Makatea – hard work, harsh conditions, happy times

Saturday 23 October 2021 | Written by Supplied | Published in Features

Phosphate mining has left the French Polynesian island of Makatea with over one million holes. Cook Islanders were recruited to work at the mine on Makatea. Photo by Eric Guth (HAKAI MAGAZINE)/21102226

Hundreds of Cook Islands men flocked to Makatea – an island 220km northeast of Tahiti – during a New Zealand government-initiated labour scheme between 1942 and 1956. Roughly half the size of Mangaia in Cook Islands, Makatea was one of three raised coral atolls in the Pacific which was mined for its phosphate in the 20th century. The island was also known in the past as Mangaia-te-vai-tamāe. A new book entitled ‘Makatea’ attempts to capture a bit of the history around the phosphate industry and the Cook Islanders who worked on Makatea in the last century.

The book’s writer, Moana Moeka’a remembers first hearing about Makatea in the 1970s from his father who was from Ma’uke – an island 260km northeast of Rarotonga. Ma’uke is the closest island in the Cook group to Tahiti and Makatea.

“My father had a few older cousins who went to Makatea,” says Moeka’a. “But I remember him specifically telling me about one of them, Metua Rā’ea, who died at Maupiha’a – an island halfway between Ma’uke and Makatea. He wasn’t too sure as to how Metua died. But he told me that after his death, Metua’s mother took on an ‘ingoa mate’ (death name) – Moupia.”

Maupiha’a was where the three-masted German raider SMS Seeadler –commanded by (Count) Felix von Luckner – was wrecked in August 1917. The Count and some of his men ended up sailing and landing at ‘Ātiu and ‘Aitutaki, before being captured in Fiji and interned in Auckland, New Zealand until the end of the war.

In 2007, a former worker Paku Teokotai/Nganu told Moeka’a that a couple of nights after leaving Rarotonga in June 1947, the vessel L’Oiseau des Îles struck the reef at Maupiha’a. Only men from Rarotonga were on board the boat.

Nganu said the workers had to unload all the cargo and their possessions onto the reef, and help pump/bail sea water out of the boat. He said that a Ma’ukean man named Metua died, after working in water in the hull. Nganu remembers the workers being picked up at Maupiha’a by a British boat a few days later and taken to Makatea.

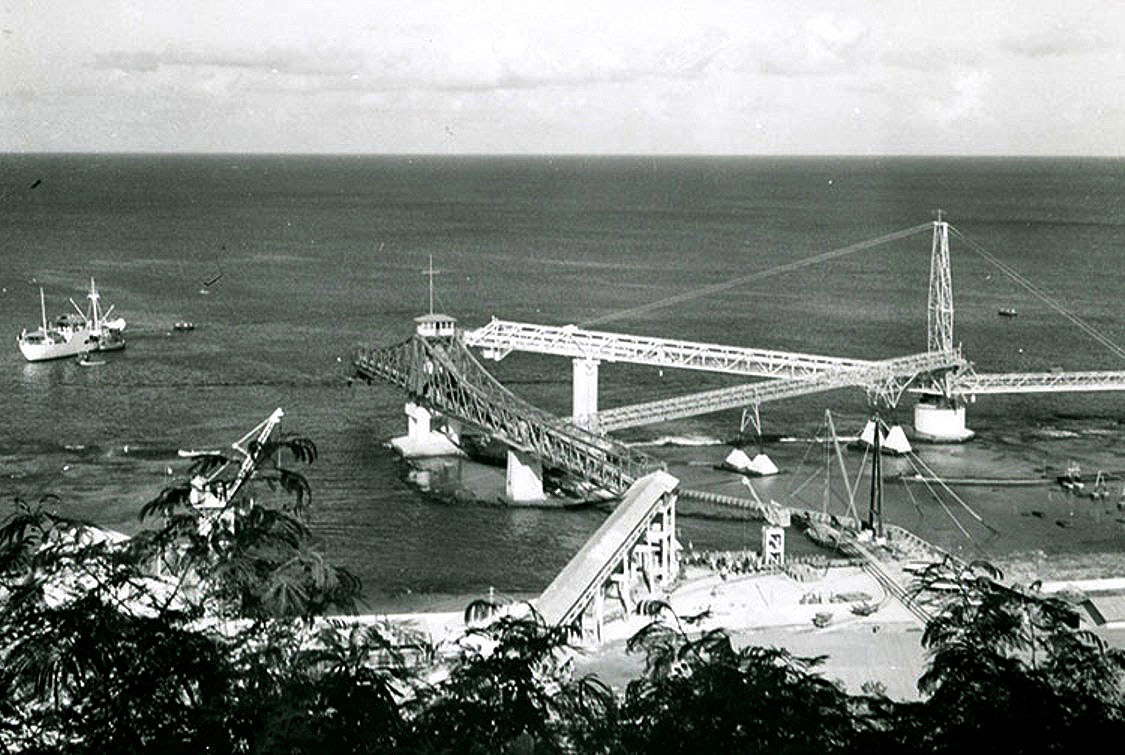

In the early days of mining, small locomotives moved phosphate from the extraction zone to the port, but were abandoned once a new conveyor belt system was implemented. Photos by Tahiti Heritage (historical) and Eric Guth (modern)/21102228/21102227

The first ‘contingent’ of men from Cook Islands under the work scheme left Rarotonga on 28 December 1942. The last lot of indentured Mangaian workers departed Makatea in February 1956.

Compagnie Francasise des Phosphates de l’Oceanie (CFPO) – the company which mined Makatea – would pick up the Cook Islanders on phosphate cargo boats from New Zealand, or on its own schooner, L’Oiseau des Îles.

The men were contracted for 12 months, and most worked as diggers. In 1943 the monthly wage was four pounds.

The phosphate had to be dug out of the ground manually at sites all over Makatea. The diggers were taken by train to their place of work before 6am each morning, Monday to Friday.

Diggers were required to dig three tons each day and they received a bonus for exceeding this daily total. The ‘repo’ was shovelled into wheelbarrows which –when full – were rushed along a maze of planks up to wooden platforms and emptied into the tubs/wagons below, which were then towed away by train to the ‘factories’ near the port at Temao.

But the workers in the scheme were not the first Cook Islands indentured labourers to be engaged in Makatea.

There were 48 Manihikians/Rakahangans employed in Makatea in 1914 –

just after a hurricane devasted their island atolls in January.

And group of 40 ‘Aitutakians (including women and children) went to Makatea in mid-1917.

Workers loaded phosphate onto ships at Temao, Makatea’s only port, until 1966. Louis Molet/Tahiti Heritage/21102229

The ‘Aitutakian labourers encountered problems and detailed their complaints in a letter dated 17 December 1917 to the Cook Islands resident commissioner Frederick Platts.

“Do you think that one roll of cooked bread – flour with meat is sufficient for one man for his dinner and sometimes a few slices of kumara to go with his salmon for one day?” asked Teora who was a foreman.

Teora said workers were being chased away from the hospital when going to see the doctor, and their money docked if workers were unable to work.

Platts replied to Teora that it was unreasonable to rely on the Makatea company to provide for their wives and children. But he said that he had asked the company to take proper care of the sick.

With CFPO importing Japanese, Chinese and Annamite labour just after the war, the ‘Aitutakians were the last lot of labourers to be employed en masse from Cook Islands until the start of the work scheme in December 1942.

In February 1945, the Cook Islanders went on strike for one day over the supposed reduction in the sugar ration – just before the second Rarotongan ‘contingent’ was preparing to leave Makatea.

By then, word was getting out about the living standards and harsh working conditions faced by the indentured workers on Makatea.

The conditions in the camp were apparently sub-standard with allegations of over-crowded barracks, leaking roofs, inadequate toilet facilities and bad food.

A meeting in April 1945 on Rarotonga – which was attended to by some returning workers – discussed the situation on Makatea and called on the resident commissioner Bill Tailby to investigate the allegations.

The apparent lack of interest shown by the administration prompted those connected with the Cook Islands Progressive Association to reach out to Albert Henry in Auckland to see if he could do anything. A petition calling for the removal of Tailby as commissioner was also circulated in the community.

Henry, who was to become Cook Islands’ first premier, contacted Pat Potter from the Auckland Trades Council who wrote an article which appeared in the monthly Challenge publication in August 1945. The article by Potter was titled ‘Have New Zealand subjects been sold into slavery?’

The article accused the French company of blackbirding the Cook Islanders and getting them to work in appalling conditions.

“Charges proved to the hilt included rotten accommodation in filthy, crowded barrracks; lack of water; foul camp and cookhouse conditions; crudest of sanitary arrangements; bad, monotonous and unhealthy food consisting almost entirely of poor bread and tea; lack of medical arrangements, facilities for recreation or any amenities.”

Frank Bateson, the manager of AB Donald which was the recruitment agent for CFPO, believed that the complaints had some justification but because of his position, he had to keep his opinion to himself.

“The firm was accused of selling men into slavery,” he recalled in his book, ‘Paradise Beckons’.

Bateson, who arrived on Rarotonga in late March 1945, said that the four shillings per day was “certainly low” but “more than a man could earn in his home island, so there was never a lack of eager volunteers”.

Eventually a New Zealand labour inspector was sent to Makatea in January 1946 to check on conditions on the island. CFPO halted recruitment at the time until all the issues were sorted out with the Cook Islanders.

Recruitment resumed in June 1946 – without the ‘Ātiuans who were banned from going to Makatea after the return of workers in December 1945.

The ‘Ātiuans, according to CFPO, were the source of many problems at Makatea at the time – brought on by alcohol – and it was decided that no more groups from ‘Ātiu would be allowed back.

Despite being good workers, the CFPO recruiter Aiden Gooding told Tailby that “whenever there is trouble, the ‘Ātiuans are usually found to be at the bottom of it”.

The ‘Ātiuans were eventually allowed back to Makatea in January 1949 – thanks to the pleas of Vainerere Tangatapoto, the local Boys’ Brigade captain. Tangatapoto was to go on to represent ‘Ātiu as a member of the legislative assembly in 1958 (before self-government in 1965) and a MLA in 1968.

Makatea was to be a life-changing experience for many of the men. Some men married ‘Tahitian’ women and settled in French Polynesia, while a number of men – including six from Ma’uke – brought wives back from Makatea to start new lives in the homeland.

Repeta Ta’ū’ū continues to live in Ma’uke after marrying Te’ari’i Ta’ū’ū and emigrating there in the 1950s.

Ke’u Iro, who was born in Rarotonga of Cook Islands and Tahitian parents, still lives at Vai’ma’anga on Rarotonga. She spent some time as a child on Makatea when her father Tepou Rongotini Kelly worked there. She married Ioane ‘Vane’ Iro at Makatea and they both returned to Rarotonga in 1955. Her husband passed away in 2012.

Some men who went to Makatea never saw their homeland again.

Aaron Aaron, Oa Oa’ariki and Tuakana Ma’ao were all killed in work accidents. Teahui Ta’ū’ū – the brother of Te’ari’i – died in Rarotonga while on his way back to Ma’uke in 1947. Tangianau Aitau, a kavana on Mangaia, died just weeks into the first trip of a Mangaian group to Makatea in 1947.

Mining ceased on Makatea in 1966. But there are plans to mine the island again.

According to its website, SAS Avenir Makatea wants to set up a human-sized industry to recover the secondary phosphate layer by digging deeper into the former operating area, then fill the holes and replant vegetation adapted to the atoll ecosystem.

The French Polynesian government is expected to grant a 50-year mining concession to the company at the end of 2021.

Up until 2009, Moeka’a spoke to 10 former workers – some for less than half-an-hour – and, unfortunately, left things at that. The men interviewed were only a fraction of the hundreds of Cook Islanders who worked in Makatea between 1942 and 1956.

“But what the men had to say was invaluable. Considering that I interviewed the men about 60 years after they had been to Makatea, all were quite clear about most of the things they got up to while on the island. Their memories relating to dates might have been sketchy. But all spoke of hard work, happy times, good money – compared to home – and a desire to return to Makatea after completing their first one-year contract.”

However his biggest regret about writing about Makatea was not knowing then what he knows now.

“It’s like most things historical. You don’t really know until years later.

“There were a few men in my home village of Ruatonga, who were still alive in the 1970s, who travelled to Makatea. I only found out after I had read a few of the workers’ lists in 2020. A few men that I knew in Auckland when I lived there in the 1980s and early 1990s, also went to Makatea.”

Moeka’a says the book is not a complete history on Cook Islands’ involvement in Makatea.

“But I’d like to think that at least there is a book that touches on this important part of our history.

“It just goes to show that we as Cook Islanders are fast losing our history and if we don’t do anything about it, well, it becomes history and we forget all about it.”

The book will be launched on Thursday, October 28 at the National Museum at the Ministry of Cultural Development, Tauranga Vananga.

‘Makatea’ is the third book written by the author, following ‘The Last Army Recruits’ (2016) and ‘Rangitukua’ (2019).

Matakino Tomokino. After working in Makatea for two years, he married an 'Ātiuan woman and has lived on 'Ātiu for almost 65 years. Photo Tekura Moeka’a. 21102221

Ke’u Iro – a resident of Vaima’anga, Rarotonga. She married her husband Ioane Iro in Makatea. 21102220

Repeta, the wife of Te'ari'i Ta’ū’ū, was still living on Ma’uke in June 2021. She was staying on Makatea in the 1950s when she met her husband. 21102222

Sepha Mose Marsters was the feeding brother of Aaron Aaron who was killed in an accident at Makatea in March 1948. Although Makatea records state that Marsters was born on 15 May 1929, his family are adamant that he was born on Palmerston two years previously. Marsters was the focus of a Tane Toa Kuki Airani evening on Rarotonga in May 2021. He went to Makatea in the Rarotonga group in 1947 and 1948, and lives in Titikaveka. Photo courtesy of Sharon Marsters/21102223

Ta’aki Ruatoe in front of Maruatanui o Numangātini, Oneroa, Mangaia on Ariki Day -- Friday 2 July 2021. Ruatoe went to Makatea in the 1950s and like fellow Mangaian Ora Rere, returned with the last group in 1956. He married his wife, Taku, in 1962 and has lived on Mangaia ever since. He worked with the railcars which carried the phosphate in Makatea. Ruatoe was born on 25 May 1935 and he is the kavana (tribal head) of the puna of Tavaenga. Photo Numangātini Ariki IX Tangi Tere’api’i/21102225

Ora Rere worked as a digger and travelled to Makatea on at least four occasions. He was in the last Mangaian group to return in February 1956. He celebrated his 88th birthday on Mangaia on 13 June 2021. However his birth date on his recruitment record states that he was born in 1930. As the recruitment age was 18, it was not surprising for teenage males keen to go to Makatea, to overstate their age. Photo courtesy of Leanne Taokia/21102224