Spain and Russia in Cook Islands

Saturday 23 July 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

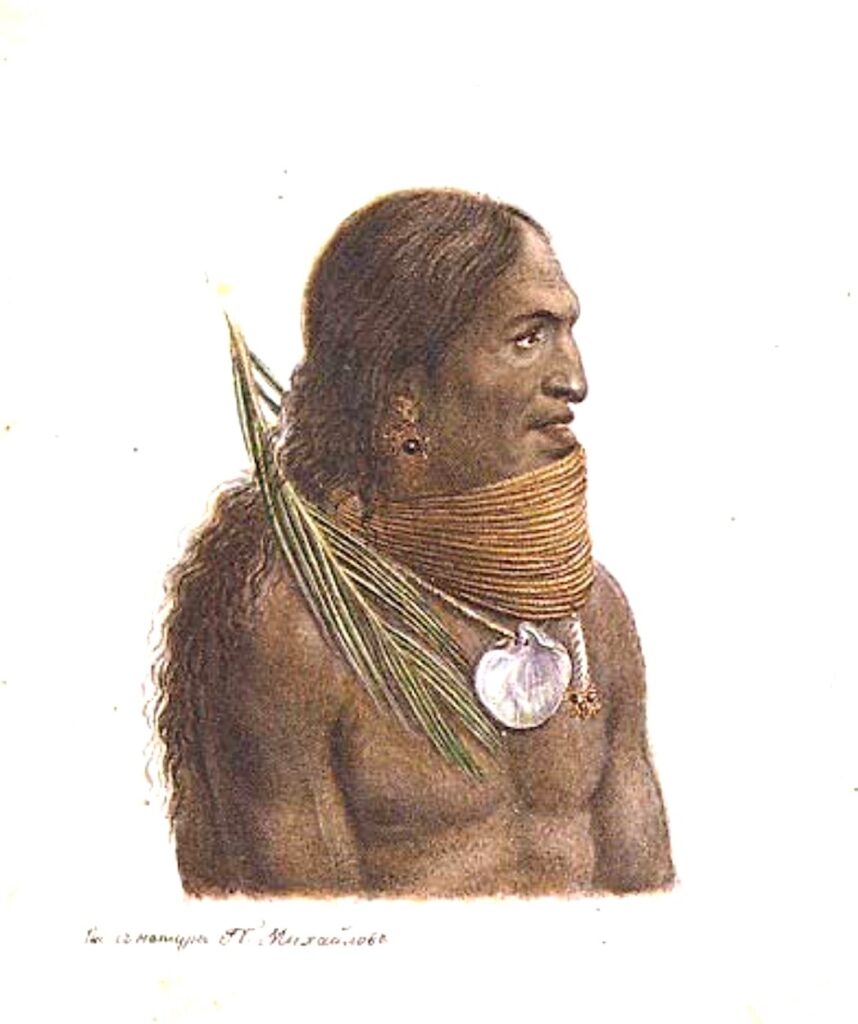

Figure 1 – A young Rakahangan man wearing a headdress topped with folded hara (pandanus) and a neckband of woven hara both stained reddish-brown with nenu (nono) dye (source; Russian State Museum). Photo: SUPPLIED/22072221

Four hundred years after it was settled by Polynesians, Rakahanga was visited by a Spanish Expedition searching for Terra Australis, then two centuries later by Russia’s First Antarctic Expedition.

In both cases the expeditioners left fascinating insights into Rakahagan life two and four centuries ago.

Rakahanga was permanently settled around A.D. 1200, according to oral tradition by a single family from Rarotonga

Four hundred years later, in 1606, the Portuguese-born Spanish explorer Pedro Fernandes de Quirós (1565–1614) visited the atoll. One of the chroniclers of this visit, Torquemada, records that de Quirós’ was so struck by the beauty of the islanders, that he named the atoll Gente Hermosa or the island of “beautiful people”.

Pedro Fernandes de Quirós was on a voyage in search of Terra Australis when, on the 2 March, 1606 his ships, Capitana and Almiranta, sighted “a small island, 3 to 4 leagues in circuit, covered with coconut palms, but no other trees”.

Two local canoes came off to the Spanish ships and they were described as “each holding three or four natives” and were followed by “a fleet of ten small canoes, rowing fast and as if racing, … We saw on board them some tall men, well made and handsome, and of a good colour”.

“They all came singing to the sound of their paddles, one of them leading, to whom the rest replied… Many stood upright, and with arms and hands, legs and feet, and with their paddles, they made sounds with great dexterity, dances, and gestures. Their chief theme was music, and to show themselves joyful and merry before our ships.” (de Quirós, 1894; 210).

From their ships the Spaniards could see “a village under a grove of palm trees, near a lake (lagoon) which the island has in the middle”. On closer inspection, the village, Te Kainga, was found to be made up of houses constructed of coconut “wood and leaves” each having “four vertientes, (slopes) curiously and cleanly worked, each with a roof, open behind.”

“In the houses” de Quirós noted “ a great quantity of soft and very fine mats and others larger and coarser; also tresses of very golden hair, and delicate and finely woven bands, some black, others red and grey; fine cords, strong and soft, which seemed of better flax than ours, and many mother-o’-pearl shells, one as large as an ordinary plate.” (de Quirós, 1894; 215-6).

“Of these (pearl) and other smaller shells,” he wrote, “they make … knives, saws, chisels, punches, gouges, gimlets, and fish-hooks. Needles to sew their clothes and sails are made of the bones of some animal, also the adzes with which they dress timber. They found many dried oysters strung together, and in some for eating there were small pearls.” (de Quirós, 1894; 215).

The people were well clothed – “from the more tender shoots (of the coconut) they weave fine cloths, with which the men cover their loins, and the women their whole bodies.” (de Quirós, 1894; 216).

They also wore “palm leaves made like tippets (capes) over their shoulders.”

On shore, de Queirós observed a number of large outrigger canoes, with sails made of coconut matting, capable of transporting 50 or more people. These canoes would have been used in the periodic tūmutu or migration between Rakahanga and Mahihiki (40km away) when a rahui was placed on the whole of Rakahanga.

“Some of these (are) very large vessels, twenty yards in length and two wide, more or less, in which they navigate for great distances… Their build is strange, there being two concave boats about a fathom apart, with many battens and cords firmly securing them together.” (de Quirós, 1894; 216).

Masts, rigging, sails, rudders, oars, paddles, utensils for baling, lances and clubs were all, according to de Quirós, made of materials obtained from the coconut tree.

At the time, the land was “divided among many owners, and is planted with certain roots, which must form their bread. All the rest is a large and thick palm grove, which is the chief sustenance of the natives.” (de Quirós, 1894; 216).

The “roots” would have been pūraka or atoll taro, cultivated in pits excavated into the atoll’s freshwater lenses. The archaeologist Justin Cramb, who has undertaken excavations on Rakahanga over recent years has reported “massive networks of swamp taro cultivation pits” with elevated spoil mounds. In 1874, the trader H. B. Sterndale reported “artificial trenches as much as a mile long and 100 yards wide. They are filled at the bottom with a mould of sand mud, and thickly planted with pūraka … When we come to consider that a work so remarkable was effected by … toiling with wooden implements, bursting up the rock with wedges and levers, and carrying it out of the excavation to a considerable height, along with thousands of tons of' gravel and sand, one cannot escape a feeling of intense admiration for their energy and perseverance.”

At the time of de Quirós’ visit, the estimated total population of Rakahanga was 1200 – of whom the visitors observed around five hundred, describing them as “the most beautiful white and elegant people that were met with during the voyage”.

de Quirós described one Rakahangan women as “ – a lady, graceful and sprightly, with neck, bosom, and waist well formed, hair very red, long and loose. She was extremely beautiful and pleasant to look upon, in colour very white…” The chronicler Torquemada, described the island’s women as “very white” and “if properly dressed, would have advantages over our Spanish women”. He describes them “clothed from the waist down with reeds or white fringes of well woven palms…”

de Quirós paid particular attention to two men – one was an older man who seemed to be a warrior – and the second, a “king or chief”.

The warrior, “wore a helmet of palm on his head, and a sort of shirt, also of palm leaves but all painted red”. The warrior was performing perhaps the Rakahangan version of a wero or taki. He is described as making “fierce faces with his eyes and mouth. In a very loud voice he seemed to order us to surrender. With his lance, brandishing it menacingly, he made as many thrusts as he could. With the intention of making him quiet, two muskets were fired off. The others cried out and threw up their arms, but he made light of it.” (de Quirós, 1894; 211).

Brief mention is made of the ariki - “the king or chief (carried) in a litter (pa’ata) on their shoulders, holding palm leaves to shade him (de Quirós, 1894; 213). This account predates the establishment of a dual arikiship on Rakahanga around 1650 (Cramb and Thompson, 2022).

Close attention was given to some of the island’s youth. de Queirós writes admiringly of a young Rakahangan seen bailing one the canoes that came off to his ship – “His red hair came down to the waist. He was white as regards to colour, beautifully shaped, the face aquiline and handsome, rather freckled and rosy, the eyes black and gracious, the forehead and eyebrows good, the nose, mouth, and lips well proportioned, with the teeth well-ordered and white. In fine, he was sweet in his laughter and smiles, and his whole appearance was cheerful. Being rich in so many parts and graces, he would be judged to be very beautiful for a girl; but he was actually a youth of about thirteen years. This was he who at first sight stole away the hearts of all on board the ship; he was most looked at and called to, and he to whom all offered their gifts, and to whom the Captain, with great persuasion, desired to present a dress (clothes) of silk, which he accepted, and put on with much grace. It was pain to the Captain that the youth could not be kept, to take as a proof of the greatness of God in those parts.”

The historian Serge Tcherkézoff has noted how the Spanish explorers were keenly aware of skin colour, admiring the Polynesians for colouring within the European range, in particular their proximity to the Spaniards own skin colour. de Queirós’ also equated “barbarity” with ugliness and beauty with the angels. “Never in my life (have I) felt such anguish,” he wrote of a Marquesan youth, “as when I thought that so beautiful a creature should be left to go to perdition”.

The following day de Queirós’ ordered his second in command, Luis Vaez de Torres, to proceed on shore with an armed party “to get the wood and water of which we are in want” but with the added instruction “to bring on board at least four boys, one of them being the youth who has already been described, and the others to be like him.”

The landing was opposed and the subsequent fighting resulted in the death of thirty Rakahangans, causing Torres to rename Rakahanga, “Matanzas” (the Island of Killings).

The slaughter is difficult to reconcile with the Spaniards seeming recognition of a common humanity with the Rakahangans, on the basis of their “whiteness” and “beauty”.

The incongruity recurs when shortly after the killings, Torres encounters another youth described as “so beautiful and with such golden hair, that to see him was the same as to see a painted angel. With crossed hands he offered them his person, either as a prisoner or to do what they liked with him. The Admiral (Torres), seeing him so humble and so handsome, embraced him and dressed him in breeches and shirt of silk … The boy, to show his pleasure, climbed up some very tall palm trees with agility, and threw down cocoa-nuts for us, asking if we wanted more.” (de Quirós, 1894; 213).

Accounts by members of the Spanish expedition also mention the presence of dogs “of a small breed” and “dogs like those of Castille” on Rakahanga at that time. Justin Cramb has recently excavated dog remains on Rakahanga and suggests they accompanied the first settlers but became extirpated some time between 1606 and 1820.

While the Spaniards left no visual representation of the Rakahangan people, the next scientific expedition did. This was a Russian expedition led by Bellingshausen which visited Rakahanga on 7 August 1820, renaming it “Grand Duke Aleksandr Nikolaevich's Island”.

The Russian vessels Vostok and Mirnyi, stood off the atoll for two days, while efforts at gift exchange were interspersed with sporadic outbursts of violence.

Russian records of the visit mention canoes “with pointed bows and regularly carved pearl-shell ornamentation, (that) carried six, eight, or ten well-muscled islanders apiece. They were equipped with single outriggers but lacked sails and masts.”

The encounter was recorded visually by the Vostok’s artist, Pavel Nikolaevich Mikhailov (1786-1840). His drawings, now in the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, include water colours based of heads of two Rakahangan men, with the inscription, “Natives of Grand Duke Aleksandr Nikolaevich Island”; and an image of a Rakahanga canoe and shoreline.

One image (Fig.1) shows a young Rakahangan man wearing a head dress with a woven band topped with folded hara or pandanus. This has been stained reddish brown with dye derived from the nenu (Morinda citrifolia). He is additionally wearing a neckband made of woven hara, also stained with nenu dye and a tippet or cloak made of woven coconut leaves is suggested.

The second image (Fig. 2) shows an older man, wearing a neck ornament that may have been used to protect the throat or pulled up as a visor or helmet in fighting. It was described by Bellingshausen as “a visor ... woven from coconut-fibres, in the form of little hoops like riding-whips, each one-sixth of an inch in diameter, to the number of twenty-one; one-third of these being tied up behind, with thin cords, in four places” (Barratt, 1998; 209). Details “of ornamental scarring and tatau on the upper arm” are faint but visible. This picture also shows ear and breast ornaments made of “skilfully worked nacred shells”; as well as an earring and pearl-shell chest ornament, the earring topped with a single pearl and the breast shell ornamented with a drop of several pearls.

In 1849, the Christian missionaries Aporo and Tairi arrived at Rakahanga and later, despite concerns among Rakahangans “at the prospect of famine resulting from permanently populating both atolls” the dangerous travel associated with the tūmutu ceased. The Rakahangan population of 1200 was divided into three settlements – two on Manihiki and one on Rakahanga.

The village of Te Kainga was abandoned and a new, more spacious, settlement established to the south. It was called Matara, signifying the break from the old ways.

References

Barratt, Glynn, 1998, “Russian Activity among the Cook Islands, to 1820”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal; 34-98

Cramb, Justin and Victor Thompson, 2022, “Dynamic Sustainability, Resource Management and Collective Action on Two Atolls in the Remote Pacific”, Sustainability, 154; 5174

de Queirós, Ferdinand, 1894 The Voyages Of Pedro Fernandez De Quiros,1595 To 1606. Translated By Sir Clement Markham, Hakluyt Society London