this place accessible by plane would kill its beauty”. The full-sized concrete tennis court, built by former manager Karlo Andersen, was still there. “Last time I saw it you could have had a game on it as was still in good nick.” The sunken well still provided “chilled fresh water, not unlike that bottled Evian stuff”.

And the grader? – “Outside the passage in 30 metres of water. Dived on it a couple of times and have a photo of it, sitting in 30 metres. A spooky sight!”

I contacted Neil, wondering how the grader could be under water in Manuae and back in Rarotonga at the same time?

Neil told me that the main frame of the grader had been salvaged by Bruce George. This must have been ‘the grader’ the Australian High Commissioner inspected. But, Neil told me, the sea floor outside the reef passage remains littered with large parts of the grader.

Greg Wilson agreed. Greg had been involved in efforts to recover the grader while working for Marine Construction (Don Dorrell). “Most of the grader,” Greg recalls, “remains on the bottom in Manuae.”

The frame that was sent to Rarotonga was later buried on the beach in front of the old Public Works Department in Arorangi. “I’ve seen that personally,” Neil told me. “There was a huge rubbish pit or hole close to the beach. Everything went in there!”

“To cut a long story short, the grader was never put back into commission, ever again”

And to prove it, Greg still has the ignition key, somewhere.