Black-shouldered Lapwings: Rare vagrants on Rarotonga

Saturday 7 October 2023 | Written by Supplied | Published in Features, In Depth

The 2023 Maureen Goodwin lapwings in Muri. Photo Bob Goodwin/23100621

On the 30th of August, Maureen Goodwin saw two unusual birds on her inland Muri lawn. She googled and identified them as Australian Southern Lapwings rather than the Northern due to the black ‘ei kakī (collar). Over the next few days, they fed, ran over the lawn, and flew around the area, writes Gerald McCormack, director of Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust.

Unexpectedly, one died after eight days and the other after 10, apparently of natural causes. This was only the third time lapwings have been reported on Rarotonga in 30 years.

They are in the same bird family as the well-known Tōrea (Pacific Golden Plover), which breeds in Alaska and migrates yearly to spend the southern summer here and elsewhere in the South Pacific. Birds that visit yearly are known as migrants, while birds that arrive at erratic intervals are known as vagrants.

On Rarotonga, the first record of the Black-shouldered Lapwing was by the author on the grass at the western end of the Airport in 1993 on the 7th and 28th of October. It was nine years to the next record.

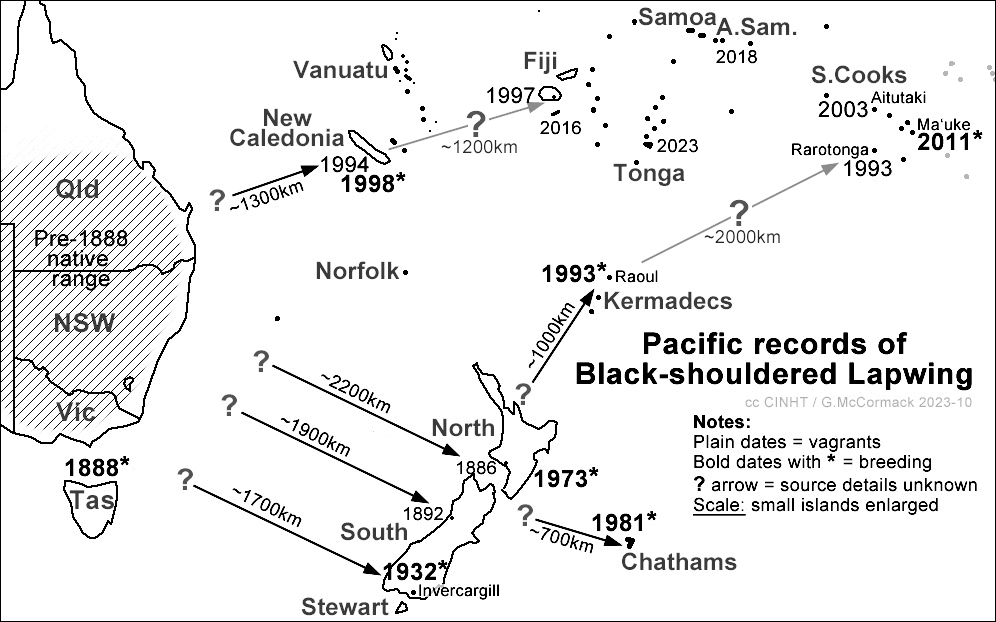

Map of known records of Black-shouldered Lapwings. Arrows starting with a question mark show the general location of origin. The Fiji and Rarotonga origins are speculative. 23100623

In 2002, on the 19th of October, Eddie Saul reported a similar lapwing on the field near Nikao Video, and Geoff Stoddart saw two birds in the same area on the 25th, of which he photographed one. On the 29th, the author saw one on the grass at the eastern end of the Airport.

There was a twenty-year gap to August 2023, when the Goodwin lapwings were reported. By any definition, the lapwing is a very rare vagrant on Rarotonga.

On Aitutaki, the first Black-shouldered Lapwing was reported with a photograph (eBird) in 2003 at the airport on the 28th of August by Eric VanderWerf, and presumably, the same bird was reported near the terminal on 12th October by Gary Turtle and Ruth Vomund.

Ma‘uke is a special case because it has a resident pair of Black-shouldered Lapwings. The two birds were first reported in 2011 on the 25th of August when Keiti Tuakana photographed them at the harbour. Basilio Kaokao monitored the birds and two years later reported a fledgling on the 28th of June 2013. In September this year, he reported that the young bird was still alive, and the three live mainly on the grass around the inland Water Protection Zone (No‘o‘anga Atua) and regularly visit the airport area.

The Ma‘uke lapwings in 2011 photographed by Keiti Tuakana. They raised a young in 2013. Parents and offspring were still alive in late 2023. 23100622

Native range expansion

In the 1800s, the Black-shouldered Lapwing was native to the Australian mainland from central Queensland south to Victoria and eastern South Australia. It is widely considered a subspecies (Vanellus miles novaehollandiae), with its plain-necked sibling, the Northern Masked Lapwing (Vanellus miles miles), native to Northern Queensland, Northern Territory and New Guinea.

In a contrary opinion, Birdlife International treats the two forms as separate species. However, regardless of whether it is a subspecies or a species, we focus on the form with the black collar and use BirdLife’s descriptive name, the Black-shouldered Lapwing.

In 1888, the Black-shouldered Lapwing spread south of mainland Australia to establish itself in Tasmania.

In New Zealand, more than 1700km from Australia, the first lapwings were recorded in 1886 near Wanganui and 1892 near Hokitika. There were no more reports for thirty years!

In 1932, a pair bred at Invercargill Airport; by 1950, there were over a hundred in the immediate area. By 1970, they were very common up to 100km from the airport, with isolated groups throughout the island. In 1973, they were reported in the southern part of the North Island, and by 1990, they were everywhere, including the Far North.

In 1981, they flew 700km east from one of the main islands to breed on the Chathams. And by 1993, they had flown 1000km north of North Island to breed on Raoul Island in the Kermadecs.

In New Zealand, they are known as Spur-winged Plovers, and although they are recent settlers, they are classified as native birds because they introduced themselves without human assistance. They are protected along with all Aotearoa native birds, although many consider them invasive.

The rapid spread of the Spur-winged Plover in New Zealand is particularly interesting regarding the genetic viability of small founding populations.

When 30 Kākerōri (Rarotonga Flycatcher) were moved from Rarotonga to Ātiu in 2001-2003, and 27 Kura (Rimatara Lorikeet) were moved from Rimatara to Ātiu in 2007, there were concerns that such small founding numbers would lack the genetic variability to enable them to flourish in the future.

The spread of the lapwing throughout New Zealand from a founding pair seems to mock such concerns, despite the expectation that a few more genetic packages probably arrived from Australia during the expansion.

Lapwings are strictly land-birds and cannot land or feed in the ocean. General information indicates they can sustain a flight speed of about 65km/h. eBird/23100612

Pacific islands exploration

New Caledonia is about 1300km east of Australia, and the first Black-shouldered Lapwings were reported in 1994, and they were breeding there by 1998.

Fiji is about 1200km east of New Caledonia, and the first lapwings were reported on Viti Levu near Suva in February 1997 and July 1999 – one Black-shouldered and one unknown. While it is reasonable to think these birds came from New Caledonia or Australia, we cannot rule out the North Island or the Kermadecs.

The Rarotonga 1993 Black-shouldered Lapwing arrived before any were recorded in New Caledonia or Fiji, which makes its origin in the Kermadecs or North Island reasonably likely. This source for the Cook Islands is further reinforced by the Aitutaki 2003 and Ma’uke 2011 birds, which arrived before any had been reported in Tonga or the “Samoas”. However, the few reported sightings could be misleading because, without a doubt, most lapwings landing on tropical islands would not have been reported, so we will never know their early distribution in our region.

In more recent years, reporting has increased. Although no breeding reports exist in Fiji, it has had new sightings of vagrants. In March 2018, there were four Black-shouldered Lapwings near Suva (eBird), and on Kadavu Island, two indeterminate birds were recorded in April 2016 (eBird) and a Black-shouldered in March 2023 (iNat).

Single birds were reported in American Samoa in December 2018 (eBird) and in Tonga in February 2023 (iNat). Both were Black-shouldered.

Trans-oceanic flights

Lapwings are strictly land-birds and cannot land or feed in the ocean. General information indicates they can sustain a flight speed of about 65km/h. This means that the 1700km trans-oceanic flight from Australia to New Zealand would have taken about 26 hours, with a tailwind, much less.

For our Cook Islands vagrant lapwings, the 3000km flight from North Island would have taken about 46 hours or two days, and we know our migratory Karavia (Long-tailed Cuckoo) does this non-stop flight every year. On the other hand, if our lapwings came non-stop 4500km from Australia, it would take them about 70 hours or three days. Even this is not unreasonable because their relative, the Tōrea (Pacific Golden Plover), does a five-to-seven-day non-stop flight from Alaska to islands around Rarotonga each year. The main difference in both cases is that the migrant adult birds know where they are going, while vagrant lapwings are just cruising over the ocean on the off-chance of finding land.

I wonder where the two Goodwin lapwings started their trans-oceanic flights?