Mangaia’s great vaccine experiment of 1866

Saturday 16 October 2021 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Memory Lane

Reverend William Wyatt Gill with a local Mangaian team vaccinated the entire population against smallpox in 1866. 21101537

The story of how Davida Numangatini’s abduction into slavery in Peru led to Mangaia’s great vaccine experiment of 1866.

On Sunday, 25 January, 1863, a ship, believed to be the missionary ship “John Williams” stood off Mangaia. A canoe put out from shore, paddled by eight young Mangaians. Approaching the ship, they realised their mistake but were reassured when the ship’s captain told them they were American whalers come to trade for provisions. Five of the young Mangaians clambered aboard. They were drugged with brandy laced with opium and imprisoned in the ship’s hold. The vessel made sail, bound for Atiu, Rapa and Peru (Sydney Morning Herald, 13 October, 1863).

The “pa'i keia tangata” was the frigate Empresa de Lima, owned by Don Francisco Carnavare of Lima, Peru; the drugged spirits were administered by the ship’s surgeon, a sinister man called Dr. Inglehart. The ship’s master was Captain Enrique Detert. The ship’s mate was J. T. Browne who joined the Empresa at Caroline Islandat the same time as George William Ellis, who opposed the kidnappings, left the ship. (Ellis later became a trader at Tongareva and Manihiki – Moss, 1889;105, Maude 1981; 37).

The kidnapped Mangaians were “Davida, an ariki, the son of the Ariki Numangatini; Teao, also an ariki, Ruringa and Tangiri, members of the ‘ekalesia, and Kurikino (‘e tangata ‘ua ’ia, ki’ire ona ‘e tao’onga).” (Letter from Numangatini ariki to the NZ Governor Grey).

Raids such as this, by Peruvian barques, brigs and schooners were frequent across Polynesia in the years 1861-63. After the abolition of African slavery, Peruvian entrepreneurs experienced a shortage of workers for the country’s silver mines, guano islands and rice and sugar cane plantations, and turned to the Pacific Islands as a source of cheap labour.

Peruvian businesses were issued government licences to import Polynesian workers ostensibly under voluntary labour contracts. The result was a flotilla of ships, sailing for the islands, equipped with tiers of bunks in their holds, iron grills on their hatches and heavily armed crews.

The kidnapping of Davida, the son and heir of the ariki Numangatini led to urgent correspondence between the Mangaian missionary Reverend W. Wyatt Gill, the Governor of New Zealand, George Grey and Lord John Russell, the British Foreign Secretary.

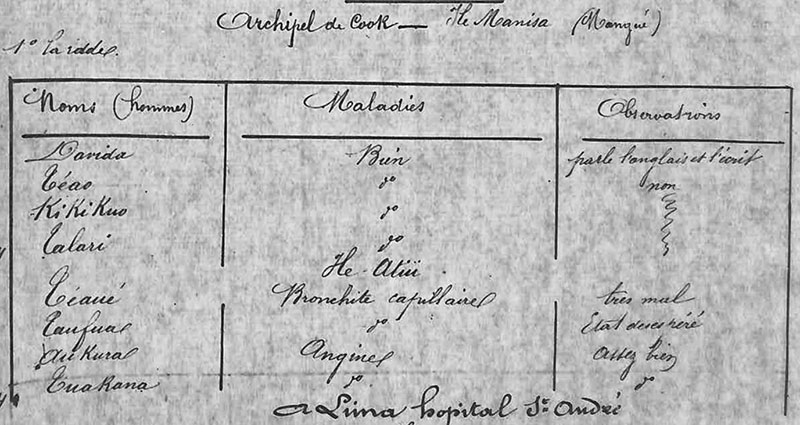

Medical Report from the Hospice St Andre in Lima Perus on Polynesian Islanders listing 8 Cook Islanders including the four surviving Mangaians - Davida, Teao, Kurikino, and Tangiri – and seventeen Tongarevans. 21101535

While the British exchanged letters, the Commandant of the Imperial Commissary of France in Tahiti, Monsieur E. G. de la Richerie took action, dispatching French naval vessels to chase down and seize slave ships, to prosecute and imprison their masters and to free and repatriate their slaves. In 1863 there were six confiscated Peruvian slave ships impounded in Papeete harbour awaiting disposal.

In April 1863, Commandant de la Richerie despatched a warship, the Latouche-Treville from Papeete to Mangaia where the ship’s captain Lieutenant C. de Saint Sernin met with Numangatini ariki and the missionary Rev. Wyatt Gill. He then sailed for Atiu where, prior to the Empresa’s visit, five Atiuans, including the “Chief Governor’s son” had been kidnapped by the Rosa Patricia.

On Atiu, “the ariki asked (Captain de Saint Sernin) to take two islanders to ... Peru in an attempt to find the lost Atiuans and Mangaians and arrange for their return.” Atiuan delegates were sent to Peru on the French schooner Favorite where they joined a Marquesan interpreter Hoki who was assisting French authorities rescue the abducted islanders.

Meanwhile, after three months at sea, the slave ship Empresa de Lima with its human cargo including the five abducted Mangaians and a young Atiuan, arrived off Callao, the port city of Lima, Peru.

There, Captain Detert discovered the Peruvian government, under international pressure, had issued new regulations, outlawing the slave trade. At the request of British and French authorities, orders had also been issued for Detert’s arrest and for the detention of the Empresa.

Standing off Callao, overnight, the Empresa clandestinely transferred Davida and his companions to a coastal schooner, the Paquete de Huacho, taking them 90 miles north to the small port town of Huacho. Fearing his own arrest, Detert put the captives ashore and abandoned them to their fate. They were immediately rounded up by armed men and put to work in local rice and sugar cane plantations.

Meanwhile, in Lima, the French charge d’affaires hearing of the Empresa’s detour to Huacho, organised a rescue party led by a French engineer M. Eucher Henry, accompanied by a French naval surgeon Dr. Chirurgien Bon, the Marquesan interpreter Hoki, and an escort party of Peruvian police and cavalrymen.

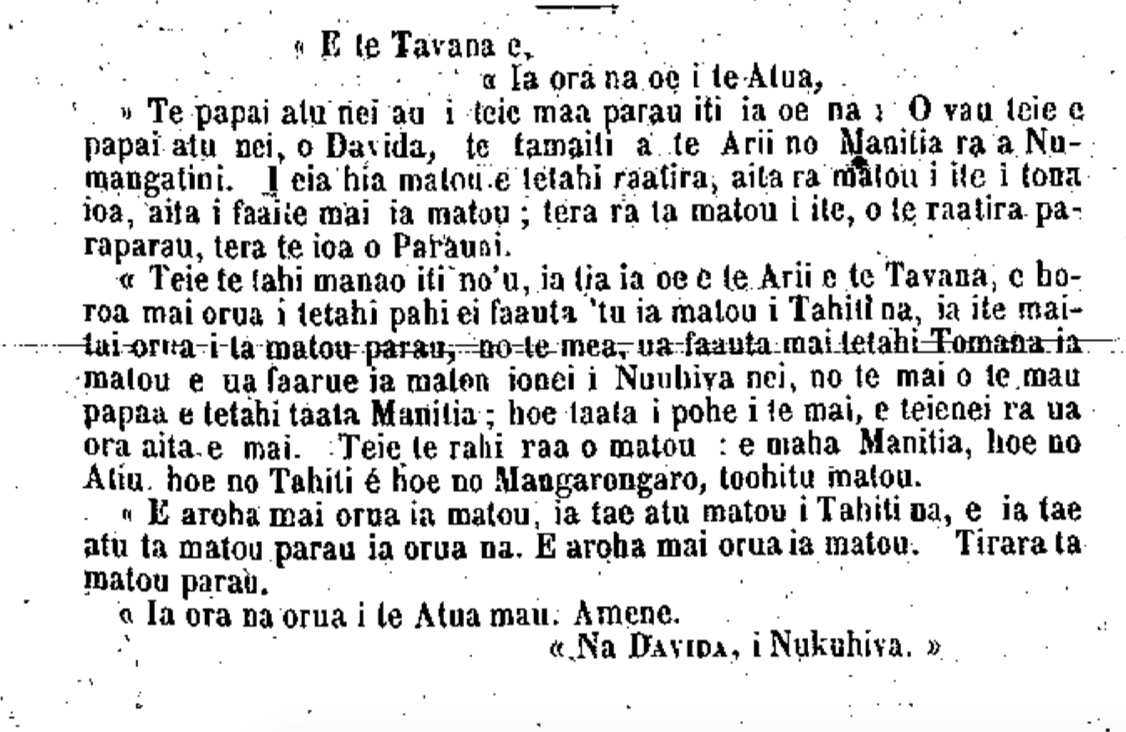

Davida’s letter to the Governor of Tahiti seeking repatriation for himself and his comrades– Messager de Tahiti 10 October, 1863. 21101536

Heading north, they found the islanders scarcely alive, reduced by their sea-journey and ill-treatment to “human skeletons dried up by hunger, illness, running sores and abuse.” Many bore signs of beating and scars from whipping. But despite their suffering, Dr. Bon reported “What smiles one saw when the name of their island was suddenly mentioned; and on the wan, emaciated faces, barely human, what rays of unspeakable joy!”

Those whom the French managed to save, including Davida, were taken back to Callao and placed under French protection. During this time, Ruringa, one of the five Mangaians died. In Lima, medical checks were carried out on the remaining survivors at the hospices of St Andre and St Anne.

The ‘Medical Report on Polynesian Islanders’ lists the names of the four surviving Mangaians – Davida, Teao, Kurikino, and Tangiri whose medical condition was reported as good and four Atiuans, two of whom were in poor condition with capillary bronchitis and two of whom were recovering despite underlying cases of angina. The names of eight Tongareva men including two who were too ill to leave hospital and nine Tongareva women (of whom six were well, and three in extreme suffering) were also listed.

Captain Detert and his crew had been arrested and Davida Numangatini had given testimony against his abductors to the Peruvian Judge of Crime. Detert was convicted and sentenced to six years imprisonment.

Following Detert’s trial, the six surviving captives from the Empresa – Davida, three other Mangaians, one Atiuan and a Tongarevan together with 23 other captives seeking French protection (a total of 18 men and 11 women) were placed on board the French warship Diamant, which set sail for Tahiti on 20 July, 1863.

Three months earlier, the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio had urged “all landowners who have obtained Polynesians for their haciendas … to vaccinate them because the smallpox wrecks havoc among the unfortunates.”

Unfortunately none of those on board the Diament had been vaccinated. While still at sea, 14 died of the virus. The surviving 15 reached Nukuhiva on 20 August, 1863. At Taioha’e they were quarantined and looked after by Roman Catholic missionaries.

The bell at Mauke Zion Church was a gift to Maukean Teveta, from Davida Numangatini of Mangaia. COOK ISLANDS TOURISM/21101539

Between 20 August and 6 September, a further five died leaving only 10 survivors (Messager de Tahiti, 12 September, 1863).

More tragedy followed when quarantine was breached and the epidemic spread to the wider Nukuhiva population claiming 960 lives. A further 600 died on Ua Pou, when a canoe carried the virus ashore.

In October, 1863 with the smallpox epidemic raging, and no ship willing to take them further, Davida Numangatini wrote urgently to the Imperial Commissary of the Tahitian Islands. “A captain brought us thus far,” he wrote, “and put us ashore at Nukuhiva, because there was a sickness amongst his crew and amongst the Mangaians. One of these was sick, but he is now cured. We are four of us from Mangaia, one from Atiu, one from Tahiti, and one from the Penrhyn Islands – seven in all. Have pity on us, so that we maybe enabled to get to Tahiti ... Have pity upon us … from Davida, at Nukuhiva.”

The Messager de Tahiti reported that ‘Davida and his companions have only a few days to wait, and have no reason to be personally afraid of a disease, which has respected them at the time when they had most reason to dread it’ (Messager de Tahiti 10 October, 1863).

It was not until April, 1865, eighteenth months later, that Davida and his companions finally reached home. “You may imagine the aged king’s joy at once more beholding the face of his son”, wrote the Rev. Wyatt Gill.

Local history records that Davida and his companions were accompanied from Peru by Mana Samuela Ariki of Mauke. Akaiti Ponga kavana has recorded that – “He (Samuela) met Davida, a son of Numangatini, while in slavery. In an effort to gain control over Mangaia the French complied with a request from the Mangaians to return Davida to them. The French also returned Mana Samuela Ariki to the Cook Islands. When the French ship returned to Mangaia ...with Mana Samuela Ariki and Davida on board they saw the English flag hoisted ashore. Realising they could not succeed in gaining Mangaia as a French territory, they threw Davida and Mana Samuela Ariki overboard. They swam ashore.”

Florence Syme-Buchanan has reported a Maukean story that a close friendship also developed in Peru between Davida and another Maukean called Teveta – “The Ziona church bell on Mauke is said to have been brought back from Peru by Davida… According to local historians, Davida befriended Teveta, a Maukean while in Peru and when slavery was abolished the men exchanged gifts before parting ways. Teveta gave Davida a gold ring – Davida’s gift was the bell. Teveta returned to Mauke and gave the bell to Ziona Church on completion of construction in 1882.”

Something else Davida and his companions brought back from their journeys was first-hand knowledge of how contagious and deadly the smallpox virus was. A little over one year after their return from Nukuhiva, Mangaia took its own measure to immunise its entire population against the virus.

“Through the kindness of a captain from New Zealand, we obtained a little vaccine lymph towards the close of last year,” wrote the missionary William Wyatt Gill in March 1867.

This “vaccine lymph” was fluid extracted from the blisterlike sores caused by cowpox. The “lymph” or infected fluid was injected into the upper arm of a patient and transferred between individuals through arm-to-arm transmission. The resulting cowpox infection provided immunity to smallpox.

“After successfully vaccinating our own children,” Gill writes, “with the help of two or three intelligent natives, I vaccinated nearly the whole population.” At the time the Mangaian population was 2237.

For the vaccine roll-out, “My plan was, after our early morning preaching service on Wednesdays, to vaccinate for about three hours without a moment’s cessation. This was kept up for about six Wednesdays in succession.”

There may have been some ‘vaccine hesitancy’ but Gill writes, “The more intelligent properly understood its utility.”

“Very many regarded it as a preventative of all foreign disease! Hence it was with great difficulty that several very aged men were induced to forgo so great a benefit. One quite feeble came there successive Wednesdays, leaning on his spear for support, to persuade me to change my resolution (against vaccinating the very elderly).”

The smallpox vaccine was first introduced to New Zealand in the 1850s, but vaccination rates declined as the century progressed, leaving NZ predominantly unprotected when the disease struck the country in 1913. Mangaia’s adoption of the vaccine in 1866, resulted in almost 100 per cent immunisation thanks to the knowledge of the virus gained by Davida Numangatini in Nukuhiva and Peru and the efforts of a pioneering missionary.

References

Harold E Maude, Slavers in Paradise 1862-64. Stanford University Press, 1981.

Frederick Moss, Through Atolls & Islands in the Great South Seas. London, 1889.