‘Ueata – catching shadows: Early photography in the Cook Islands

Saturday 5 August 2023 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Art, Features

Henry Winkelmann and colleagues on location, “Cook Islands, 1903” (Photo - PH-ALB-264-p54-1, Gudgeon Album, Auckland Museum and War Memorial)/23080345

Photography came relatively early to the Cook Islands thanks to some missionary amateurs. The Mangaians had a word for it – ‘ueata, “capturing shadows”, writes Rod Dixon.

The first camera as we know it, was invented in 1839 when the French printmaker Louis Daguerre demonstrated the process of capturing and retaining permanent images by combining light and chemistry on a durable surface. This was known as a “daguerreotype” and subsequently a “photograph”. However, making duplicate prints of a daguerreotype required specialised equipment and was a complicated and expensive process.

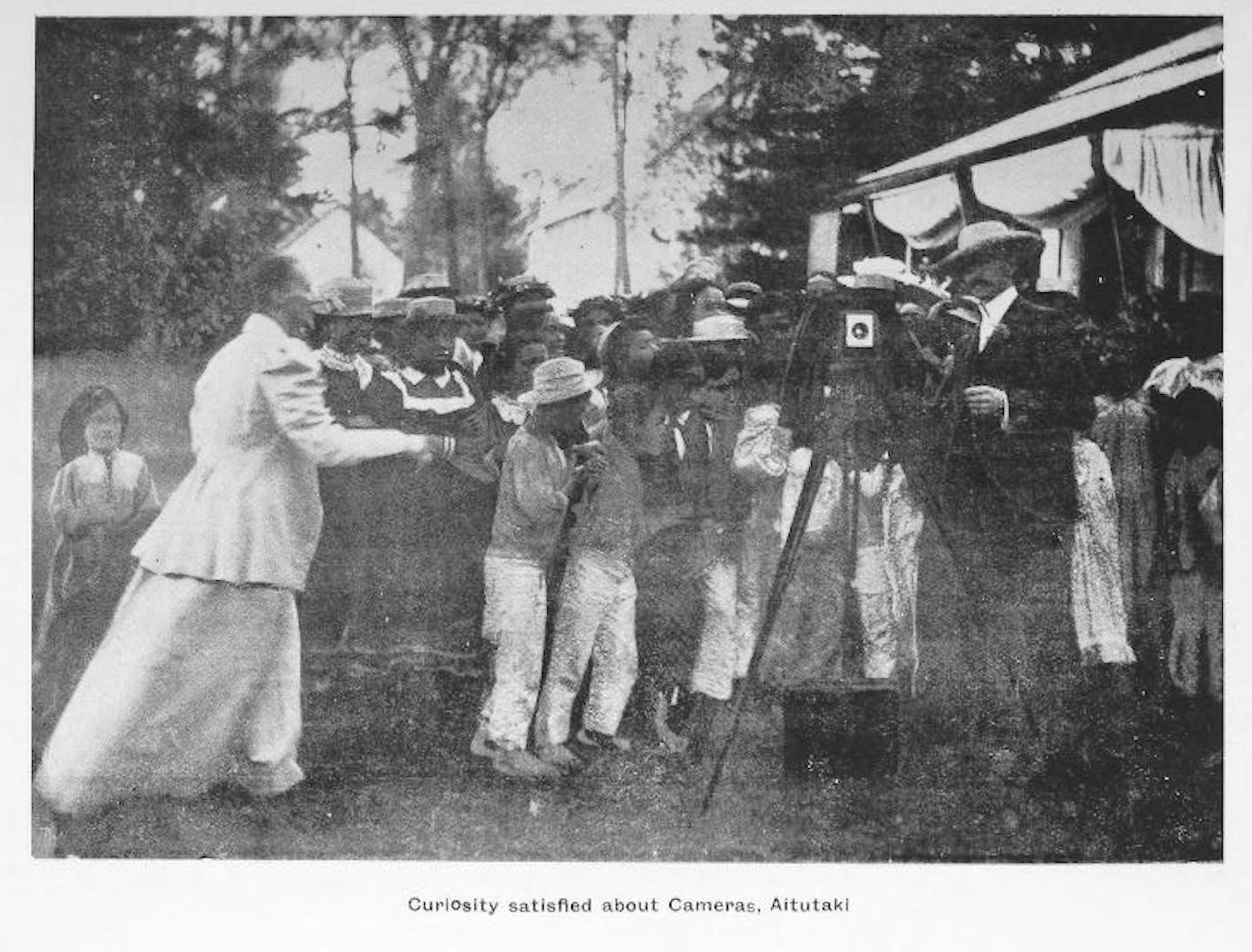

Curiosity satisfied about cameras in Aitutaki. 23080339

The problem was solved around the same time by an Englishman, William Henry Fox Talbot who invented the photographic negative, the reverse image being used to create duplicate photographic prints.

By the early 1840s “photography” had been commercialised with photographic studios operating in Europe and America.

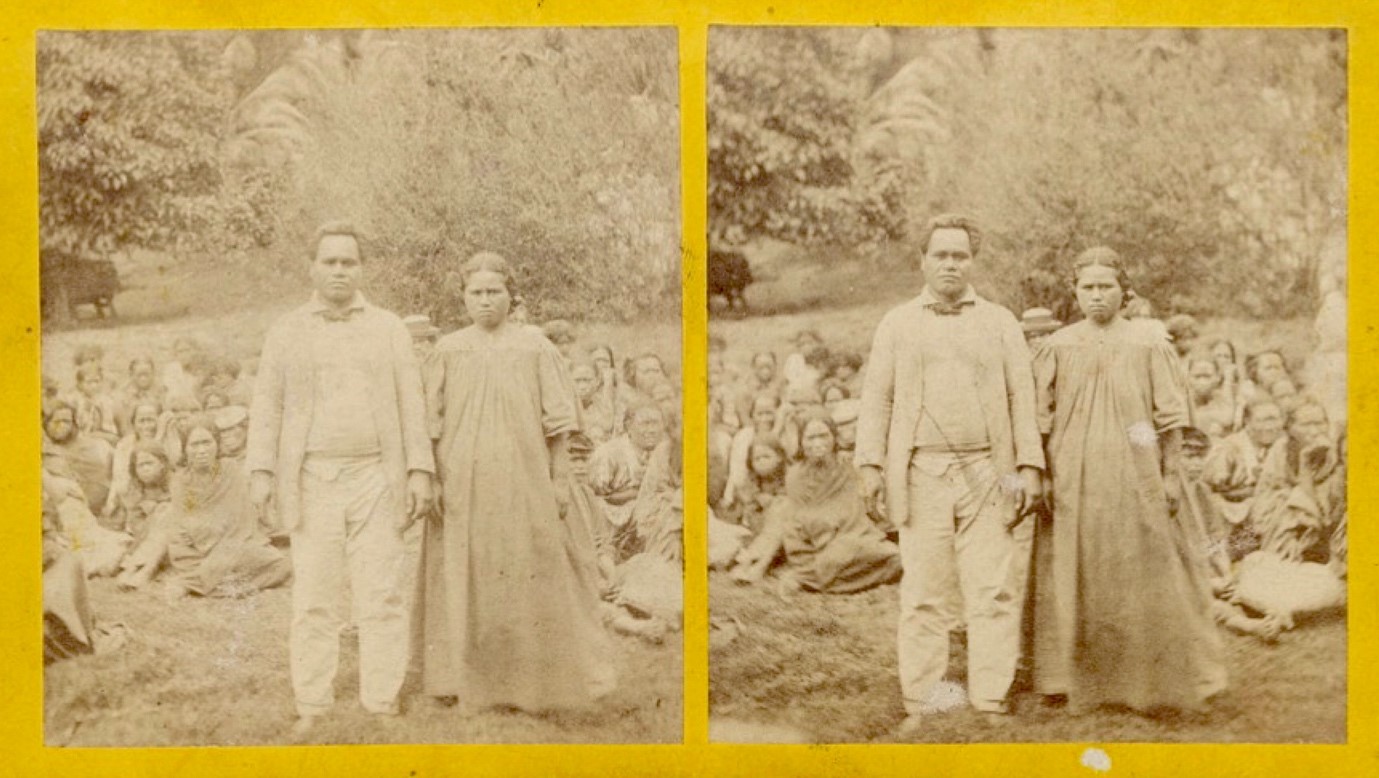

A couple believed to be orometua Sadaraka (Mamae) and his wife Aravao, ca. 1850s at Mangaia. Albumen prints, stereo card 83 x 172 mm. (Source: Michael Graham-Stewart and Francis McWhannell, ‘Jesus in the Pacific’ Missionary Exihibition, 2016, https://michaelgrahamstewart.com/jesus-in-the-pacific/)/23080340

The earliest surviving photograph taken in Australia was in 1841 and in New Zealand in 1848.

Prior to this, images were captured using the camera obscura, a device in existence since antiquity. A camera obscura (“dark room”) comprises a darkened box or room with a light source and small hole or lens at one side, through which an image is projected onto an opposing wall. The image produced is then traced onto paper or captured in some similar manner.

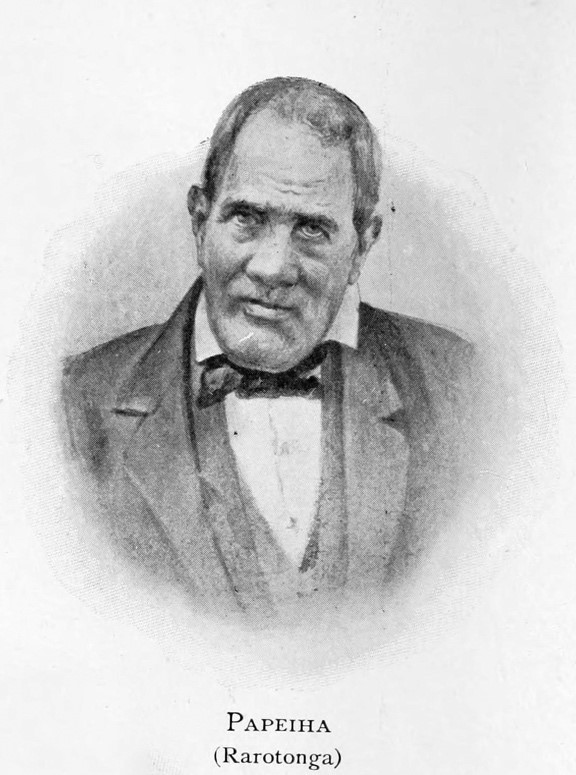

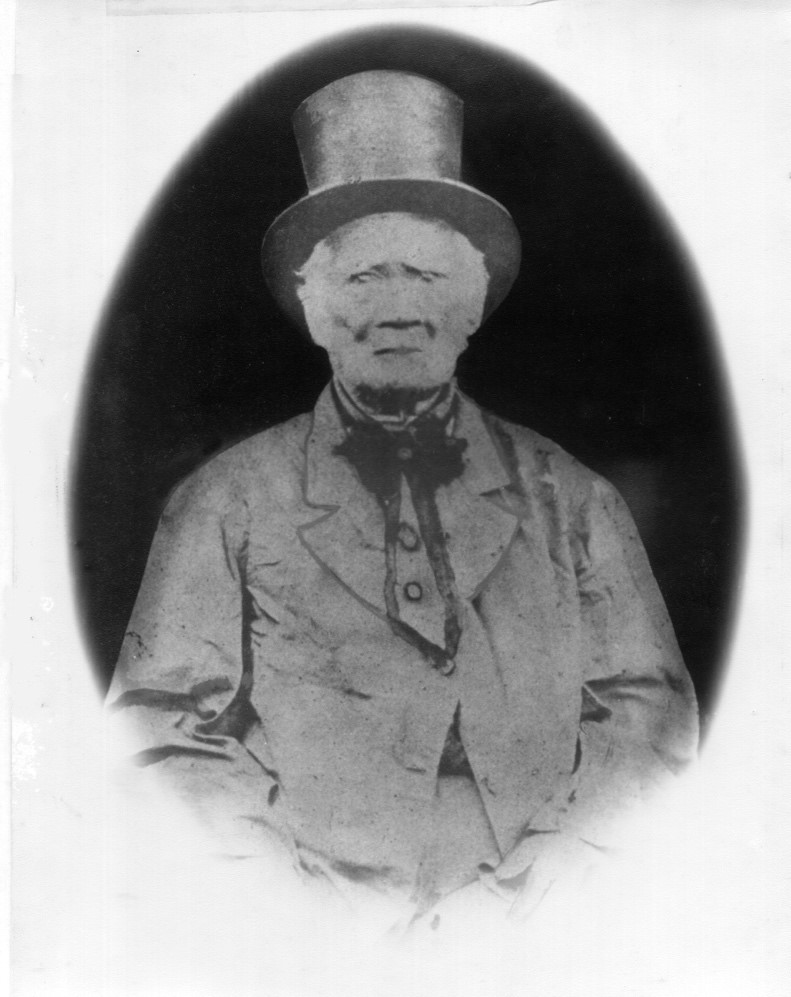

Image of Papeiha (Council for World Mission Archives, SOAS, London)/ 23080341

In the early 1830s the Reverend Aaron Buzacott built a camera obscura at Avarua, Rarotonga to capture images of Makea Pori Ariki and others. Buzacott records that “The views thus obtained were sent to Mr. Williams and were inserted in his narrative” Missionary Enterprises (1837). Buzacott’s camera obscura may have been the origin of the local word for camera - ‘ueata – “a container of shadows”.

An early photograph, believed to have been taken on Mangaia in the 1850s used the newly invented process to capture an image of the orometua Mamae, also known as Sadaraka or Koroa-iti and his wife Aravao, together with part of their congregation. Accurately dating this photograph is, however, problematic. A date around the 1850s would accord with the approximate age of Mamae as seen in this photograph – he was born in the early 1800s. On the other hand, the 1850s seem early for photography in the Cook Islands. The image is captured as a stereograph which creates a 3D image when viewed through a double-lensed viewer known as a stereoscope. Stereographs became popular in the 1860s.

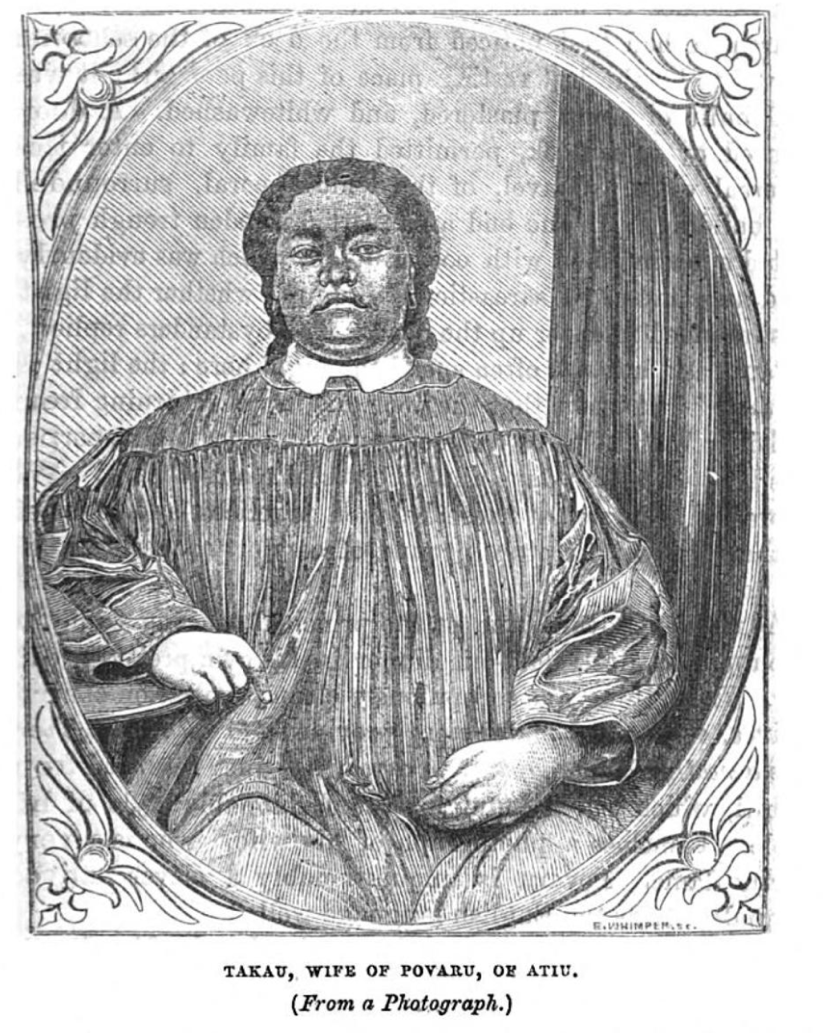

Engraving made from an original photograph. 23080342

A second photograph, again of an orometua, can be dated to the 1860s. It shows the evangelist Papeiha who brought the Gospel to Aitutaki (in 1821) and Rarotonga (in 1823). Papeiha died in 1867 and the photograph shows a man in early old age, suggesting the photo could have been taken early in the 1860s.

It is highly possible this image was taken by the Rev. E. R. W. Krause, resident missionary at Takamoa from 1859 – 1867.

On 30 December 1859 Krause wrote from Rarotonga to mission headquarters in London forwarding “photographic copies of scenery at Aneityum (Vanuatu) and a good likeness of myself. I hope to get one of my dear wife. I have also made some proofs of native teachers and their wives…” His photographic work was interrupted by delays in obtaining “maker” and “chemicals”. “I wish however, by and by, to get some good pictures for the [missionary] magazines.”

Numangatini ariki of Mangaia ca. 1872. (Photograph believed to be by Charles Edward Goodman or Rev. G. A Harris)/23080343

“Maker” possibly refers to the “fixing” agent that prevented photographic images from darkening when exposed to light.

A photographic image of Takau, the wife of Povaru of Atiu, a church deacon recently returned from ministering to Cook Islands workers in Tahiti, was likely taken during an outstation visit in 1869 by Rev James Chalmers and Rev. William Wyatt Gill. The original photograph, which has survived only as an engraving, appeared in the Juvenile Missionary Magazine, 1870. (At the time all photographs were rendered as engravings to allow them to be printed with ink on paper. Later in the century “half tone” technology made it possible to print photographs in newspapers, magazines, and books, at scale).

The earliest Cook Islands photographs that can be correctly dated were taken by Charles Edward Goodman who arrived in Rarotonga in 1870. Goodman’s father was a patron of the London Missionary Society and a friend of the Society’s Directors in London. He arrived with a letter of introduction to the Avarua mission.

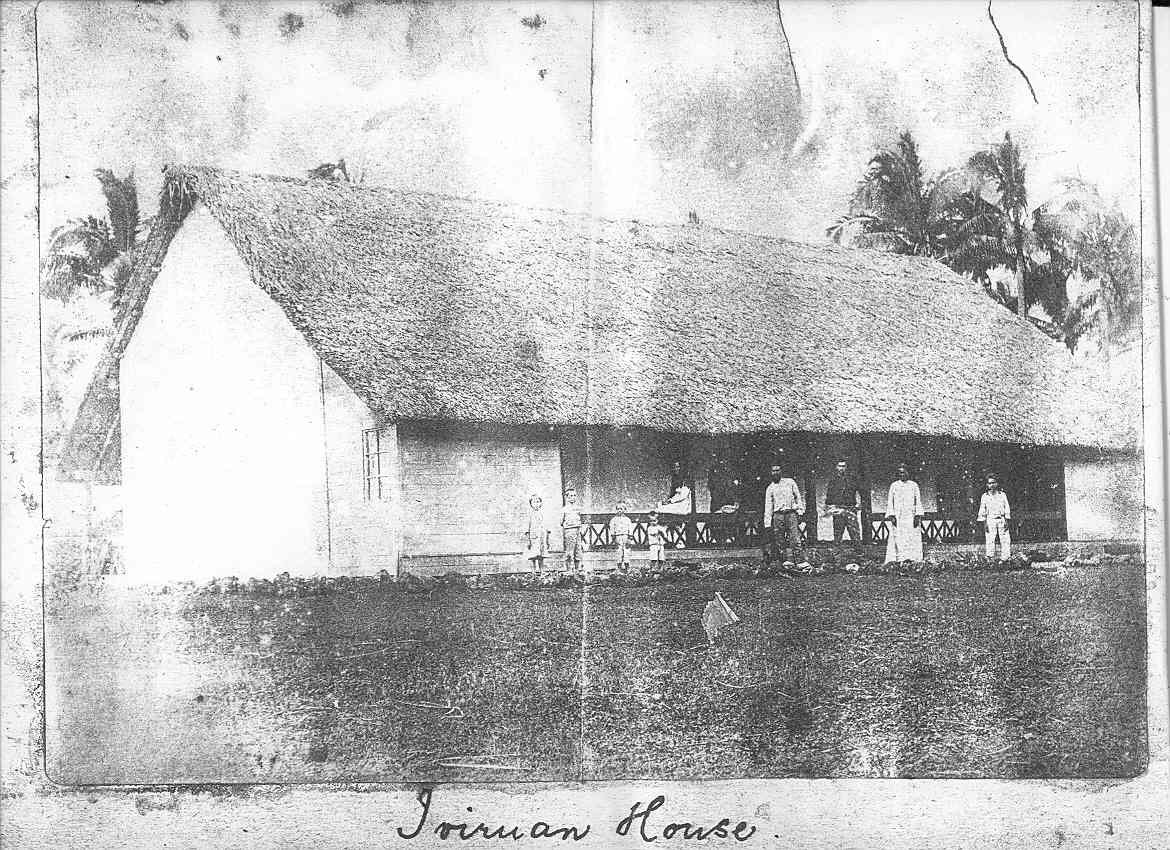

The pandanus thatched Ivirua Mission House built ca. 1870. (Photo - Bussanich Collection)/ 23080344

In August 1870 Goodman visited the outstations of the Cook Group “as an intelligent friend of Christian Missions desirous to trace the progress already made”.

On 14 October 1871 Goodman sent 10 photographs to the London Missionary Society headquarters in London showing:

- “No. 1. Maretu, the native pastor at Ngantangiia of whose goodness you have doubtless heard.

- No. 2 is his wife

- No. 3 Teava – late of Samoa [Rarotongan evangelist who accompanied Williams to Manono, Samoa in 1832, remaining as a missionary to Samoa until 1857]

- No. 4 Tepaeru ariki of world-wide fame [the relation of Makea taken to Aitutaki by the Cumberland in 1820 [1814] who helped introduce the Gospel to Rarotonga in 1823].

- No. 5 Manarangi (chief judge) and wife

- No. 6 Teaua and wife – native pastor at Avarua [possibly Teaia from Ngatangiia]

- No. 7 Ruatoka, supposed to be the oldest man in Rarotonga. The photo is so poor that it is hardly worth sending but I am not likely to get a better as he shakes very much on account of his great age.

- No. 8 and 9 are the king and his wife, Makea and Makea vaine.

- No. 10 a group of students. The view is the mission house at Avarua.”

In an accompanying letter, Goodman noted, “I will offer no apology for their many defects as I am but an amateur and the difficulties in the way of photography in a place of this land are many and great, even for one who thoroughly understand the subject … It is my intention to confine myself to views for the future on account of the great difficulty of getting a native to remain still for any time.”

The LMS Archives in London are currently not “sure what happened to these photographs and whether they were placed into the archive”.

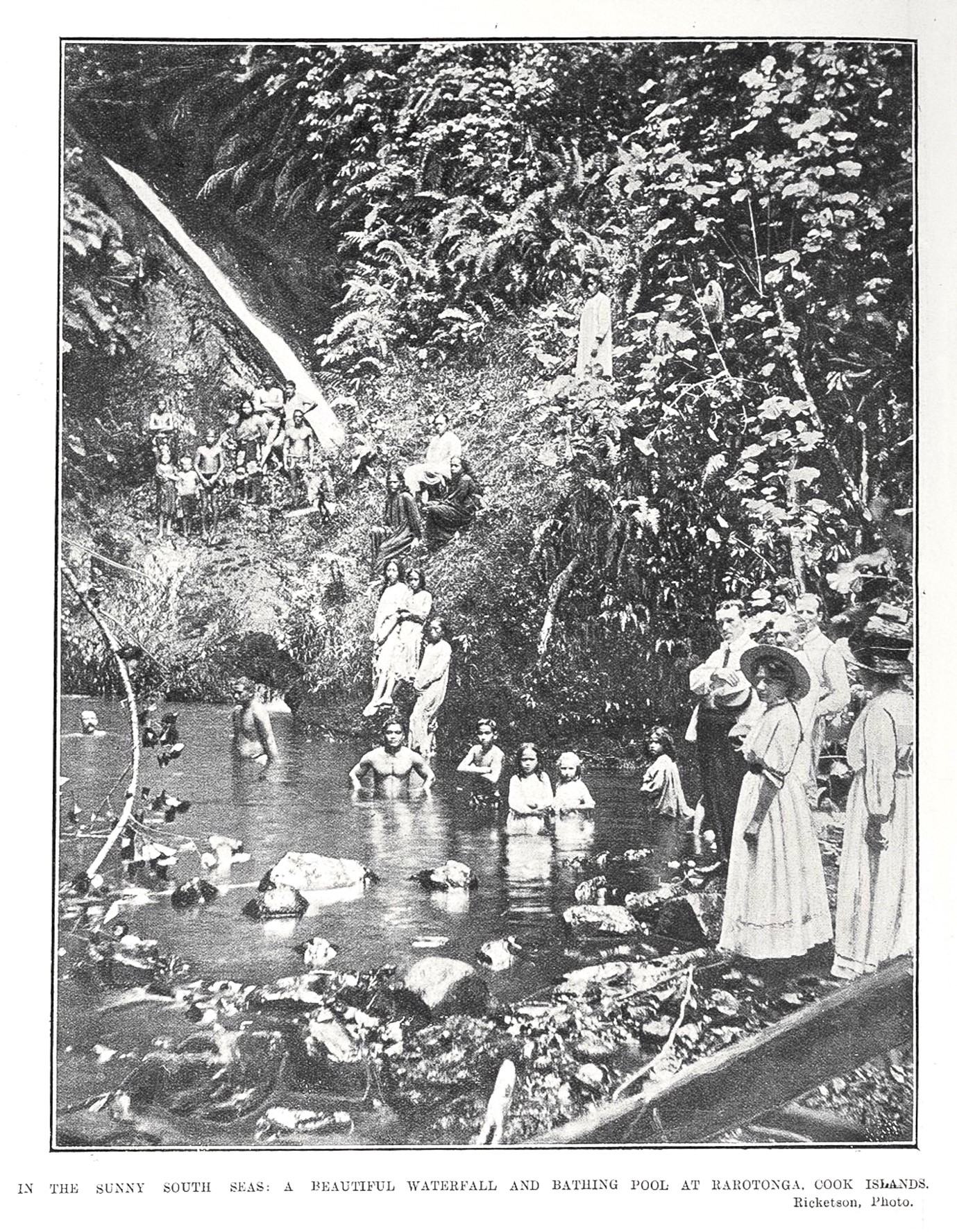

“Waterfall and Maoris bathing on W.G. Wigmores estate” (photo - Lucien Gauthier ca.1904)/ 23080346

In 1871 Goodman accompanied the head of the Rarotongan mission Rev. James Chalmers to Mangaia – “Mr. Goodman … is an amateur photographer and took a number of views. He succeeded in getting a few showing the mouth of the caves.”

It is probable that the photograph of the Mangaian ariki Numangatini was taken either by Goodman on this visit or perhaps by the resident missionary Rev. George Harris. Numangatini died in 1878 at an advanced age, one of the last links to pre-Christian Mangaia.

Goodman later established himself as a trader and agent for the insurance underwriters Lloyds of London and as “Her Majesty’s Vice Consul at Rarotonga”, appointed March 3, 1873. He married Te Tini a Maroka’a, otherwise known as Tini a Tui of Arorangi. They had three children - Ngapoko (f) Annie (f) and Te Ariki Upokotini Edward Goodman (m).

While initially a Church-going teetotaler, “Goodman’s career was not uncommon in the islands; he came as a healthy ‘young gentleman’ and left a drunkard and drug addict.”

He returned to London and following his premature death, his well-to-do English family sent for his Rarotongan children. Ngapoko and Anne travelled to England but young Edward refused and remained on Rarotonga. He married Te Pori Timona and subsequently Ngamata Tamaiva. He died without issue on 29 September 1951 at the age of 84.

The Reverend George Harris, stationed on Mangaia from 1871– 1893, was another amateur photographer. A number of early photographs survive in his family’s archive, including one of the Mission House at Ivirua, Mangaia, taken by Harris, possibly as early as 1871.

The beginning of the colonial era saw an inflow of newspaper photographers, official photographers, and professional photographers including the well-known Auckland photographer Henry Winkelmann, the celebrated French photographer Lucien Gauthier, and the Victorian photographer H. J. Ricketson.

Rarotonga obtained its own resident photographers George Robson Crummer (1868 - 1953) who arrived in Rarotonga in 1890; followed by the Englishman Sidney Hopkins (1878 – 1948). Hopkins’ downtown photographic studio was swept by waves up Takuvaine Road in the 1935 hurricane. They were followed by William ‘Bill’ Bond, Stewart Kingan, Henry Savage, Ron Powell, and the country’s first female professional photographer Marie Melvin. More recently Bob and Margot Johnson of Johnson's Photographic Studio and their son Bill Johnson and Lawrance Bailey helped Cook Islanders continue catching those disappearing shadows of the past.