‘Scurrilous rags’ and ‘brimstone belchers’ – Cook Islands’ early newspapers

Saturday 8 October 2022 | Written by Rod Dixon | Published in Features, Weekend

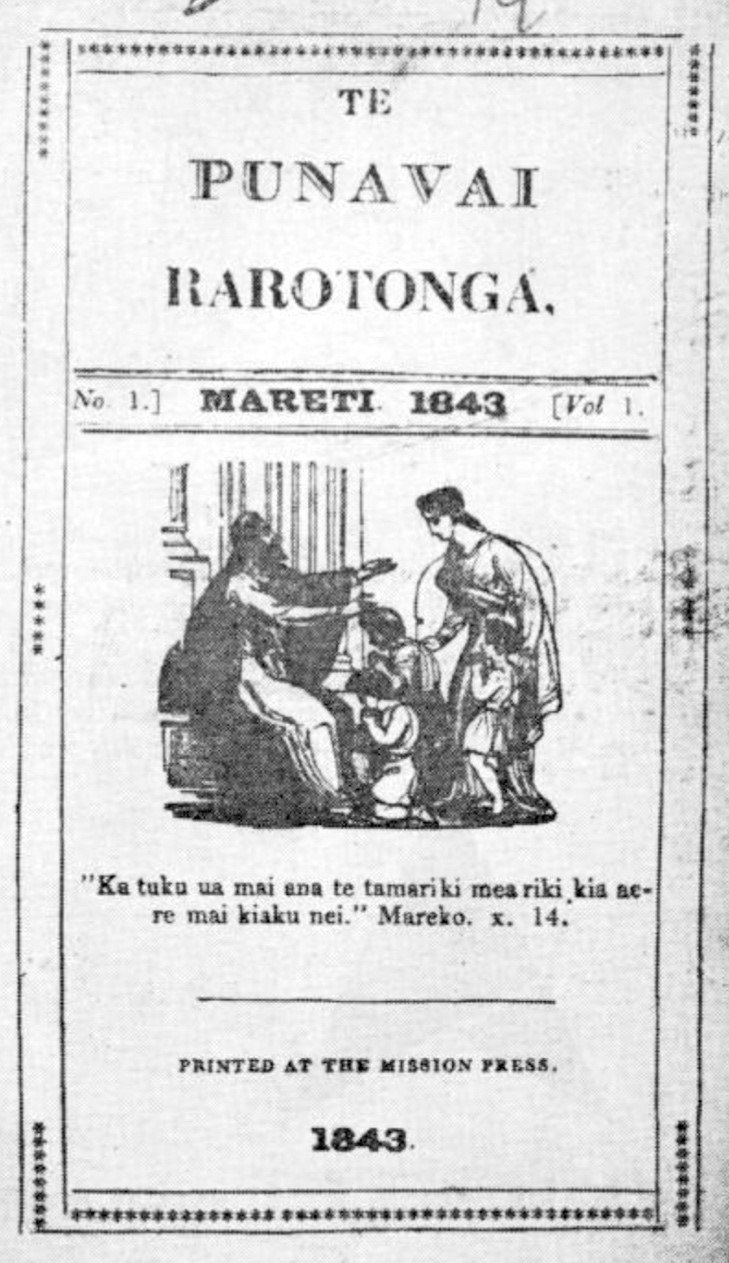

Rarotonga’s first newspaper – Te Puna Vai, Volume 1, Number 1, 1843. 22100714

An ‘insatiable lust’ for reading matter among Cook Islanders led to the appearance of Rarotonga’s first newspaper Te Punavai in 1843, printed with the help of the Sydney Morning Herald. Later in the century came Te Manu Rere, Te Torea and Ioi Karanga, all generating controversy and landing one local editor in prison – the first inmate of Rarotonga’s newest jail. By Rod Dixon.

Kai parau (Bible consumers) and ‘a’api parau’ (Bible learners) were the Tahitian derived names given to the early Cook Islands Christian converts. These names reflected what the Christian missionaries described as Cook Islanders “insatiable lust for books”, initially the Holy Bible.

In the days before literacy became widespread, scriptural tracts, which the Rarotongan missionary Maretu called ‘tia’, were “considered to have magical properties”.

“The letters made us wonder … and we said that the books were the gods of the strangers.”

Initially all scriptures and teaching were in the Tahitian language but, recognising that “a religious impression” was best achieved by addressing people in their mother tongue, John Williams developed a lexicon and grammar for the Rarotongan language in 1828.

Literacy spread quickly through the mission schools. Demand for school places outstripped supply and a decision was made to focus literacy on the young while encouraging older converts to apply their well-developed powers of memory to learn entire chunks of the Bible.

Joe Gray in his History of Rarotonga records “a chief of Ngatangiia (who) had memorised … all of the Epistles of John, then chapters of the Acts of the Apostles, the first chapter of John’s Gospel and a portion of Galatians (Pitman, 2 July and 17 August 1830), while a young Rarotongan woman could repeat the entire New Testament from memory”. (Pitman 21 November, 1842).

New-found literacy created a demand for more and more books in the local language. Initially, the books of the New Testament and a number of religious tracts were translated into Rarotongan by John Williams, Aaron Buzacott and Charles Pitman and were printed either at the mission press at Huahine or in London.

In 1831, Buzacott received a second-hand printing press from the Tahitian mission – the “old worm-eaten wooden one” with “an equally old fount of letter” (Buzacott, 1866; 68). He used this to create the first book ever printed on Rarotonga – Browne’s Catechism – in Cook Islands Māori.

Buzacott subsequently trained a young Rarotongan convert (identified only as “an intelligent native”) as his printing assistant. In his first year, with a very inadequate printing machine and limited fount, this young man succeeded in printing copies of a book of twenty-five hymns and two short religious tracts.

At the same time, Buzacott was building “a very commodious and substantial stone printing office” at Takamoa. According to the Rev. William Gill it was the first stone building ever built in Avarua – on the site of what is now the Takamoa Women’s Centre.

In 1839, with the arrival of a new printing press and a new fount of type, a substantial printing operation began at Takamoa, assisted by “several native lads” who quickly “became proficient workmen.” Two or three of these assistants – whom William Gill (1856; 51) describes as “men …. whose fathers knew no letter or sign to represent the words of their unwritten language” – received advanced instruction in printing from the Mission Press in Samoa.

As well as printing thousands of copies of books and pamphlets, the Takamoa press began to publish a monthly periodical – Rarotonga’s first newspaper - Te Punavai - “with a view to the improvement of the inhabitants of this group generally and especially the young.”

The periodical was written in Cook Islands Māori and the first copy was issued in March, 1843, with Buzacott as editor.

“The periodical is to contain various notices on Theology, History (Sacred and Profane), Natural philosophy and is to be distributed gratis (free) among our schools and Church members hoping thereby to excite a desire after knowledge and by the divine blessing, to secure the higher objectives of their spiritual welfare” (William Gill, 28 July, 1843).

Between January and December, 1844, in addition to printing one million pages of the books of Samuel and Judges, a quarter million pages of Kings, nearly a million pages of Roland Hill’s Catechisms, and primers in Geography and Arithmetic, the Takamoa press printed 36,000 pages of Te Punavai. Buzacott estimates that, in total, 3600 copies of the periodical were printed – the first in March, 1843, and the last in December, 1844.

The March and June, 1843 issues of Te Punavai contained parts I and II of a thirteen page report written by Ta’unga (one of the Rarotongan language’s most prolific writers), entitled ‘Te Aerenga o Barakoti ma i te kave aere i nga Orometua Rarotonga e te tutaka aere i te au enua etene, te rai i tataia e Ta’unga’ (The Trip of Buzacott and Others to Take Rarotongan Teachers and to Inspect the Heathen Islands, Mostly Written by Ta’unga).

The issue for March, 1844 published a census of Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia and Ngaputoru (Coppell, PIM, 1971).

“The price per copy” according to the Daily Southern Cross, (18 November 1870), was “more frequently counted at so many cocoanuts than anything else.”

The greatly increased output of the Takamoa printing office, after 1843, was made possible by finally “having a good printing press”, a large amount of paper supplied by the British Foreign and Bible Society and two new sets of founts donated by Messrs Kemp and Fairfax of Sydney, NSW.

Kemp and Fairfax were, at the time, the publishers of the Sydney Herald which in 1842, under the joint ownership of John Fairfax and his son Charles, became the Sydney Morning Herald.

The last edition of Te Punavai appeared in December, 1844.

Following the closure of Te Punavai, the idea of a local newspaper lay dormant until the arrival of the Rev. James Chalmers (“Tamate’) in May 1867. In 1870 Chalmers used the Takamoa press to publish Te Manu Rere, a news sheet offering four pages of news and reports on a monthly basis.

Chalmers believed that “priestly power is hateful” and sought to reduce the power of European missionaries over the Cook Islands church. (Chalmers, 9 May 1873). To that end, he encouraged Cook Islanders to take more responsibility for their affairs, both spiritual and secular.

He was also concerned that Cook Islanders were, by definition, insular and largely unaware of major external forces encroaching upon them.

Accordingly, “we have felt it desirable”, he wrote, “to interest the natives in what was taking place outside of our island…. So we have begun a monthly newspaper of four pages. It contains short articles on the subjects that happen to be uppermost at the time, shipping news, news from other islands, pieces culled from newspapers, and books, letters from natives, articles on history and also small pieces of scripture. The natives are much interested in it and look out for the first of the month when it is issued” (Lovett, 1902; 96-7).

One issue of Te Manu Rere carried a report of a battle then occurring in the Franco-Prussian War (1870– 1871). This led a local speaker at a Church meeting in support of sending Cook Islands’ orometua to New Guinea, to wonder aloud – “The missionaries taught us that fighting was bad, but we find that those nations which are called civilised still believe in fighting … I propose that we should send teachers to France and to Prussia” (Lovett,1902; 273).

It was thinking such as this that Chalmers hoped to inspire through Te Manu Rere.

But parochialism proved a stronger force. Early in 1873, Te Mau Rere published a letter from the Chiefs of Atiu asserting their ownership over Manuae, which, at the time, was claimed “by a worthless foreigner” (Chalmers, 9 May 1873). The Atiuan claim provoked talk of war in Aitutaki leading the orometua there, Rev. Henry Royle to warn his superiors in London that Chalmers’ newspaper risked fomenting violence through the airing of land disputes that were no business of the Church.

Chalmers was repentant and closed down the newspaper. “I now feel it would have been better not to have done this ... The Mission Press has not, with the exception of that one occasion, been used for political discussions and it will not be used for such purposes.” It was wiser, he concluded, to “desist from publishing it because of the many other duties now devolving upon me” (Chalmers, 9 May 1873). Te Manu Rere ceased publication in 1873.

There would be no regular newspaper on Rarotonga for another twenty-two years, until, on 26 January, 1895, a new four to six page bilingual weekly news sheet, called Te Torea, was launched by the British Resident F J Moss. The first edition declared that Te Torea will “tell the news and give the people the opportunity of exchanging ideas on all public affairs. Our motto will be “Do unto others as you would that they should do unto you.’”

Te Torea focussed on local and world news, with a letters’ column, social news, local laws, official government announcements and commercial advertisements.

A few months after appearing in stencilled format, Moss obtained approval from the Cook Islands parliament to purchase a small printing press for £50 with a view to Te Torea operating both as a newspaper and official Government printer. The press was rented to the Māori trader Henry Nicholas with an option to buy. Nicholas, in turn, imported a professional printer from Auckland and on 13 July,1895 the first printed edition of the paper appeared.

Moss helped Nicholas to edit (and censor) the paper which, consequently, had a strong pro-government bias. Later a Mr. H. Ellis became editor. At least one edition – for Saturday 21 December, 1895 – was, interestingly, printed on tapa cloth.

The Grey River Argus, (16 September 1896), noted that Te Torea “contains a respectable show of business advertisements (and) serves to indicate how thoroughly these Islands have awakened from the sleep of ages and entered upon a new phase of existence”.

The newspaper operated from 1895 – 1899, its fortunes declining as Moss came into growing conflict with local European traders and the Rarotongan ariki. As the conflict grew, Moss’ opponents withdrew their subscriptions and advertisements, claiming that “the British Resident has, by his own writings in the editorial columns of the Torea newspaper publicly misrepresented the true state of affairs at Rarotonga … ; … (and) used the editorial columns of the said newspaper without indicating that the writing was (his, and) not that of the editorial staff ...”

On 6 November, 1897, the paper announced “with extreme regret … that with the present issue, Te Torea will cease to exist … for some time Te Torea has not been a paying concern.”

The printing press was locked away for safe keeping in a shed owned by Henry Nicholas.

On November 20, 1897 the paper reappeared in its original cyclostyled

handwritten form: “We find, however, so unanimous a wish that the paper be continued that we have decided to accede to the wishes of our friends and relaunch the little bird upon the sea of journalism.” Te Torea continued in cyclostyled form until it closed on 21 February, 1899.

The printing press, meantime, had been claimed by Makea on behalf of the Federal Government. As Moss’ successor, Lt. Col., Gudgeon noted – “When … the Māori chiefs realised that they were being reviled by their own printing press, they endeavoured to obtain possession of that which they had reason to believe was their own property” (AJHR, 1890).

Moss refused to surrender it, and on 17 January, 1898, Te Torea’s former printer, Oscar Owen, accompanied by seven strong Rarotongans, led by Pora and Piaputa, forcibly seized the press from Henry Nicholas’ shed. During the struggle Owen assaulted Nicholas. The subsequent court case found Owen guilty of forcible entry, fined him £10 and bound him over to keep the peace for 12 months.

Owen, meanwhile, used the forcibly acquired printing press to publish a rival newspaper, Ioi Karanga, which, in its first issue on 19 January,1898,advised its readers its intention to be political in nature – “for a long time past it has been keenly felt that the establishment of an impartial and independent journal has become a real necessity in Rarotonga. Ioi Karanga claims to be able to supply that desideratum. As our name implies “We repeat what we hear.” But Ioi Karanga was neither impartial nor independent being instead a voice for Moss’ opponents in the European community.

The two papers feuded throughout 1898 and early 1899. Ioi Karanga described Te Torea “as a scurrilous and ownerless rag” while Ioi Karanga was, in turn, “a belligerent little newspaper belching forth brimstone against its contemporary” (PIM, 25 August, 1937).

The feuding ended up in court, with H. Ellis of Te Torea suing Oscar Owen of Ioi Karanga for libel.

The court found in favour of Ellis. But a few months later, in March 1899, finding his profits insufficient to pay his legal costs, Ellis was sentenced to 14 days in prison for contempt of court – a newspaper editor becoming the first occupant of the new Rarotonga jail. Te Torea ceased publication a month earlier, on 21 February, 1899.

In February 1899 Stephen Savage became the new ‘manager’ of Ioi Karanga, now, effectively, a government newspaper. But, as Bill Coppel reports - “Ioi Karanga did not long survive its rival,” despite receiving a £15 a year subsidy from the Federal government (AJHR, 1899).

With annexation in 1901, Gudgeon became New Zealand’s Resident Commissioner to the Cook Islands and, intolerant of journalists questioning his decisions, announced that – “In order to economise, I have discontinued the Ioi Karanga newspaper and taken Mr. Savage, the printer, as my secretary.”

The paper ceased publication on 27 July, 1901. It was replaced by the official Cook Islands Government Gazette with Savage assuming the role of Government Printer.

In 1900 it was reported that Henry Nicholas was planning to revive Te Torea but the project foundered for want of funding. Nicholas died the following year. ‘Independent’ printing and publishing in the Cook Islands now reverted to the Mission press. The new missionary to Mangaia, Rev. James Cullen, had a background in printing, and relocated the mission press from Takamoa to Mangaia, together with an experienced Niuean printer called Pamatautau.

Pamatautau trained Mangaian students, who were preparing for entry to Takamoa, to set up and print at the rate of 16 pages per student per week. In addition to printing Māori language Christian texts, the Mangaia mission press began, in late 1897, to publish a monthly newsletter, called the Fugitive Papers (‘fugitive” referring to topics of passing interest, or ephemera).

The intention of the newsletter was, in Cullen’s words, to “enlarge the minds of the natives … and … help them in the study of the Bible.” The paper started out as an eight page, then twelve, then sixteen-page news sheet. By 1900, renamed Te Karere, it comprised twenty pages with a total circulation estimated at 6000 and distribution in the northern and southern Cook Islands, Tahiti, Raiatea, Niue, Samoa and the New Guinea coast. It continued to be published until 1934.

Two years later, in 1936, the first indigenous Cook Islands-owned and published newspaper Te Akatuaira appeared, edited by Albert Henry.

Te Akatauira’a masthead read – Ko te otu teia i arataki ia mai i to tatou ai tupuna i mautanga ana, kia riro katoa teia ei arataki ia kotou ki te marama o te tupu nei i teia tuatau. (This is the star that guides and gives reflection from our ancestors that will lead us to light and knowledge).

Te Akatauira started off as a weekly and became a daily in 1939. According to Albert Henry’s biographer, Kathleen Hancock, “The newspaper did not contain much news at first – it survived on its classified advertisements and occasional reports of a football match or club meeting. Now and then, Albert would print one of his ‘stories’ to liven things up a bit. He wrote the paper, typed it, and duplicated it, helped by his eldest boy Tupui. His wife Elizabeth, an expert machinist, would sew the pages together on her trusty treadle machine. Te Akatauira sold like hot cakes – it was written in Māori and it was the Cook Islanders own news sheet.”

In the years preceding World War II, Dick Scott records, “Henry reported Nazi attacks on Jews and Japanese atrocities in China and opposed the policy of appeasement accepted by the Empire’s rather more grand newspapers. The German behaviour was “very bad and the Jews were innocent,” Henry wrote, “… why can’t someone come up and slap Germany’s ears.”

While the British media were celebrating the Munich Agreement and ‘peace in our time’, Albert Henry was warning “that Nazi Germany would not be appeased. ‘Trouble is brewing in Europe,’ he wrote in 1938. “Very soon we’ll have war” (Scott; 1991; 218).

When war finally broke out in 1939, Te Akatauira published the latest uncensored reports of the war’s progress from broadcasts picked up on Rarotonga from a downtown Los Angeles radio station. “Such unofficial information was unwelcome, Henry’s independent reporting was not appreciated; denied adequate paper supplies, and harassed by censorship, he had to close the paper down. In October 1942, the Henry family migrated to New Zealand” (Scott, 1991;225).

Te Akatauira was resurrected in 1956 in New Zealand and helped provide momentum towards Cook Islands self-government. It also provided Henry with the media skills he later combined with his natural charismatic and oratorical gifts to become one of a long line of former journalists who became Prime Ministers of their countries.

References

Aaron Buzacott, 1866, Mission Life in the Southern Islands, J. Snow & Company, London

W. G. Coppell, 1971, “Cook Islands history is buried in its lost newspapers”, in Pacific Islands Monthly, 1 March.

W. G. Coppell, 1974, When newspapers waged war in the Cooks, in Pacific Islands Monthly, 31 January

William Gill, 1856, Gems from the Coral Islands, Ward and Co., London

Joe Gray, 1975, History of Rarotonga, PhD thesis University of Otago

Richard Lovett, 1902, James Chalmers His Autobiography and Letters, Religious Tract Society, London

Dick Scott, 1991, Years of the Pooh-bah, Hodder and Stoughton, Auckland.