Wheel of Fortune?: The‘revolutionary’ invention that was born on Rarotonga

Saturday 9 September 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Art, Features, Memory Lane

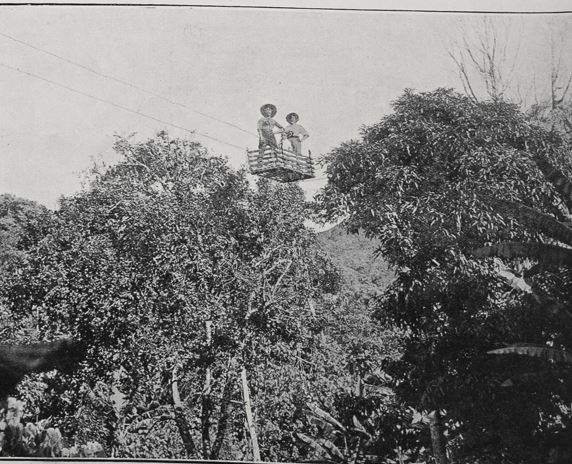

Henri Rey’s “new aerial tramway at Rarotonga which has opened up a large fruit-growing area to the coast.” Auckland Weekly News 6 July 1911 (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection)

For two decades Rarotonga was home to the inventor Henri Rey who partnered with local resident William McBirney to form the Rey Wheel Company of Detroit, Michigan. Story by Rod Dixon and Allan Tuara.

Many Cook Islanders will be familiar with the family name McBirney. Its progenitor in the Cook Islands was William McBirney (1871 – 1956), an Anglo-Irishman, former British Army warrant officer and member of the Royal Garrison at the Tower of London. He arrived in Rarotonga with his family in December 1908 and died in 1956 at the age of 85. William is recorded on his gravestone near the Panama cemetery as a “Soldier, Adventurer, Botanist, Writer and Poet.” He was also a contrarian, an anti-colonialist, and a businessman. And in this latter capacity, he enters this story of a revolutionary car wheel.

The star of the story is the Rarotonga-based Henri Rey (1885 – 1971), the son of a French father and a French Tahitian mother, trained in Pape’ete as a charron-forgeron orblacksmith and cartwright. In October 1907 Henri, aged 22, left Pape’ete on the cargo ship S.S. Hauroto which stopped off at Aitutaki and Rarotonga en route to Auckland. A year later, in October 1908, Henri returned to Rarotonga to set up a number of businesses.

“I needed land,” Henri recalled in 1965, “enough for a shop and growing a cash crop. I decided on growing the mountain banana, which I would sun dry into a sort of confection that was much liked in both the Cook and Society Islands. After asking around, I learned that only Queen Makea could sell or lease land... Queen Makea was very polite to me and seemed interested. She agreed to lease me 28 hectares of the land I wanted for £5 a year.”

“I set up shop and planted 14,000 banana plants of a Samoan variety called Cream Banana; also, Valencia oranges, Emperor mandarins, and Lisbon lemons” (Davenport, 2004).

When his crops matured, Henri built a zip wire to transport the fruit in cases from his inland plantation to the sea-shore, the first and only “aerial tramway” in Rarotonga.

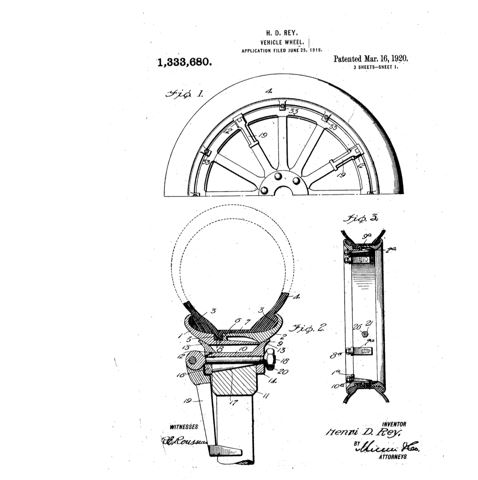

A drawing from the Rey Wheel patent document – U.S. Patent Office, 1920.

On a return visit to Pape’ete in 1913, Henri “ran into a man with a motion picture machine and some films... His plan was to take it back to Avarua and build a hall to show the pictures. So he and a partner [Willie Parau Browne] purchased lumber for £1000 and put up a large building they named Royal Hall, in honor of the Queen.”

“We charged 2 shillings and 6 pence which was high, but the hall was packed every night, and we soon made our expenses back and a lot more. That was in 1913. We took the film to other islands and arranged to get fresh films from New Zealand.”

The Royal Hall cinema at Taputapuatea, built by Henri Rey and Willie Parau Browne in 1913. The original building was “blasted into a heap of tangled wreckage” in the hurricane on 10 March, 1943. It was replaced in 1944 as the Victory Theatre.

“One thing I was always being asked about was the kare ore’enua, the buggy without horses… so I decided to buy one.” He travelled to Wellington, April 1912 and January 1913, and purchased two Stuart cars produced by the Star Motor Company of Wolverhampton, England. These arrived in Rarotonga in October 1913 on the Union Steamship Talune. Henri and his brother Jules “started giving rides through [Avarua] town for two shillings a person, five at a time. My brother Jules and I made trip after trip, every day. My word, the money we were making!” The Otago Daily Times, (19 December 1913) calculated the brothers had earned £1000 in their first month on Aitutaki alone.

(Back row, left) Jules Rey with Rarotongan joy-riders in one of the Rey’s two Stuart cars (1913). The Star company’s car-badge can be seen below the radiator cap.

Jules took one of the two cars to Tahiti and ran a taxi service there with similar success. That left Henri without a spare when his car broke a wheel in a Rarotonga pot-hole. “All of a sudden, an idea came: instead of fixing the broken wheel, I would make a new one, and the new one would be of a completely different kind and design.”

“I took the broken wheel and broke out all the spokes,” Henri explained to interviewer William Davenport in 1965. “Then I took the metal rim of the broken wheel and bored eight holes evenly spaced around the outer flange and eight around the inner flange… In each of these 16 holes I put a lug that stood out from the rim a little. Then I took all the spokes out, which left the hub in two parts, an outside and an inside. In a circular plate of common 3/8 inch iron I cut eight spoke-like projections and a second one exactly the same. The two plates were hammered into concave shapes so that when they were placed together, concave side to concave side, there were 16 projections.”

“When the two plates were fitted into the old rim there were 16 plate projections instead of spokes, and when tightened by a nut on the axle, the two concave plates were pressed into the old rim. This was not an old artillery-type wheel or a disc wheel; it was a Rey wheel.”

Henri’s close friend on Rarotonga, William McBirney, convinced him to apply for a US patent and offered to accompany Henri to Washington and pay all expenses as his initial investment in the business. They left Rarotonga on the R.M.S. Moana arriving in San Francisco on 10 June 1918.

In San Francisco, they found a workshop that was able to fabricate five prototypes of the Rey Wheel.

“Now we were ready to go east to get the patent.’ Henri told Davenport. “In Washington, D.C., we found a man named Trainer who was both an engineer and a lawyer, and he went to work. Somehow, he got the papers through [the Patent Office] quickly, and McBirney and I took the train back to San Francisco. We bought a rather late model of a Dodge Overland to mount the [Rey] wheels on and started out to drive across the county. We headed for Washington again and went straight to the War Office. We were welcomed there and several officals went over the wheel carefully. They were enthusiastic.

“Can you produce them?

“No, of course not, we are just from the South Seas.

“Then [the War Office official] explained that every shop and factory in the U.S. was working at full capacity [for the war effort]. There was no hope that the government would adopt it.”

Disappointed, they travelled back to San Francisco in their Dodge Overland and caught the R.M.S. Moana back to Rarotonga, patent in hand.

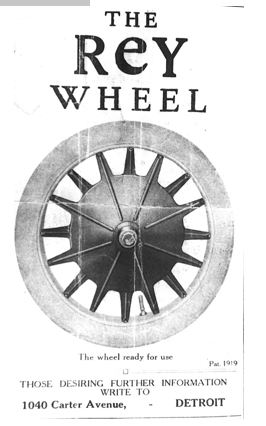

After the war, Henri and McBirney decided to return to the U.S. to establish the Rey wheel company and seek out car-makers interested in equipping their cars with Rey wheels. To raise enough cash for the new company, Henri sold off some of his businesses in Rarotonga and left the rest in the care of his brother Jules. He and McBirney set sail, this time for Detroit, Michigan, car capital of the U.S., on the R.M.S. Tahiti, arriving 20 June 1921.

In Detroit, they hired a local lawyer and incorporated a stock company, the Rey Wheel Company of Detroit, issuing $400,000 worth of stock with Henri holding half and McBirney as Company Director.

According to Davenport, “They fitted three more cars with Rey wheels, and first went to the Kelsey Wheel Company of Detroit who made artillery-type wheels for General Motors and Ford. They were interested, but not willing to abandon their huge investment in their plant and hundreds of hectares planted in hickory for spokes.” Spokes in the wheels of early motor cars were made from wood.

“Then I went to the Hayes Wire Wheel Compare, but they thought wire spokes were going to take over. Then I read the French were working with something called the balloon tyre. I suspected that this was not in our favor. I saw engineers at the Scripp-Boothe Division of General Motors, and they were interested and sent me on to the Experimental Division… [who] went over the wheel and decided to try it out on a Chevrolet and [were] favorably impressed.”

“I met with a man who was Chief Engineer with the Pierce-Arrow Company [Buffalo, New York], and he wanted to quit them and sell the Rey Wheel in Europe. However, he wanted 50 percent of the whole company. Our Director wanted me to accept, but I refused... For the first time there was some unpleasantness within the company. Everyone was restless.”

This ‘unpleasantness’ probably refers to a disagreement between McBirney and Henri over whether or not to take this deal. McBirney’s grandson Allan Tuara recalls a family story in which “Henri blamed the old man for wanting to sell to the best available bidder.”

They next met with “a man who was a Director of the Allegheny Company which made wheels for the Budd Company of Philadelphia.”

William McBirney ca. 1930

The Budd Company were impressed but were contracted to Michelin and their disc wheel and balloon tyre. They told Rey they would give him $200,000 – the value of the Rey Wheel Company’s remaining stock offer – to “put your wheel on the shelf. Take your $200,000 and go back to Tahiti.” I knew that was the end of the Rey Wheel Company.”

There is no record of whether Henri and McBirney took the money or if either ever profited from the venture.

Sometime later, Henri and Jules returned to Tahiti and established new businesses in Pape’ete. Undeterred by his experiences with the Rey Wheel, Henri continued with his inventions. In the period 1920 - 1954 he was granted a total of 29 U.S. patents for inventions such as a double clutch vehicle transmission, wheels with compression spokes fabricated by sheet metal, gearshift transmissions improvements, etc. When William Davenport interviewed him in 1965, Henri was 80 years old and running a part-time mango export business while practicing homeopathic medicine. He died in 1971 aged 86 years.

William McBirney returned to his home and plantation in Arorangi where he played an important role in the development of export markets for Cook Islands tomatoes and other crops and acted as a local adviser for scientists visiting the islands (as his grandchildren continue to do). He died in 1956 aged 85 years. His descendants include, among others, members of the McBirney, Olsen, Nicholls, Tuara and Evaroa families.

References

This article is deeply indebted to William Davenport’s interview with Henri Rey in "Henri Rey" Expedition Magazine 46.3 (2004): n. pag. Penn Museum, 2004 Web. 08 Aug 2023