Karlo Andersen ‘King’ of Manuae

Saturday 5 February 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

In the 1950s, Karlo Andersen ran Manuae like a military barracks. “For a man with a notion to play god, the set-up was ideal.”

Manuae island’s copra plantation had many managers over the years including, for five years in the 1920s, Captain Andy Thompson, legendary skipper of the schooners Tagua, Tiare Taporo and Charlotte Donald. But one of the islands most successful and colourful managers was Karlo Andersen, an émigré engineer from Denmark.

Karlo Andreas Andersen was born on 21 September 1894, in Grenå, on the Jutland Peninsula of Denmark, the youngest of five children born to Peter Marthinus Andersen, a restaurateur and his wife Anna Karoline Vilhelmine Moller.

Karlo arrived in Auckland from Southampton on the eve of the second World War, telling a reporter from the Auckland Star (20 April 1939) that he’d left Denmark because he was unable to expand his engineering business in Copenhagen, because of drastic regulations imposed by the Danish Government.

He had decided instead to settle in Rarotonga for a few years. “I may try to develop my business from there,” he said. “Fortunately, however, I have enough money to live comfortably without worrying.”

Asked about the likelihood of war in Europe, Andersen said, “there was little danger of Nazi violence being used against Denmark.” (A year later, the Nazis invaded and occupied the country). He added that he thought “Hitler was the best man available as far as the German people were concerned”. For all that, he did not think his influence should extend beyond the borders of his own country, the Auckland Star reported.

In 1946, after several years on Rarotonga, Karlo applied for the job of manager of the Manuae copra plantation. The lease had recently been purchased by William Buckland of Melbourne and the new owner wanted to modernise. Local agents A.B. Donald decided Karlo – “with his impressive qualifications and a staggering capacity for work” – was the man for the job.

“Karlo came in like a tornado,” wrote author and Cook Islands politician, Julian Dashwood. “Old style trays for sun-drying the copra were replaced by a fifteen-thousand-dollar diesel dryer.” A generator was installed to electrify the island, some three decades before the remaining outer islands obtained power. Years later, the same generator stood “as clean and brightly painted as the day it was unpacked” (Forbes; 90).

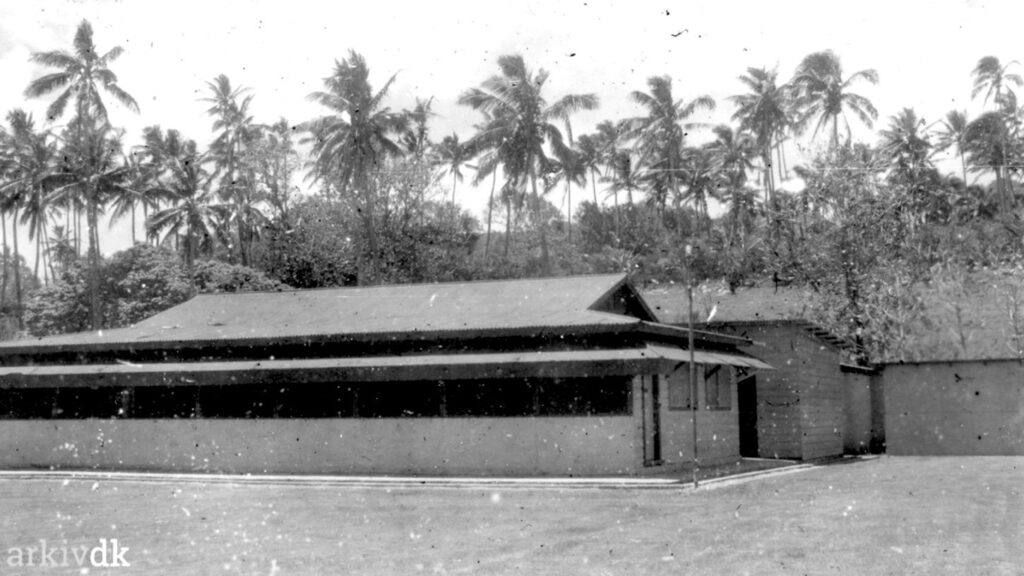

Karlo set about building or improving administration and living quarters for the manager and labourers, a store, a blacksmith and fitting shop, a boat-building shed, and a tool shop. Ian Forbes, who visited the island in the mid 1950s, noticed the workshop was “equipped with every tool imaginable, all neatly displayed on a wall where each tool was marked out in paint and not one item was missing or out of place” (Forbes; 90).

Karlo also set up a hospital with an operating table, a dispensary and a dental clinic equipped with a real dentist’s chair. And a school for the worker’s children in which he taught.

He also built a radio-telephone for daily radio checks using equipment salvaged from the wreck of the MVAlexander in 1951.

The Manuae copra plantation was self-sown, with the trees densely packed and all the usual mess of undergrowth. The resulting chaos offended Karlo’s sense of order. He arranged for a large percentage of the trees to be cut down and the undergrowth cleared. The plantation was replanted with the trees in straight rows following the lines of newly built coral paths, running at right angles to each other.

The outcome, according to Ian Forbes, was that Manuae had all the appearance of a well-ordered city-park – “very well maintained, especially on the ground beneath the coconut palms. Not a single weed to be seen. It was indeed an eye-opener to see such perfection in cocoanut management.”

The estate roads, lined with whitewashed coral stones, “were perfectly formed and free of weeds and meticulously sign-posted”. Driving around the plantation with Karlo at the wheel of the island’s only vehicle, Forbes observed that, upon reaching an intersection – “Karlo would signal that he was going to stop, then pull up, look both ways. And only when he was satisfied that the way ahead was clear, would he continue on.”

A launch based at Manuae carried workers across the lagoon to camps at Mata’ara and Arikirauru on the twin islet Te Au o Tu where copra was also harvested. Andersen’s concern for order could be seen here too with – “timber stakes with bright reflective metal markers mark(ing) a safe passage through the lagoon’s coral outcrops”. (Forbes; 91).

Karlo oversaw a workforce of around 30 men, mainly from Palmerston Island, employed on three-year contracts. Married men were often accompanied by their wives and children. A wire fence separated single from married quarters. “The penalty for being caught on the wrong side of the fence was fifteen dollars ($15) and termination of a man’s contract.”

The single-men’s quarters “occupied a barracks with rows of beds on which their blankets hung at identical distances from the ground and each man’s kit was assigned a special place on the shelf above his head”. (Dashwood; 256).

Alcohol was banned. Andy Thompson recalled the time a Public Works official smuggled a bottle of Johnny Walker ashore in a towel. “Karlo guessed as much … and had it out in a jiffy. They were standing beside a palm and he held the bottle by its neck, swinging it gently, while the public works fellow watched on. Then he swung it a bit harder and the next thing, whisky was running down the palm trunk into the sand and Karlo was holding a few inches of jagged glass in his hand. A man who does a thing like that is just a bastard in my opinion,” said Andy. “So why didn’t the official take a swing at him,” he was asked? “Wait till you see Karlo,” Andy replied, “You could bounce cannon balls off his chest.”

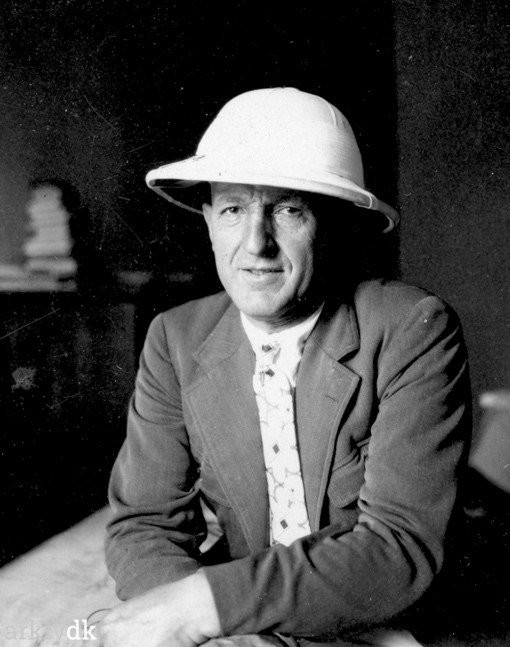

Karlo was always immaculately dressed in white cotton ducks and a solar topee, his tie tightly fastened with the tie-blade tucked firmly into his belt. As Forbes observed: “His immaculate tropical dress would outshine any English plantation master in India.” And like any colonial agent, Karlo regarded himself master of everything happening on ‘his’ island.

This meant that every aspect of the plantation workers’ daily life was regimented. From morning to night, a “public address system blared dance music and staccato orders” from the manager (Dashwood; 256).

Ian Forbes recalled being awakened at 7am – after a heavy night of illicit drinking – by classical musical blaring from loud-speakers attached to poles around the compound. “This was reveille” for the copra workers.

Thereafter, “a police whistle was used to get the attention of the workers – one whistle call for each overseer or foreman. Failure to acknowledge this summons in haste was foolhardy indeed” and resulted in the loss of wages (Forbes; 92).

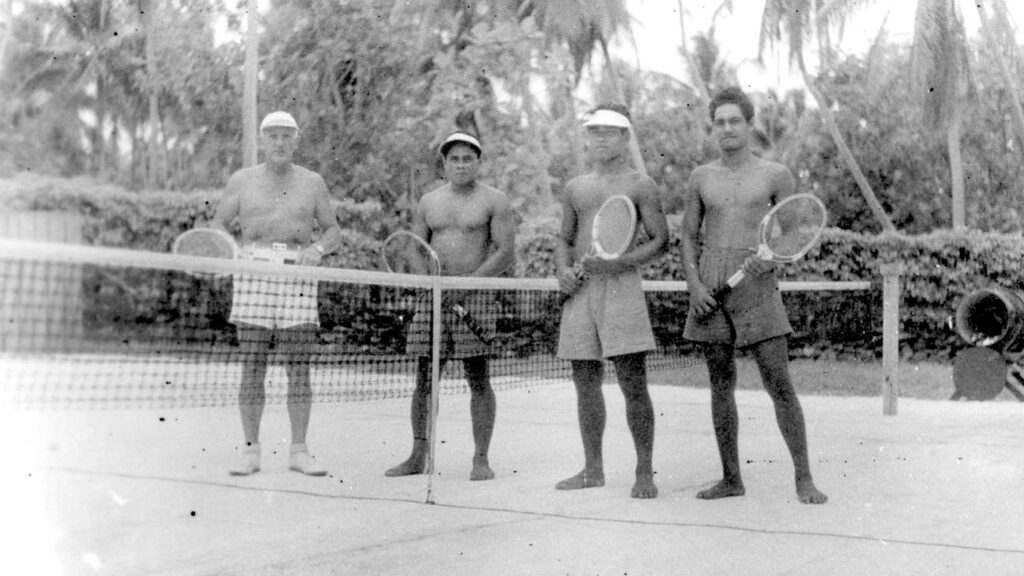

To ensure his workforce stayed fit, Andersen built a concrete tennis court inside the compound. It cost $2400 but Karlo considered it worth every penny. “It develops a team spirit,” he said, “and keeps their minds off other things. I expect everyone who isn’t sick to turn out after work. Shower, clean shorts, and an hour on the courts. They’d only get into mischief sitting around, twanging a guitar and thinking of women. Anyway they like it. It’s a regular thing for the Manuae boys to clean up the singles and doubles championships when they go back to Rarotonga” (Dashwood; 258).

The everyday harvesting of coconuts was forbidden, even drinking nuts. Instead, a ration of dried coconut was issued to every worker once a week. Fishing was also prohibited except on Saturdays. The catching of seabirds and the taking of eggs was forbidden, at all times. “The same went for fish and other seafood except as he directed. He was a serious conservationist” (Forbes; 91).

“Thinking that all this spit-and-polish discipline must run counter to the easy-going island temperament,” Julian Dashwood asked Karlo “Do you have trouble recruiting your men?”

“Most of the boys you see here are second-termers,” Karlo replied. “And there are always more applicants than vacancies. You know why they like it? Because they know just where they stand from the minute they get up until the lights go out. If they break a rule, they know what it’ll cost them. I never lie to them and they know it…”

The harsh conditions imposed by Karlo were partially offset by a benign paternalism – “from midwifery to the care of (people’s) teeth, the amount and type of food a person may or may not eat, how it should be cooked and by whom, when to work and when to sleep…..Karlo was doctor, dentist, midwife, dietician, mechanical engineer, radio-operator, electrician, school teacher and plantation manager” (Forbes; 90).

No one has recorded what the copra workers thought of Karlo’s regime. But reading Moana Moeka’a’s recent book on work conditions at Makatea Island during exactly the same era, it’s debatable which regime was harsher. Yet the workers returned.

Karlo had big plans for Manuae but they weren’t shared by his Australian boss, William Buckland. He decided to replace Karlo with a Rarotongan manager. “This was the moment,” Dashwood recalls, “when the Manuae men might have been expected to welcome the newcomer with enthusiasm. Karlo at first refused to allow anybody to land, but finally let the (A. B. Donald) agent ashore”.

“The upshot was that the entire labour force declared its intention of accompanying Karlo, leaving the island to run itself. There were no ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’, the agent could take it or leave it, and he preferred to leave it.”

Karlo was reappointed manager in June 1958 (PIM, 1 June, 1958). He remained on Manuae for a few more years, retiring when the lease was acquired by the Manuae Development Cooperative Society.

He returned to Rarotonga, to his home in Vaima’anga. There, he earned a living repairing radios and other electrical equipment.

According to his friend Ian Forbes, Karlo also established himself as “a quack with magical electronic cures for all sorts of ailments” – one of which almost killed Dashwood, then a cabinet minister.

Among Karlo’s personal treasures – including his topee and Volkswagen Beetle – were a gun collection, Sevres tableware, silverware engraved with the Danish Royal insignia, a morning coat and a silk top hat. He began to sell off his gun collection, sensing his time was nearing. He died at Vaima’anga on 23 April, 1974, aged 80, and is survived by two daughters Lucy and Marina and his partner Nooke Ravengakore.

References

The above account relies heavily on the following sources -

Julian Dashwood, 1964, Today is Forever, Doubleday and Co, New York

Ian Forbes, 2003,Pap'as in Polynesia - Tom Neale and other Cook Island characters, Netpress Printing Solutions

aitutakigarden.com